ANNEX: July 2025 Report from Team Zamzam Counselors

The current humanitarian situation of those who fled from Zamzam to Tine from April 2025 until the writing this report (July 18, 2025):

After a stifling siege that exceeded a year, on. the 14th of April 2025, the RSF militias violently and viciously attacked Zamzam IDP camp southwest of El Fasher city, killing several hundred IDPs, injuring many, raping, burning, looting, and razing to the grounds the entire camp of over half a million civilians. This barbaric attack forced the entire camp population to flee in panic and in different directions.

The attack forced many IDPs to flee to northwards to the city of El Fasher, while others fled westwards to the town of Tawila, located about sixty kilometres from Zamzam. In the aftermath of the attack, many lives were lost and several hundred people are still missing; those who managed to escape the attack went to Tawila town which was already filled and overcrowded by displaced people. Many, and especially those who had family members to help them, have continued their arduous journey to Tiné (Djabaraba), Chad.

In addition to those people still missing people, the attack on Zamzam camp left hundreds of people dead due to dehydration and the required long-distance walking. Exhaustion among the elderly and sickness caused many deaths. Two weeks after fleeing the hell of the Zamzam attack, more than half of the Zamzam camp residents had gathered in Tawila town, 60 kilometers west of El Fasher city; but the humanitarian and security situation wasn’t stable in this town, which is under the authority of Abdul Wahid al-Nur as well as other militias allied with the RSF—this despite a considerable presence of International Nongovernmental Organizations (INGOs).

The humanitarian conditions in the town of Tawila are bleak; and it lies only some fifteen kilometres from the range of RSF guns firing from nearby. We also found that the existing camps in the Tawila area were badly overcrowded; moreover, there was insufficient humanitarian aid as well as a sense of animosity, an unwelcoming spirit of animosity on the part of the various militias who are charge of this area [these are the forces largely loyal to former Darfur rebel leader Abdel Wahid al-Nur, who is of the Fur tribe; there is historic enmity between the Fur and the Zaghawa, the tribal group from which most of Team Zamzam has been drawn—ER]. These factors discouraged many new arrivals who thought of settling down but decided instead to continue westward toward Chadian territory.

The distance between Tawila and Tiné on the Sudan-Chad border does not exceed 250 kilometres, but with the presence of so many checkpoints set up over this distance—about 50—the distance was daunting. The checkpoints—locations demanding money or goods—were manned by either the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) or their affiliated Arab militias; this “asset stripping” has made it impossible for many impoverished families to leave Tawila. For at each checkpoint, to be allowed to pass through, fees must be paid by the traveler, whether they adult or children; by time one reaches Tiné it has cost about $100 per person.

Because of these hardships—including humiliation and intimidation at checkpoints and the need to travel thorough rough roads controlled by armed maniacs—those who have family members abroad have needed their help to make it to Tiné. And still waves of people arrive in Tiné on daily basis and will continue to do so if heavy rains don’t temporarily halt their travel. Tiné Jagraba on the Sudan-Chad border is located about three hundred kilometres from Zamzam camp, which has been home for more than fifteen years for many displaced people. It is not the last stop for us, nor an ideal sanctuary ; but for the meantime, we are far away from constant terror of RSF and militia violence.

In eastern Chad, there are about 14 camps for Sudanese refugees who fled the hell and genocidal wars begun by the former regime of Omar al-Bashir. With the help of the Janjaweed militias—which later turned into the RSF now fighting the Sudanese army—the killing and massacres of unarmed citizens forced almost three million people to become internally displaced or refugees in Chad. But there was not a single refugee camp in a Tiné town until the displacement of the people of Zamzam camp in 2025. The waves of refugees fleeing the recent attack on Zamzam has taken the local authority and inhabitants of this town Tiné by surprise. Nonetheless, they have not hesitated to help as much as possible, providing minimal shelter and other assistance.

In addition to local support from local charities and residents, some United Nations organisations began to come, but they brought only an absurdly small food aid. And it is still the case that most of the refugees are scattered in the open air with the heavy rainy season already having begun. The aid provided to the refugees pouring into Tiné since end of April is very small and the pace of transferring these refugees from Tiné to other camps in eastern Chad is terribly slow, and this is creating frustration and despair among refugees.

Other Accomplishments by Team Zamzam in Reconstituting Itself

• The Team has secured a large communal living space for themselves and their families;

• They have established excellent relations with the local authorities in Tiné and have traveled to the capital of Chad (N’Djamena) to explain their mission in Tiné

• They have made a number of key purchases:

A small solar generator

3 telephones to communicate within the area and with Gaffar

Cooking utensils and serving plates and bowls

• They have also purchased:

12 tents

Numerous mattresses/blankets/sleeping covers

Very substantial quantities of food

(one notable difference between Zamzam and Tiné is the price of food, which is greatly reduced, as Tiné functions as something of a region trading center, for food, materials, and other commodities)

Testimonials from some of the victims of sexual violence:

[1] Qasma Abakar Abdulrahman 34-yeah-old, widow and mother of six, said :

“My two daughters, one fourteen years old and the youngest twelve, were beaten and raped in front of my eyes during an attack on Zamzam camp.” She said further : “I tried to save them but the RSF threatened to shoot me. But even this didn’t stoped me from trying. They hit me on the head with an iron bar to knock me down and then tied me up. And while they were doing their dirty stuff on my daughters [references to sexual violence by culturally consservative non-Arab Darfuris are invariably euphemistic—ER], I heard their superior giving them orders to go search house by house and not to leave any girl belonging to the Fur and the Zagahawa.”

The two victims have received intensive counselling from Team Zamzam and are making good progress. Their mother thanked the counsellors for helping them.

[2] Ahlam Siddiq Mustafa, 16 years old, said:

“The Janjaweed [RSF] caught me with my mother, two women relatives, and three girls from my neighbourhood while fleeing the Zamzam attack. They then took us to an unknown location. There, they took everything from us, even our shoes, and they began to ask us for money or to call our relatives to send money for our release. They held us for six days without food or clean water before letting us go to Tawila. We were about eight young girls but nobody was spared from humiliation [sexual assault—ER] and beaten. After seeing my sisters of Team Zamzam several times, I now feel a lot better. But some of my friends are still suffering from stress and pain ; one of them got pregnant and she is suffering too much.”

************

Most relevant recent news/organizational reports concerning the fate of humanitarian work in Sudan (see in particular the extraordinarily full–and damning–reporting by The Washington Post: #6)

[1] UNHCR Suspends Some Activities in Eastern Chad

Adre, July 3(Darfur24)

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) announced in a statement that it will reduce its offices and suspend some humanitarian activities in eastern Chad due to weak and limited funding. The statement explained that the decision stems from insufficient funds to continue providing services to Sudanese refugees and host communities in the region.

The statement indicated that the UNHCR will reduce the number of its offices and suspend some humanitarian activities in eastern Chad, which will impact the provision of basic services.

These measures are expected to impact health, education, and protection services provided by the UNHCR to Sudanese refugees crowded into eastern Chad. The UNHCR stated that it will work to increase funding and ensure the continuity of services to refugees in eastern Chad, in coordination with local and international partners to prioritize and deliver essential services to refugees.

Since the war began in Sudan in April 2023, more than 844,000 Sudanese refugees have crossed into Chad, which was already hosting nearly 409,000 Sudanese fleeing previous waves of conflict in Darfur since 2003, according to the United Nations.

[2] A lengthy photographic dispatch from The Atlantic (Darfur/Tiné, eastern Chad)

https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2025/05/humanitarian-disaster-sudan-chad/682758/

[3] Refugees escaping Sudan face escalating hunger and malnutrition as food aid risks major reductions

30 June 2025 | World Food Program

NAIROBI, Kenya – The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) today warned that millions of Sudanese refugees who have fled to neighbouring countries risk plunging deeper into hunger and malnutrition as critical funding shortages force drastic cuts to life saving food assistance. Since conflict erupted in Sudan in April 2023, more than 4 million people have fled to neighbouring countries in search of food, shelter and safety – with families often arriving traumatised, malnourished, and with little more than the clothes on their backs.

WFP quickly mobilized to provide emergency assistance to refugees escaping to seven neighbouring countries. Food and cash, hot meals, and nutrition support have been provided in the Central African Republic (CAR), Chad, Egypt, Ethiopia, Libya, South Sudan, and Uganda. The agency also expanded support to host communities who have generously welcomed refugees, despite often grappling with their own food insecurity needs.

However, continued food assistance is quickly exceeding available funding. WFP’s support to Sudanese refugees in CAR, Egypt, Ethiopia and Libya may grind to a halt in the coming months as resources run dry. In Uganda, many vulnerable refugees are surviving on less than 500 calories a day – less than a quarter of daily nutritional needs – as new arrivals push refugee support systems to the breaking point. And in Chad, which hosts almost a quarter of the four million refugees who fled Sudan, food rations will be reduced in the coming months unless new contributions are received soon.

“This is a full-blown regional crisis that’s playing out in countries that already have extreme levels of food insecurity and high levels of conflict,” said Shaun Hughes, WFP’s Emergency Coordinator for the Sudan Regional Crisis. “Millions of people who have fled Sudan depend wholly on support from WFP, but without additional funding we will be forced to make further cuts to food assistance. This will leave vulnerable families, and particularly children, at increasingly severe risk of hunger and malnutrition.”

Children are particularly vulnerable to sustained periods of food insecurity. Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) rates among refugee children in reception centres in Uganda and South Sudan have already breached emergency thresholds as refugees are severely malnourished even before arriving in bordering countries to receive emergency assistance.

Inside Sudan, WFP has worked to scale up assistance to reach over 4 million people per month – four times more than at the beginning of 2024. Vital support to new refugees in neighbouring countries was also expanded; in Chad, WFP quadrupled warehouse capacity and expanded food pipelines to support the influx of refugees crossing from Darfur and to sustain cross-border operations into Sudan. In Egypt and South Sudan, WFP scaled up cash assistance after the civil conflict began in 2023, enrolling eligible Sudanese families within hours of arrival to provide immediate support.

“Refugees from Sudan are fleeing for their lives and yet are being met with more hunger, despair, and limited resources on the other side of the border,” said Hughes. “Food assistance is a lifeline for vulnerable refugee families with nowhere else to turn.”

WFP is urging the international community to mobilise additional resources to sustain food and nutrition assistance for Sudan’s refugees and the host communities supporting them.

WFP needs just over US$200 million to sustain its emergency response for Sudanese refugees in neighbouring countries for the next 6 months. An additional $575 million is needed for life-saving operations for the most vulnerable inside Sudan.

“Ultimately, humanitarian support alone will not put an end to conflict and forced displacement –political and global diplomatic action is what’s urgently needed to end the fighting so that peace and stability can return,” said Hughes.

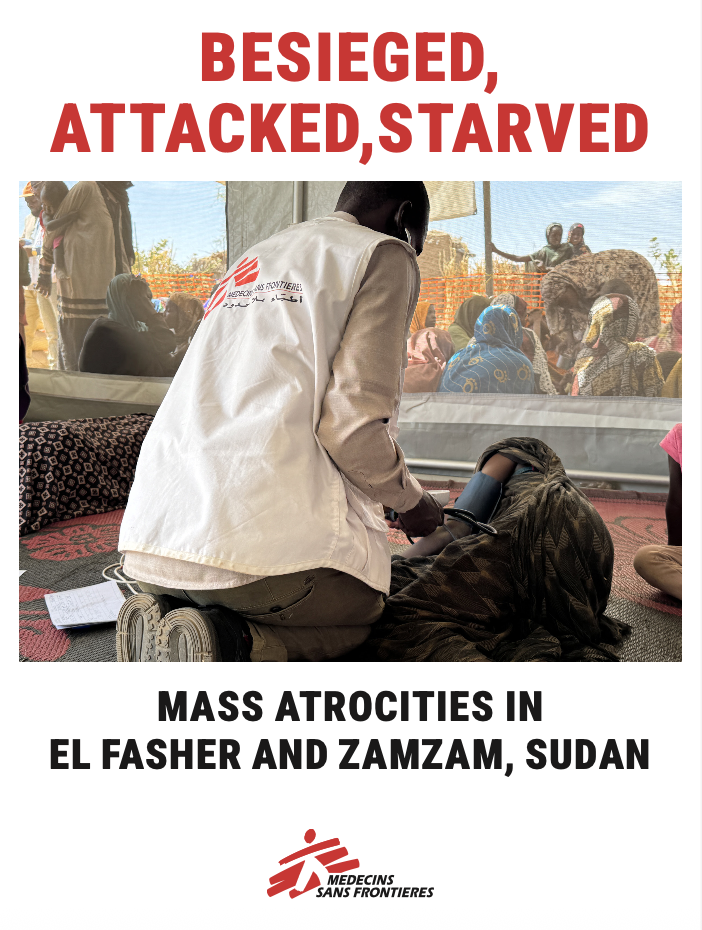

[4] Doctors Without Borders/ Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) | July 3, 2025 | https://www.msf.org/besieged-attacked-starved-mass-atrocities-el-fasher

Ever since fighting between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), supported by the Joint Forces, intensified in April and May 2024 in El Fasher, North Darfur, civilians have been caught in the crossfire. The warring parties have consistently and indiscriminately bombed areas where civilians live. Additionally, the RSF and their allies have systematically targeted non-Arab communities, and particularly the Zaghawa: the violence has included shelling, looting, mass killings, sexual violence, and abductions, and most-recently culminated in the assault on Zamzam camp for internally displaced people (IDP).

Access to healthcare has collapsed due to repeated attacks on medical facilities, and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been forced to cease activities in El Fasher and Zamzam camp. Non-Arab communities have been left without food, water, or medical care, contributing to the spread of famine. MSF warns of ongoing ethnic violence and calls on the warring parties and international actors, including United Nations (UN) agencies, to take urgent action to protect civilians, implement UN Security Council Resolution 2736, and launch a large-scale humanitarian response.

[5] IOM reports that about 406,300 people have been displaced from Zamzam camp, near El Fasher, North Darfur State between April 13 and May 2, 2025. OCHA, 2025, ‘SUDAN: Displacement from Zamzam camp, North Darfur State Flash Update No. 03’, Available here: Sudan: Displacement from Zamzam camp, North Darfur State – Flash Update No. 01 (As of 15 April 2025) | OCHA

[6] In Sudan, where children clung to life, doctors say USAID cuts have been fatal

The Trump administration’s cuts to USAID had an immediate and deadly impact in war-ravaged Sudan, according to civilians, doctors and aid officials.

WASHINGTON POST, June 29, 2025

QUAZ NAFISA, Sudan — The 3-year-old boy darted among the mourners, his giggles rising above the soft cadence of condolences. Women with somber faces and bright scarves hugged his weeping mother, patting her shoulders as she stooped to pick up her remaining son. Marwan didn’t yet know that his twin brother was dead.

Omran shouldn’t have died, doctors said. The physician at his clinic outside the Sudanese capital said basic antibiotics probably would have cured his chest infection. The International Rescue Committee, which received a large amount of its funding from the United States, had been scheduled to deliver the medicines in February. Then the new U.S. administration froze foreign aid programs, and a stop-work order came down from Washington.

Omran died at the end of May. As his health declined, his frantic mother had carried him in ever-widening circles to 11 health facilities. None had the medicine he needed.

“He was just in my arms whimpering, ‘I’m so sick, Mom,’” said 24-year-old Islam al Mubarak Ibrahim. “I was holding him and trying to comfort him, and I prayed to God to save him.”

Her boys were inseparable. Marwan thinks Omran is still in the hospital. “One day, I will just tell him, ‘Your brother went to Paradise,’” she said.

After more than two years of ferocious civil war, Sudan is home to the world’s largest humanitarian crisis, the United Nations says. Both sides have attacked hospitals. The military often delays or denies aid access; the paramilitary it is fighting has kidnapped relief workers and looted aid facilities.

Disease and famine are spreading unchecked. More than half the population, some 30 million people, need aid. More than 12 million have fled their homes. For so many families barely hanging on, programs funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) were a lifeline — providing food to the hungry and medical care for the sick.

While the Trump administration’s cuts to USAID this year have been felt deeply across the world, their impact in Sudan was especially deadly, according to more than two dozen Washington Post interviews with civilians, clinicians and aid officials in the capital, Khartoum, and surrounding villages.

When U.S.-supported soup kitchens were forced to close, babies starved quietly, their mothers said, while older siblings died begging for food. Funding stoppages meant that critical medical supplies were never delivered, doctors said. The lack of U.S.-funded disease response teams has made it harder to contain cholera outbreaks, which are claiming the lives of those already weakened by hunger.

The World Health Organization says an estimated 5 million Sudanese people may lose access to lifesaving health services as a result of the U.S. cuts.

In a response to questions from The Post, the State Department press office said it was “reorienting our foreign assistance programs to align directly with what is best for the United States. … We are continuing lifesaving programs and making strategic investments that strengthen other nations and our own country.”

“Americans are the most charitable and humanitarian-minded people in the world,” the statement continued. “It’s time for other countries to step up in providing lifesaving aid.”

For now, no one has filled the void left by Washington. European countries, including Germany, France and Britain, have also slashed funding for international relief or announced their intention to do so. Russia and China rarely fund humanitarian work; wealthy Persian Gulf countries tend to work outside established foreign aid systems. On the ground in Sudan, volunteers are appealing to members of the diaspora, many of whom lost their homes and savings when they fled the war.

As Tom Fletcher, a top U.N. relief coordinator, put it this month: “We have been forced into a triage of human survival

Empty shelves

The health center in Omran’s village of Quaz Nafisa, about 35 miles north of Khartoum, is supposed to serve 60,000 people, physician Amira El Sadig said, but its entire stock of medicines now fits on a single shelf of a filing cabinet, with room to spare.

Sadig, 41, was delighted last year when the International Rescue Committee announced it would provide the clinic with medications, solar panels to cool vaccines, oxygen tanks, simple medical devices, and lab tests for malaria and other diseases. A referrals system set up by the IRC would help patients needing more-specialized care.

When President Donald Trump took office in mid-January, he signed an executive order calling for an immediate freeze to foreign aid programs and vowing no further assistance “that is not fully aligned with the foreign policy of the President of the United States.”

In February, billionaire Elon Musk proclaimed that his newly created U.S. DOGE Service was “feeding USAID into the wood chipper.” Sweeping global cuts soon followed. As the fatal consequences became clear, and political backlash intensified, the administration said it would restore funding for essential, lifesaving programs. But in many places, including Sudan, vital staffers had already been fired and payment systems disabled, aid workers said.

Initially, the IRC project in Quaz Nafisa was frozen by the stop-work order. Then it was terminated on Feb. 27, the organization said. It was partly reactivated March 3, but the disbursement of funds was delayed. Five months later, the clinic is due to begin receiving the help it was promised at the beginning of the year.

Sadig listed a handful of what she said were preventable deaths between February, when the medications were due to arrive, and the end of May. They included a man with a scorpion bite. A woman with cholera. A diabetic who needed insulin. And Omran, the dimpled 3-year-old.

“There are other deaths in the villages around here that we don’t even know about,” Sadig said. “Most people don’t bother to come here because it is not equipped.” Sadig wishes that she could solve the problem with her “own hands,” that her country could stand on its own. “We say thank you to the American people for helping with our suffering,” she said.

When a U.S. stop-work order came in January, Fatma Swak Fadul said, almost all the soup kitchens in her neighborhood shut down overnight.

Kitchens closed

In the desert outside the city of Omdurman, just to the northwest of the capital, Fatma Swak Fadul lives in a sweltering adobe slum. She used to have seven children; now she has five.

For more than a year, they survived on a single daily meal from local soup kitchens. They were run by volunteers from the local Emergency Response Rooms, which formed in 2019 during the pro-democracy protests that helped topple military dictator Omar Hassan al-Bashir. The two years following his ouster were a heady era of hope, until two generals — the head of the military and the leader of the Rapid Support Forces paramilitary — joined forces to overthrow the fledgling government.

Two years later, their rivalry spilled into all-out war, and the young demonstrators mobilized again. They smuggled food and medicine across front lines and cooked provisions donated by charities in vast pots, trying to keep the hungriest alive.

Last year, USAID gave the Emergency Response Rooms $12 million, which accounted for 77 percent of the soup kitchens’ funding, said Mohamed Elobaid, who manages the group’s finances. When the stop-work order came in January, Fadul said, almost all the soup kitchens in her neighborhood shut down overnight. So her children starved. Her daughter Nada, only 18 months old, starved to death in February, she said, and was often too weak to cry. Three-year-old Omer, who loved to wrestle with his siblings and dreamed of owning a bike, lingered longer. First, his mother said, he began to lose his vision, which can be a side effect of malnutrition. Then he began asking fretfully for an absent brother. In his last days in March, he curled up on a mat, she said, begging her for porridge.

“I told him we don’t have any wheat to make that,” Fadul said. “He was suffering a lot and then he died around midnight.” His mother wept, she recalled, then asked the neighbors to help bury him.

She had done her best to keep them alive, she said, walking 10 hours each day to collect small bundles of firewood she could sell for about a dollar. Sometimes it was enough to buy wheat to boil in water; never enough for all the children, but the older ones could live on less.

The daily meal from the soup kitchen was a godsend, she said. Often the family would share a single bowl.

“You can’t ask your neighbors for anything because we are all in the same situation,” Fadul said. “We have nothing.”

In mid-May, the soup kitchen reopened, buoyed by funds from the Sudanese diaspora and the U.N. World Food Program. But many children are now so malnourished, doctors say, their stomachs cannot handle normal food. To survive, they need a special high-calorie supplement, and that, too, is hard to find.

Hundreds of thousands of doses of the lifesaving supplement — a peanut paste called Plumpy’Nut — have been paid for by the U.S. government and are sitting in a warehouse in Rhode Island, said Navyn Salem, the founder and CEO of Edesia Nutrition, which manufactures the paste.About 122,000 doses were due to go out in February to the U.N. Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in Sudan, Salem said, but their shipping contract was canceled amid the wave of USAID cuts. The supplies began moving again at the beginning of June, she said, but it will take more than a month to ship them all outNow, more stocks are piling up — 185,000 doses from the past fiscal year — but Salem said her factory has received no new orders.

“No business can survive this amount of uncertainty, and many children will not survive either,” she said. “The financial losses and the losses of human life are unimaginable and unacceptable.”

The small nutritional packets are desperately needed at the Almanar feeding center in the Mayo Mandela district of Khartoum, where mothers lined up last month carrying their starving children. Rahma Kaki Jubarra’s 9-month-old son, Farah, weighs just 12 pounds. Her other son, 3½-year-old Jabr, is down to just 21 pounds. The tape the medics wrap around their arms to measure their body fat slides far into the red, signaling an emergency.

Before the war, Jubarra said, she scraped by, selling falafel while her husband was a trader at the local market. When RSF fighters took over their neighborhood, they burned 200 homes, including hers, she said, and beat her husband, brother and eldest son so badly they fled. Jubarra and her two children now live in the ruins of their former home; a blanket draped over the charred walls is all that shields them from the merciless sun.

Jubarra scavenged fish bones from restaurants and boiled them to feed her children. Her elderly father, who was also beaten, was too ill to flee and stayed with her, which meant another mouth to feed. But the soup kitchens were closed, she said, and the price of wheat had quadrupled.

“Sometimes I boiled water on the fire and told them I am cooking and just to wait,” she said. She’d continue poking at the pot, she recounted, hoping her children would fall asleep before they realized no meal was coming.

She rattled off the names of children she knew who didn’t make it. Old people died. Her uncle died. Her father died. People went to Bashair, the nearest hospital, but Doctors Without Borders had pulled out after the facility was shot up by the RSF. As the fighting raged, no aid made it in.

Last month, UNICEF was able to deliver peanut paste to the Almanar feeding center. Liana Ashot Chuol, just 7 years old, showed up by herself on a recent morning. She was carrying her starving 3-year-old sister and pushing her 5-year-old brother. Her mother had disappeared, she whispered, her father was dead and her grandmother had gone looking for firewood to sell. None of the children had eaten for two days, Liana said.

Almanar director Amna Kornlues said that deaths have skyrocketed since the soup kitchens closed but that there is no way to know the true toll. Many children died at home, she said, and families stopped coming when the center ran out of aid to distribute.

She asked for the U.S. to continue its support: “All we need is a little, and we will share together,” Kornlues said.

If U.S. funding is not preserved, UNICEF could run out of Plumpy’Nut within a few months, it says, with dire consequences for those who depend on the nearly 2,000 feeding centers the agency supports across Sudan.

The U.S. cuts “force us to make extremely difficult decisions,” said Kristine Hambrouck, the acting U.N. representative in Sudan. Aid workers must choose between buying vaccines for babies or nutrition products for starving children, she said, and all could die without help.

Cholera spreads

Sickness here is just as dangerous as hunger.

Cholera, a waterborne disease that can kill within hours, swept across the capital in the past month after RSF drones attacked the filtration plant and electricity grid, knocking out the city’s water pumps. People are drinking from polluted rivers or contaminated wells, along streets where charred and bloated bodies have decomposed.

Soup kitchen manager Waleed Elshaikh Edris told The Post that dozens of people had died of cholera in a single day last month in his neighborhood of Al Fitehab, including his uncle and his cousin, who he said died only eight hours after she began to show symptoms.

“When artillery shelling was intense, we had solutions — we would go under buildings,” he said. “But this infection suddenly sneaks into your body without your knowledge.”

The World Health Organization said that its partner organizations are missing 60 percent of their medical supplies and that tracking and containing the outbreak have become all but impossible.

“Supplies for cholera response were largely funded by USAID,” said Loza Mesfin Tesfaye, a WHO spokeswoman, adding that “the cuts have reduced the number of disease surveillance teams [and] reduced our ability to distribute water-purifying supplies.”

At a mobile health clinic run by volunteers in the Salha district of Omdurman, elderly men were treated with bags of intravenous fluids hung from a mosque window. In what was once an upmarket restaurant in Omdurman, a young man curled up on a table, an intravenous tube sticking out from his hand.

Much of the cholera response has fallen to locals like Momen, a dreadlocked 33-year-old who slips out his front door on a bike every day at 5 a.m., carrying chlorine tablets — the most common way to disinfect water supplies — along with information leaflets and dreams of a different Sudan.

Momen gives the tablets to the tea ladies fanning battered pots on charcoal fires, to mothers with jerricans lining up at water wells, and drops them in the round blue communal tanks. As a pro-democracy activist during the 2019 uprising, he was arrested more than 40 times and shot in the arm, he said. Momen spoke to The Post on the condition he be identified by his first name for fear of being targeted by armed groups.

“When support was coming from USAID, we were able to respond and carry out emergency interventions much more quickly,” he said. Now, the volunteers have to design their own solutions and fundraise online, he said, which slows their work.

But he said nothing will stop them. “Our country needs us,” he said. “We are going to change Sudan.”