Understanding the RSF Amid Current Violence in Sudan

Eric Reeves, June 23/24, 2023

The conflict that began on April 15 with the attack by Hemedti’s forces against al-Burhan’s residence was all too predictable—and indeed predicted emphatically by many. The ensuing large-scale violence was the culmination of the impossible situation created by the August 2019 Constitutional Declaration, enshrining as legitimate both the SAF and RSF. Two ruthless generals, with two armies, in a desperately needy country was a formula for disaster, and some of us warned as much.

Legitimating the RSF and Hemedti was expedient in the extreme and simply ignored the realities of 2013 to 2019 in Darfur, where Hemedti was appointed by al-Bashir to command the newly created militia force (often called the “New Janjaweed” because of where primary recruitment occurred). With better weapons and funding, the RSF under Hemedti began a campaign that continued the genocide that began in 2003, but was allowed to continue, even with the presence of UNAMID. With ruthless, brutal tactics, the RSF conducted a widespread and intense campaign against non-Arab villages, as well as the remnants of the Darfur rebel groups. The destruction of civilian, noncombatant lives, property, and livelihoods was immense. This military destruction, and the growing power of the RSF, ultimately become Hemedti’s source of political power during the uprising of 2019.

By ignoring the fact that Hemedti was indeed another génocidaire, with all the vicious instincts this implied, the international community—as well as Sudanese civil society actors (mainly from Khartoum)—allowed Hemedti to convert the RSF into a lever of power in the formulation of the Constitutional Declaration, and ultimately into a role in the Sovereign Council, second in power only to General al-Burhan. A confrontation was built into this perverse arrangement, that relegated civilian governance to some finally indeterminate future.

The overthrow of al-Bashir ensured a fight for power, especially within the SAF; but civilians had demonstrated enough power, and organized that power, to wield a strong voice in negotiations prior to the August Constitutional Declaration. But an international community desperate for any kind of agreement ensured splits within the civilian opposition, and those splits have left legitimate civilian opposition mainly in the hands of the resistance committees, primarily in Khartoum.

But the conflict we now see, it must be emphasized, was the result of a “compromise” agreement that left the military (via the Sovereign Council) in charge of all real decision-making. And the prospect of real civilian governance led inevitably to the joint SAF/RSF coup of October 15, 2021. A year and a half later, after growing tensions between Hemedti and al-Burhan, the RSF commander brought his forces into Khartoum in large numbers. This made the current conflict inevitable.

Here again, however, we need to see clearly how the international community expediently legitimatized Hemedti in a desperate effort to negotiate a diplomatic settlement. This represented a serious misreading of Hemedti’s greater ambitions, and his commitment to survival by means of violence. The same violent instincts that guided Hemedti from 2013 to 2019 guide him now.

There was so little reporting on human rights abuses and atrocity crimes during this period that it is important to highlight how much of who and what Hemedti and the RSF could be clearly seen, certainly by Human Rights Watch in its authoritative report of 2015 (“‘Men with No Mercy’: Rapid Support Forces Attacks against Civilians in Darfur, Sudan,” September 2015”).

My own research during this period focused on two aspects of the genocidal nature of RSF in Darfur, and two resulting monographs contain data bases for all attacks reported (mainly by Radio Dabanga, with its extraordinary network of contacts and sources on the ground in Darfur):

“‘Changing the Demography’: Violent Expropriation and Destruction of Farmlands in Darfur, November 2014 – November 2015,” December 2015

“Continuing Mass Rape of Girls in Darfur: The most heinous crime generates no international outrage,” January 2016

If we want to understand what Hemedti and the RSF are, we could do no better than consider carefully the exhortation given to them by the Second Vice President of the al-Bashir regime, Hassabo Mohamed Abdalrahman. It is cited in a passage from the Human Rights Watch report (the Border Guards were effectively an auxiliary to the RSF):

Ahmed, a 35-year-old officer in the Border Guards, spent two weeks at a military base in Guba in December 2014 before being sent to fight rebels around Fanga. Two senior RSF officials, the commanding officer, Alnour Guba, and Col. Badre ab-Creash were present on the Guba base.

Ahmed said that a few days prior to leaving for East Jebel Marra, Sudanese Vice President Hassabo Mohammed Abdel Rahman directly addressed several hundred army and RSF soldiers:

“Hassabo told us to clear the area east of Jebel Marra. To kill any male. He said we want to clear the area of insects. … He said East Jebel Marra is the kingdom of the rebels. We don’t want anyone there to be alive.”

The Rapid Support Forces were all too successful in these efforts, particularly in East Jebel Marra. That Hemedti and the RSF have now been legitimized by the international community in multiple ways is fundamental to any understanding of how and the violence that began in Khartoum on April 15 continues—and is now clearly threatening Darfur and other regions of Sudan.

June 23, 2023

Eric Reeves, Fellow Rift Valley Institute

Northampton, Massachusetts

*************************

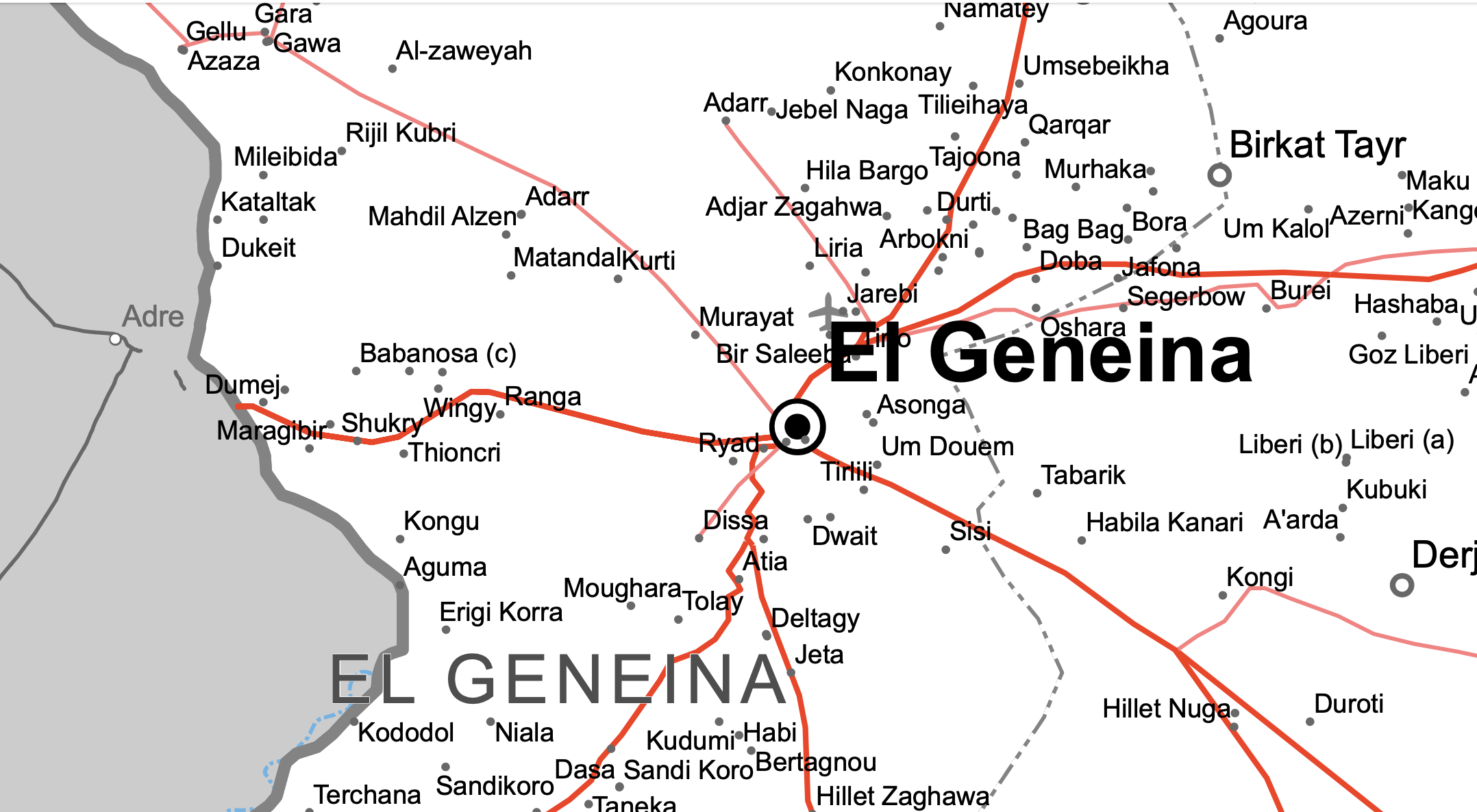

Addendum, June 24, 2023: What has happened in El Geneina

No city in Darfur has endured such brutal, sustained ethnically-targeted violence as El Geneina, capital of West Darfur. The violence that began in earnest in 2019 has culminated in the nearly complete destruction of the city and the displacement of tens of thousands of people, primarily those of the Masalit ethnic group. Most have fled to Chad, where they find woefully inadequate humanitarian relief. Many are dying from a lack of medicine, wounds suffered while still in El Geneina or fleeing toward Adre in eastern Chad.Food and water are in extremely short supply

Responsibility for what amounts to a genocidal campaign against the Masalit belongs to Hemedti’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and allied Arab militias, typically referred to by Darfuris as “Janjaweed.” This responsibility includes the killing of thousands of Masalit since 2019, including in the two Krinding camps for internally displaced persons.

Attacks on other of Darfur’s state capitals–notably El Fasher (North Darfur) and Nyala (South Darfur)–give credence to “chatter” on RSF social media that the larger strategy is to seize all of Darfur before withdrawing from Khartoum, and thus have a powerful bargaining “chip.” In any event, the future of Darfur—with no humanitarian corridor for food or medicine available to humanitarian organizations—is unspeakably grim, and the region as a whole faces violence and deprivation on full display in El Geneina:

Corpses litter the streets of El Geneina; many more are invisible within homes and shelters

Corpses litter the streets of El Geneina; many more are invisible within homes and shelters

The city has endured incredible levels of destruction at the hands of the RSF and their Arab militia allies

Most have lost everything and have no means to survive on their own in Chad

Many, such as this woman, have become ill or suffer from a complete lack of necessary medicine. A great many will die.