The Case for Humanitarian Airdrops in Darfur

Eric Reeves | April 23, 2025

As Sudan’s savagely destructive internal conflict enters its third year, the international community has shown no real sign of being able to halt the war or even influence the main actors. The relentless military and political ambitions of General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan (head of the Sudan Armed Forces) and Hamdan Dagalo (head of the Rapid Support Forces) remain in a death-lock.

These realities cannot simply be wished away; nor do expressions of “regret” over continuous war crimes and crimes against humanity—committed by both sides— register in any meaningful way. We must act to save lives.

Nowhere in Sudan at present is violence more threatening than in Darfur. And within Darfur, the very epicenter of human suffering and destruction is the El Fasher area of North Darfur. This became grimly evident 13 days ago when the RSF mounted a furious assault on Zamzam camp for internally displaced persons, some fifteen kilometers southwest of El Fasher city, capital of North Darfur. Zamzam was home to well over 500,000 people—mainly women and children—when it was attacked by the RSF beginning the evening of April 10. Using arson, machine-gun-mounted Toyotas, and other weapons, they completely destroyed the camp.

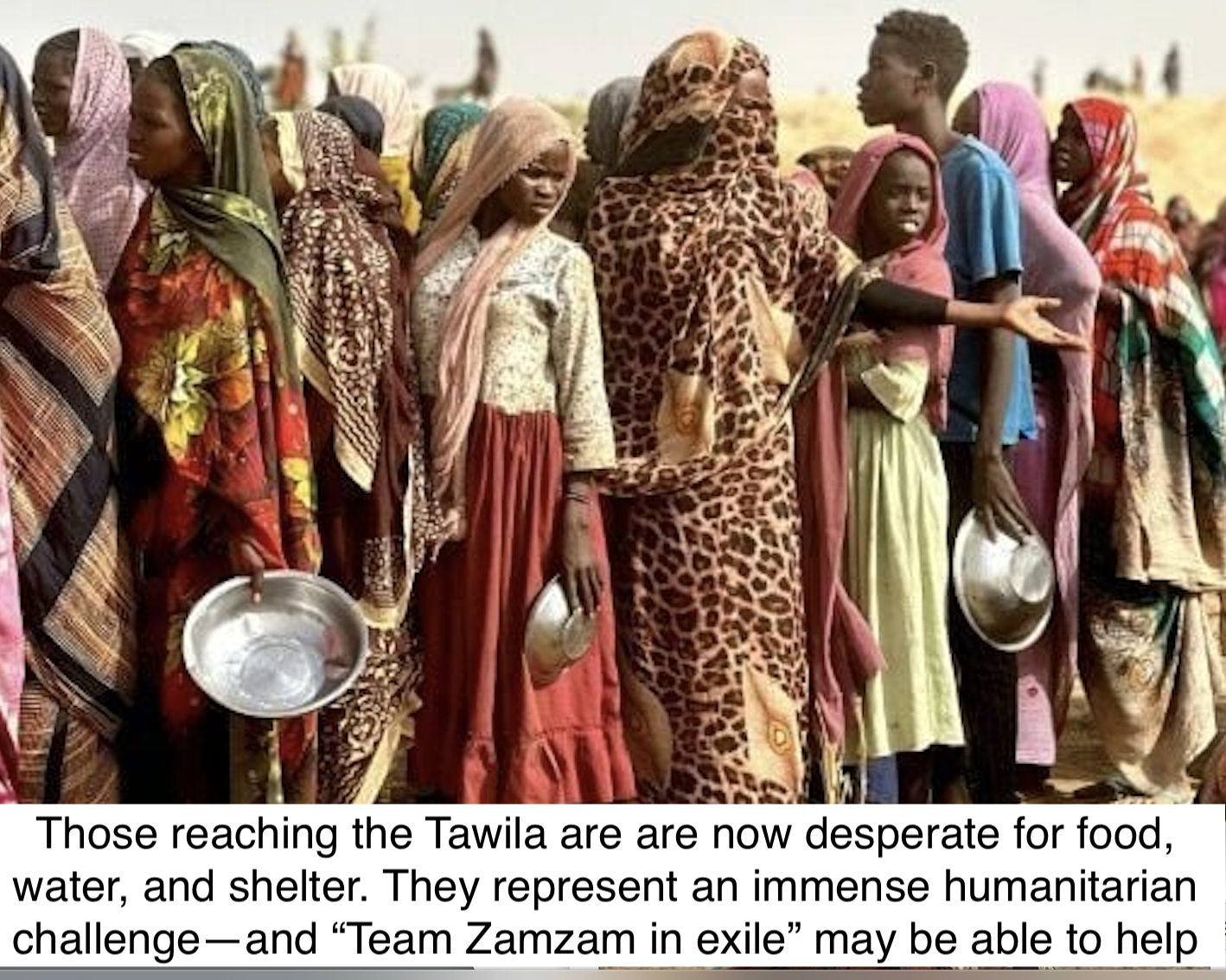

Following the assault, initial reports from the ground suggested that about 250,000 people fled to El Fasher, while another 150,000 fled to the west; they were trying to reach Tawila, 60 kilometers away in the foothills of the Jebel Marra massif, where there are some humanitarian operations. And some 100,000 people remain trapped in smoldering Zamzam, with RSF patrols sealing all exits. Most of these people have now died or managed to escape in whatever direction they could.

Each of these populations faces extreme dangers: continuing ethnically-targeted violence, as well as severe lack of food, water, and shelter. El Fasher city has been under siege by the RSF since April of last year and its citizens now find themselves virtually without food and water. Absorbing those fleeing Zamzam is overwhelming the city’s remaining, exceedingly limited resources. Many who fled initially to El Fasher are now attempting to reach the Tawila area.

People are already dying from the famine belatedly declared by the UN in August 2024, with Zamzam designated its epicenter. But the scale of mortality is poised to explode upward without urgent, substantial humanitarian relief. Yet the RSF is by denying access to aid and creating an insecurity that makes humanitarian convoys simply too dangerous. RSF hostility to humanitarians is all too well reflected in the deliberate, ruthless murder of all nine workers at a health clinic in Zamzam run by Relief International.

We cannot escape the moral challenge of the ongoing threat to so many hundreds of thousands of human lives. If convoys cannot reach El Fasher, then the UN or other international actors must begin a sustained program of humanitarian airdrops for El Fasher. These might originate in Port Sudan, where a great deal of food already has been stored; or they might originate in Chad’s eastern city of Ádre, also stockpiled with humanitarian aid.

To be sure, airdrops are a last resort—the least effective way to bring humanitarian relief to people in need, especially with no partnering humanitarian organization on the ground to distribute what is airdropped. But in the absence of any alternative, this effort must commence at once. And there are already precedents for airdrops in Darfur: twenty tons of medical supplies were airdropped into El Fasher last June; the UN’s WFP airdropped food into West Darfur (including Fur Buranga) last August; the humanitarian organization Samaritan’s Purse began airdropping food relief earlier this year.

With these precedents, we must ask what prevents the humanitarian community from beginning the large-scale, sustained humanitarian airdrops that are all that can save countless numbers of displaced persons. The American C-130, for example, can airdrop up to 18 tons of supplies in a single run. And whatever inefficiencies there are in such delivery, it is important to remember that the accuracy of airdrops has come a long way since Operation Lifeline that was so effective during the 1990s and beyond. Currently, there have been humanitarian airdrops in Gaza, with more than enough success to justify continuation.

In a 2021 assessment WFP pointed to the difficulties, but also the critical need in circumstances like those that prevail in Darfur. Useful overviews of the challenges and capacities of airdrops have been provided steadily since the first UN airdrop in 1973.* Accuracy, parachute design and manufacture, the ubiquity of GPS guidance, wind and weather assessment, and experience have all greatly increased the accuracy of humanitarian airdrops.

To be sure, it is possible that General al-Burhan’s de facto government will try to prevent such airdrops, despite approving earlier airdrops. If he does, he must be made to understand that there will be painful long-term consequences for him and the SAF if he refuses to yield. The U.S. and EU should demand of Egypt and Saudi Arabia that they pressure al-Burhan into agreeing.

President Déby of Chad may also object to use of Chadian territory for cargo planes flying into Darfur. But Déby is a very weak, unpopular leader who survives primarily because of financial aid from the United Arab EmiratesL we now have overwhelming evidence that the UAE has provided tremendous support for the RSF: small arms and high-tech weapons, ammunition, logistics, and cash. The UAE surreptitiously flies cargo planes into northeastern Chad and elsewhere, with cargos destined for the RSF. Déby and Chad are well aware of this and are therefore deeply complicit in the humanitarian crisis in Darfur; the must be held accountable, with punishing pressure on his regime is he refuses.

The issue, more broadly, is that the UAE has not been held to account for its central role in prolonging conflict in Sudan and exacerbating the world’s greatest humanitarian crisis. Emirati strongman Mohamed bin Zayed may try to pressure Déby into resisting humanitarian flights. But here especially the Emirates must be forcefully and openly challenged for their wholly destructive—and self-interested—role in sustaining its RSF proxy. Sufficient pressure from the UN, the U.S., and the EU can—and should—be exerted on the UAE and Déby to allow humanitarian cargo airdrops. Notably, Chad was the first beneficiary of the inaugural airdrop in 1973.

Not to make such an effort a priority at this urgent moment would compound the international community’s already shameful acquiescence before Sudan’s agony.

Not to make such an effort a priority at this urgent moment would compound the international community’s already shameful acquiescence before Sudan’s agony.

On the practicability of airdrops:

https://taskandpurpose.com/tech-tactics/how-us-humanitarian-aid-airdrops-work/

https://blogs.hanken.fi/humlog/2023/10/20/humanitarian-air-drops-an-option-of-last-resort/

For the past five years, Eric Reeves has worked to create, fund, and organize a humanitarian aid project in Zamzam IDP camp, originally focused on responding to girls and women traumatized by sexual violence but increasingly responding to the need for food aid.

He is a trustee of the Darfur Bar Association.