ANNEX : Project Update, March 28, 2023 : Responding to Sexual Violence in Darfur

Overview of violence in Khartoum and elsewhere in Sudan (Eric)

[I] By way of preface, let me emphasize that the stakes in the current conflict could not be higher, for Sudan and for the region: if the fighting does not end sometime in the next couple of weeks, the Sudanese state may start to come apart. Allies of both the RSF (e.g., the United Arab Emirates/UAE, Russia’s Wagner Group) and the SAF (e.g., Egypt)—as well as other regional actors—are waiting, with various motives, to see whether one side or the other prevails.

Of greatest immediate concern are the ominous signs of a catastrophic breakdown in humanitarian services, particularly in Khartoum, but inevitably spreading to other regions. Darfur, because of its remoteness, is especially likely to suffer from a breakdown in food and medical convoys by the UN’s World Food Program and other agencies. Following the murder of three UN WFP workers in the country (almost certainly by the RSF), all food operations—transport and delivery—have been halted.

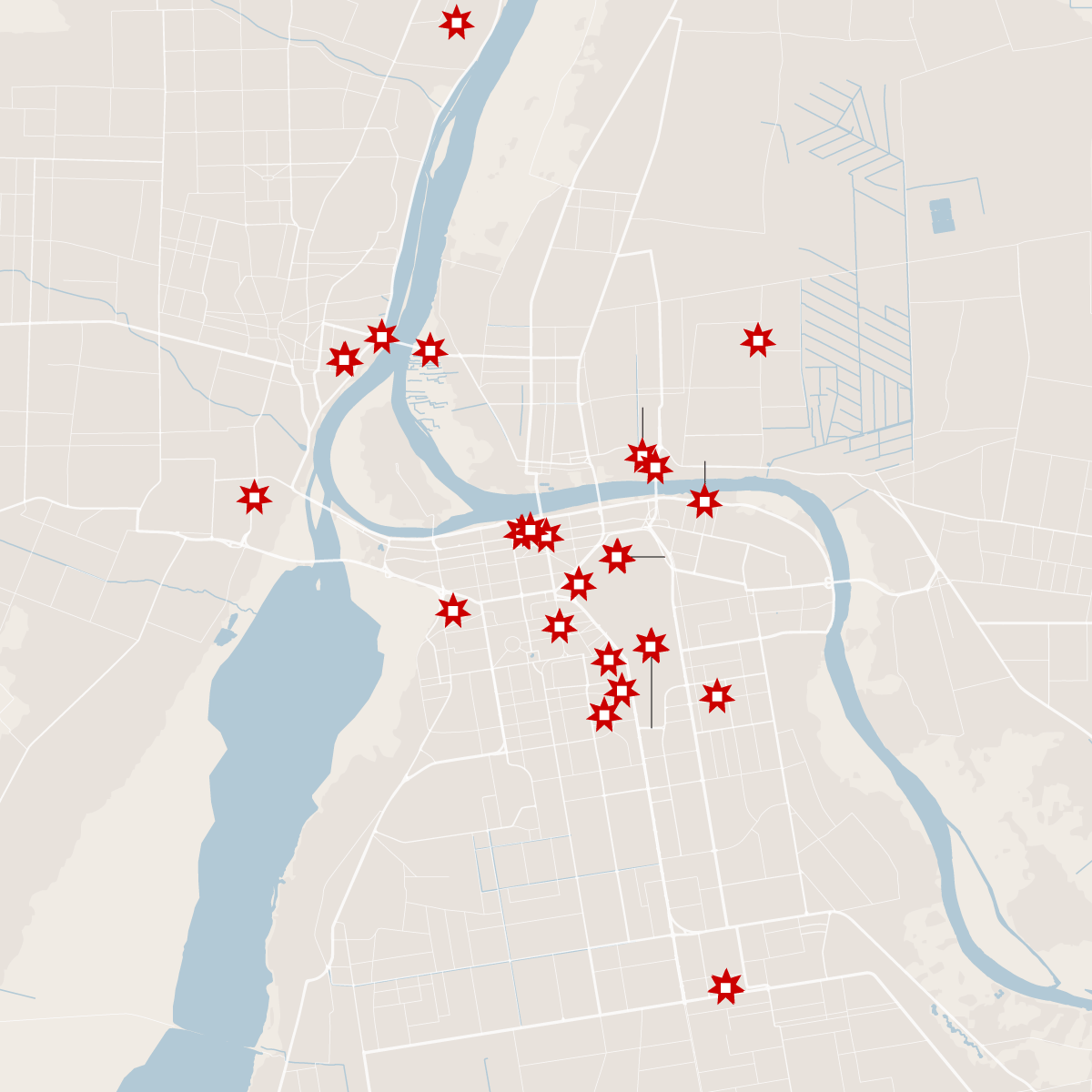

Khartoum is being destroyed by the fighting between the Sudan Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces

People are fleeing the city by the tens of thousands, as basis services and supplies are no longer available—including electricity, which is needed to pump water in many locations

An end to the violence seems nowhere in sight. The fourth internationally brokered cease-fire broke down on April 25, 2023 and there is little prospect for a negotiated end to the fighting. Al-Burhan feels that the SAF will prevail and wants to make sure that a cease-fire does not allow the RSF to re-supply and re-group.

An end to the violence seems nowhere in sight. The fourth internationally brokered cease-fire broke down on April 25, 2023 and there is little prospect for a negotiated end to the fighting. Al-Burhan feels that the SAF will prevail and wants to make sure that a cease-fire does not allow the RSF to re-supply and re-group.

Indiscriminate small arms, artillery and mortar fire, and air strikes (only the SAF has military aircraft) have dominated the fighting to date in Khartoum and the surrounding urban areas, with an almost unfathomably indiscriminate nature. Rape, looting, and murder have defined the behavior of an increasingly hunkered down RSF, which confronts diminishing chances for re–supply, re-grouping, and re-establishing command and control in many areas.

The RSF remain extremely dangerous, however, and their actions pose a grave threat throughout Khartoum and Sudan. To liberate captured comrades, the RSF has attacked and released thousands of prisoners from a number of prisons, including the infamous Kober prison, where former president and génocidaire Omar al-Bashir was being held (his whereabouts are presently unknown). Many of the men released during these brazen attacks are extremely dangerous and they will be completely unconstrained in their actions.

More ominous still is the RSF seizure of an important laboratory in the city. The BBC reports:

The World Health Organization told the BBC on Tuesday that workers can no longer access the lab. And it warned that power cuts were making it impossible to properly manage material at the lab. Officials said that a broad range of biological and chemical materials are stored in the lab. The facility holds measles and cholera pathogens, as well as other hazardous materials. A lack of power is also putting depleting stocks of blood bags stored at the lab at risk of spoiling.

(BBC, April 25, 2023, “The World Health Organization (WHO) says there’s a “high risk of biological hazard” at a laboratory caught up in the ongoing conflict in Sudan.”)

Agence France-Presse reports on the same ominous events:

Fighters have occupied a national public laboratory in Sudan holding samples of diseases including polio and measles, creating an “extremely, extremely dangerous” situation, the World Health Organization warned Tuesday. Fighters “kicked out all the technicians from the lab… which is completely under the control of one of the fighting parties as a military base,” said Nima Saeed Abid, the WHO’s representative in Sudan. [Other evidence strongly suggests that this “fighting party” is the RSF—ER]

“There is a huge biological risk associated with the occupation of the central public health lab,” said Abid. He pointed out that the lab held so-called isolates, or samples, of a range of deadly diseases, including measles, polio, and cholera.

The UN health agency also said there had been 14 attacks on healthcare facilities or personnel during the fighting, leaving eight healthcare workers dead and two injured. And it warned that “depleting stocks of blood bags risk spoiling due to lack of power.”

The RSF is a supremely callous force on the ground, widely despised by ordinary Sudanese (they are typically not seen as Sudanese, but rather Chadian or from the western hinterlands). Many have found shocking the following Tweet from someone who remains in Khartoum and has Internet access (for now—I omit his last name):

Shaheen (educator and civil servant)

- Went to 60 street to get bus info, found a friend at tea lady and sat to talk. A group of RSF soldiers sitting nearby wearing civilian clothes over uniforms in the chairs started calling back 2 homeless kids who walked by, it didn’t seem threatening —

- We continued into our conversation and suddenly saw with the side of our eyes one of the soldiers drag the first kid into the street, he then shot both his legs with his AK. We froze and another kid moved and was shot, that’s when we ran a bit further —

- A third kid was executed in their spot. I walked back hurriedly after they got into their stolen pick-up truck and left. There was nothing I could do but wrap the wounded legs with my shirt and others who took theirs off.

In its devastating 2015 report on the actions of the Rapid Support Forces in Darfur, Human Rights Watch chose a particularly apt title: “Men With No Mercy.”

Of greatest concern is the rapidly escalating humanitarian crisis: most pressing now in Khartoum, but destined to spread throughout Sudan if the chaotic violence does not end soon. Convoys of food and medicine are presently impossible for humanitarian organizations to undertake, and normal commercial trade and transportation has all but come to a halt. Zamzam camp has to date been relatively unaffected by the violence, although some of the camp’s residents have experienced a resurgence of trauma. Zamzam is in some sense a world unto itself. But it is in a geographically perilous location and food supplies are already critically low; without foodstuffs coming from the east in the near future, already extremely high malnutrition rates will become immensely destructive of human life and well-being.

Not only food but water and electricity are also in increasingly short supply in Khartoum and elsewhere; and fuel, whether for cooking or transport, has become exceedingly scarce and for many prohibitively expensive. Pumping water is impossible in many areas and the absence of electricity means that phones cannot be charged, and Internet access has been largely shut down. Journalists remaining in Khartoum, and able to report out, are doing an extraordinary and extraordinarily courageous job; but journalists too are in most cases attempting to leave Khartoum.

One dispatch relates the plight of a Sudanese doctor:

Agonising choice of NHS doctor fleeing Sudan has left her riddled with worry and guilt; Dr Iman Abugarja had to face an unthinkable decision: to stay with her elderly, sick parents or get her children to safety. (Sky News (UK), April 25, 2023)

Many face similarly agonizing choices.

[II] How did this almost unimaginably dangerous state of affairs come to pass? I have written extensively about the question in the past, on my website and Twitter, but here in particular I will defer to several superb, very recent analyses, in particular that of Azza Ahmed Abdel Aziz in Middle East Eye (April 25, 2023). In “Sudan is at risk of unravelling from decades of injustice,” she argues at length, and with a comprehensive understanding of Sudan’s recent political history, that “the civil war raging in Khartoum is a culmination of the violence to which the Sudanese state has subjected its citizens over many years.” The wars against the peripheries—whether South Sudan, the people of the Nuba, or Darfur—have defined the idea of “security” held by all the leaders who have virtually all come from the riverine elite.

A fine account of recent international diplomatic failures is offered by The Guardian (April 25, 2023): “‘The worst of worst case scenarios’: western diplomats blindsided over Sudan crisis.”

As the piece notes, Khartoum residents and regional experts have long said that the international community and humanitarian organizations should have been better prepared for violence. In fact, all the evidence of what was building in Khartoum was clear to any who would look. This clearly did not include the Special Representative of the UN Secretary General, the feckless and incompetent Volker Perthes:

“This is the worst of worst case scenarios,” Volker Perthes said. “We tried even with last ditch diplomacy … last week and we have failed.”

Was there no warning, one staff member asked? “No, we did not have any early warning,” Perthes said, according to minutes of the meeting viewed by The Guardian.

But others disagree, saying that governments and international organisations should have been much better prepared for the crisis. They say it was always clear that army units loyal to Sudan’s military ruler, Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, would end up fighting the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti, and that warning lights were flashing red long before 15 April, when the shooting started.

Residents of Khartoum say they have been warning about such a clash for months. Both factions had been mobilising for a struggle, stockpiling ammunition, accelerating recruitment, bringing in extra fuel and medical supplies, even blood. Two nights before the outbreak of violence, there was none of the usual buzz of an evening during Ramadan in Khartoum’s cafes and restaurants.

How could Perthes not have seen what was so clear to so many others, including this writer? The entire article in The Guardian is extremely well-informed—and a devastating indictment of not just UN diplomacy.

A former U.S. adviser to the U.S. Special Envoy for the Sudans, Jacqueline Burns—who began her service in 2011—wrote a painfully honest op/ed in The New York Times this week, which concluded—all too accurately:

The international community should not stop trying to end violent conflicts, but future efforts must consider who matters for peace and who does not. The insidious nature of contemporary international conflict resolution is that, in its single-minded drive to get armed groups to put down their guns, those fighting for the real and lasting reforms necessary for peace too often get cast aside.

But the expediency she defines here was at the very heart of diplomacy of the man she served, Princeton Lyman:

“We [the Obama administration] do not want to see the ouster of the [Khartoum] regime, nor regime change. We want to see the regime carrying out reform via constitutional democratic measures.” (Princeton Lyman, former U.S. Special Envoy for the Sudans during the Obama administration, interview with Asharq al-Awsat, December 3, 2011 | http://english.aawsat.com/2011/12/article55244147/asharq-al-awsat-talks-to-us-special-envoy-to-sudan-princeton-lyman )

I would argue that this view of the genocidal regime of Omar al-Bashir did more to smother the nascent move toward democratic reform in Sudan than the actions or policies of any other international actor, including during the first brief domestic effort to kindle an “Arab Spring” in Sudan 2013.

Violence in Sudan has already brought to the fore the actions and ambitions of regional and international actors. Much is obscure or unclear, but reports from a wide range of sources strongly suggests the involvement of:

- The United Arab Emirates (UAE)

- Egypt (which fears both Ethiopia’s “Renaissance Dam” project and vehemently opposes civilian governance

- The Russian Wagner Group, headed by the notorious Yevgeny Prigozhin (“Putin’s chef”)

- Chad (ruled by men from non-Arab Zaghawa ethnic group, and fearful of the Reizegat Arab group from which Hemeti comes

- Libya and in particular the military forces of commander Khalifah Hafter

- Saudi Arabia (which strongly opposes civilian governance in Sudan

- Ethiopia (which has major concerns about Egypt’s vehement objections to the country’s “Renaissance Dam”

- Central African Republic (where the Wagner Group is especially strong)

- South Sudan (which shares oil revenues with Sudan)

- Countries with significant national populations inside Sudan

Indirectly, the entire international community is threatened by the disintegration of Sudan, something that in the minds of several of these actors creates opportunities for expanded power.

Below I offer a compendium of news sources, with excerpts. The situation on the ground may shift dramatically, but presently I judge the following to be the best reporting.

(all emphases in bold are mine)

The Wall Street Journal, April 23, 2023

The Russian paramilitary group Wagner has offered heavy weapons to the Rapid Support Forces, the militia run by Lt. Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, the Wall Street Journal has reported. Gen. Dagalo’s rival, Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the commander of Sudan’s military and the country’s de facto head of state, meanwhile, has received support from neighboring Egypt, the Journal has also reported.

Egypt has a more immediate interest than most in how the drama unfolds. Sudan’s northern neighbor wants Khartoum’s help to oppose a massive dam and reservoir farther south on the Nile by Ethiopia. Cairo fears the project could choke off the freshwater for millions of Egyptians and cripple its agriculture.

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah Al Sisi has thrown his weight behind Gen. Burhan, who, like the Egyptian leader, seized power through a coup. He has already sent jet fighters and pilots to support Sudan’s air force, bolstering Gen. Burhan’s control over the country’s skies and his ability to strike his rivals’ positions from the air.

In addition to Wagner’s offer of weapons, including shoulder-mounted antiaircraft missiles, Gen. Dagalo has received at least one shipment of ammunition from a Libyan militia leader backed by Russia and the United Arab Emirates, the Journal also reported.

[The UAE provides the largest market for Sudanese gold, and it is gold wealth that has given Hemeti so much of his power—ER]

There were no indications that Moscow or the U.A.E. had a hand in ordering the reinforcements sent by Khalifa Haftar, the commander of a faction that controls eastern Libya. But both nations have in recent years forged close ties to Gen. Dagalo, a former camel herder better known by his nickname, Hemedti.

The U.A.E., like Saudi Arabia, has spent billions of dollars buying up farmlands irrigated by Sudan’s section of the Nile to secure food for its own desert-dwelling population. It hired the RSF to fight in Yemen, supplying the militia with extra resources to take on Gen. Burhan and the military.

In December, a U.A.E.-based consortium signed a $6 billion deal to build a new port facility on Sudan’s Red Sea coast.

Sudan’s ports are the only point of export for around 135,000 barrels of oil a day produced inside the country and neighboring South Sudan. They are also the main gateway for goods to and from landlocked, mineral-rich Central African nations such as Chad and the Central African Republic.

For the U.S., the bigger concern is Russia’s potential impact on the conflict and Moscow’s ability to use Sudan to exert power in the region and help fund its campaign in Ukraine.

Gen. Dagalo has close ties with Russia and the Kremlin is awaiting final signoff from Sudan’s leadership on a 25-year lease for a naval base in Port Sudan, around 1,000 miles north of the biggest U.S. military base in Africa. The Russian base would hand the Kremlin’s warships access to the Suez Canal and the Indian Ocean in the middle of Moscow’s greatest confrontation with the U.S. and Europe in a generation.

U.S. military officials say they believe that Russia sees the base as a way to facilitate the extraction of gold, rare-earth minerals and other resources from Sudan and Central Africa.

Companies controlled by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a key ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin and the owner of Wagner, have been mining gold in Sudan for several years, according to the U.S. government, the European Union and Sudanese officials. The companies rely on RSF fighters to protect the sites in east and west Sudan, Sudanese officials and diplomats in the region say.

Wagner has also provided weapons and training to the militia, these people say, while Gen. Dagalo’s family controls a company that processes tailings from Russian-run mines. In response to questions from the Journal, Mr. Prigozhin said the paramilitary group “is in no way involved in the Sudanese conflict.”

Russian investments have helped increase Sudan’s annual gold production to around 100 tons in 2021 from as little as 30 tons five years ago, according to Finance Ministry data. Officials at the Sudanese central bank and the state mining company say they estimate that around 70% of the country’s gold is exported to Russia, often via middlemen in the U.A.E. and other countries.

[In short, Sudan’s gold is helping Putin to evade sanctions and fund the war in Ukraine—ER]

The Guardian, April 20, 2023

Hemedti owns, along with other family members, a gold mining company that operates in lands he seized in Darfur 2017. In 2018, Bashir gave Hemedti permission to mine and sell gold, and operations extended to other gold rich areas in outside Darfur in the south of the country. The gold was exported, according to a 2019 Reuters investigation, circumventing capital controls, and even sold to the Sudanese central bank for a preferential rate. The yield was allegedly used to enrich Hemedti and his family, and fund the expansion of the RSF. (A spokesperson for Hemedti denied these allegations to Reuters.)

Sudan is Africa’s third-largest producer of gold, and one of the poorest countries in the world. Yet the Dagalo fortune is not one that Hemedti, or the rest of his family, is discreet about. Hemedti sees no conflict between his political role and his business interests. “I’m not the first man to have goldmines,” he told the BBC in 2019. In a video posted last year, Hemedti’s cousin boasted that the Dagalos have become “one of Africa’s richest families”.

Beyond a tool for domestic power and making money, the RSF gives Hemedti geopolitical power. By sending his forces to Yemen to support Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s war against Houthi rebels – by 2017, according to reports, there were as many as 40,000 RSF troops in Yemen – Hemedti secured powerful allies. After the revolution that ousted Bashir, Saudi Arabia and the UAE sent $3bn to stabilise the prospects of the military-RSF junta. That alliance extended into Libya, where in 2019, 1,000 RSF troops were sent to support UAE-allied forces of Khalifa Haftar in his offensive on Tripoli.

The Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar helped to prepare the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a militia now fighting for control of Sudan, for battle in the months before the devastating violence that broke out on 15 April, the Observer has been told by former officials, militia commanders and sources in Sudan and the UK.

The involvement of Haftar, who runs much of the eastern part of Libya, will raise fears of a long-drawn-out conflict in Sudan fuelled by outside interests. Analysts have described a “nightmare scenario” of multiple regional actors and powers fighting a proxy war in the country of more than 45 million people….

The involvement of Haftar, who runs much of the eastern part of Libya, will raise fears of a long-drawn-out conflict in Sudan fuelled by outside interests. Analysts have described a “nightmare scenario” of multiple regional actors and powers fighting a proxy war in the country of more than 45 million people….

Local NGOs are warning staff to brace for a rise in violence now that the Muslim holy month of Ramadan is over. The sources told the Observer that Haftar had passed on crucial intelligence to Hemedti, detained his enemies, increased deliveries of fuel and possibly trained a detachment of hundreds of fighters from the RSF in urban warfare between February and mid-April.

Haftar’s connection with Hemedti goes back to well before the fall of Omar al-Bashir, Sudan’s veteran authoritarian ruler, after months of popular protests in 2019. However, the relationship has grown warmer in recent years, with Hemedti sending mercenaries to Libya to fight alongside Haftar’s military force, the self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA), the sources said.

Hemedti and Haftar have also collaborated on a range of highly profitable smuggling operations, with middle-ranking commanders in both their militias forging close links as they manage the transit of valuable illicit cargos between the two countries, experts told the Observer.

Sudan and Libya sit astride major routes for human trafficking, narcotics and much else. In recent weeks, as conflict between the RSF and Burhan’s forces loomed, Haftar made efforts to support Hemedti, the sources said.

These have been carefully calibrated, however, as neither Haftar nor his international sponsors, the United Arab Emirates and Russia, want to commit entirely to one side in a conflict whose likely outcome remains unclear. Haftar must also be careful not to alienate supporters in Egypt who are backing Burhan. One militia commander within the LNA said his force was “ready to support [Hemedti] … but we are still monitoring the unfolding situation in Sudan.”

Only days before the conflict erupted, Haftar ordered the arrest of a deputy of Musa Hilal, a Sudanese militia commander who is a bitter enemy of Hemedti. Hilal’s forces were responsible for inflicting heavy losses on Russian mercenaries from the Wagner group – another ally of Haftar – in the neighbouring Central African Republic in an ambush near the Sudanese border earlier this year.

In a further display of support, one of Haftar’s sons flew into Khartoum to donate $2m to Al-Merrikh Club, one of two big football teams in Sudan which is struggling financially. The club is associated with Hemedti, who has helped to repair its stadium. After announcing the gift, Sadeeq Haftar was hosted by Hemedti.

During the visit, Hemedti received a warning from Haftar that his rivals in Sudan were preparing to move against him, intelligence sources close to the LNA told the Observer. A day after Haftar’s son had left Sudan, Hemedti moved forces to take control of the international airport at Merowe, a strategically sited town 300km north of Khartoum, and began positioning fighters to seize key locations in the capital, the sources said. Last week, the Wall Street Journal reported that Haftar had sent at least one shipment of arms to Hemedti, a claim denied by the LNA, while CNN described flights from LNA-run airbases organised by the Wagner group, which has a presence in both Libya and Sudan.

Russia has built close ties with both Haftar and Hemedti, but Yevgeny Prigozhin, the founder of the Wagner group, denied the report.

There are, however, reports from witnesses on the ground of planes landing at Al-Jawf airport in Kufra, in southern Libya, carrying weapons that then were sent on convoys of trucks towards Sudan. Haftar is a polarising figure, whose enemies accuse him of war crimes during Libya’s 2014-20 civil war. In 2019, a UN report said that a thousand Sudanese troops from the RSF had been deployed to Libya by Hemedti to help the LNA in its battle with the internationally recognised government in Tripoli.

Former and current Libyan officials told the Observer that in recent months Haftar had trained hundreds of RSF fighters, who lack experience of urban warfare, in techniques and tactics they would need in a potential battle for Khartoum and other cities.

Jalel Harchaoui, an expert on Libya and associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, said support from Haftar and his sponsors would be carefully judged. “They want [Hemedti] to survive, at least … Fuel makes more sense than weapons or ammunition and is the surest thing [Hemedti] could get from Libyan friends,” Harchaoui said.

The fuel shipments are being delivered by truck from the Mediterranean port of Benghazi, the sources said, although others suggested a likely additional origin might be the more southerly Sarir refinery, which has recently been requisitioned by the LNA. Hemedti’s forces are short of fuel because supplies to their main bases in Darfur have been cut by Burhan’s supporters in Khartoum, who still control much of the oil and petrol infrastructure in Sudan.

CNN, April 21, 2023

Exclusive: Evidence emerges of Russia’s Wagner arming militia leader battling Sudan’s army

By Nima Elbagir, Gianluca Mezzofiore, Tamara Qiblawi and Barbara Arvanitidis, CNN

April 21, 2023

The Russian mercenary group Wagner has been supplying Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces with missiles to aid their fight against the country’s army, Sudanese and regional diplomatic sources have told CNN.

The sources said the surface-to-air missiles have significantly buttressed RSF paramilitary fighters and their leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo as he battles for power with Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, Sudan’s military ruler and the head of its armed forces. In bordering Libya, where a Wagner-backed rogue general, Khalifa Haftar, controls swathes of land, satellite imagery supports these claims, showing an unusual uptick in activity on Wagner bases.

The powerful Russian mercenary group has played a public and pivotal role in Moscow’s foreign military campaigns, namely in Ukraine, and has repeatedly been accused of committing atrocities. In Africa, it has helped to prop up Moscow’s growing influence and seizing of resources.

Satellite images show increased activity

Satellite images analyzed by CNN and open-source group “All Eyes on Wagner” show one Russian transport plane shuttling between two key Libyan airbases belonging to Haftar and used by the sanctioned Russian fighting group.

Haftar has backed the RSF, sources say, although he denies taking sides. And increased Wagner activity at Haftar’s bases, combined with claims by Sudanese and regional diplomatic sources, suggests that both Russia and the Libyan general may have been preparing to support the RSF even before the eruption of violence.

The uptick in movement by the Ilyushin-76 transport aircraft started two days before the conflict in Sudan began on Saturday, and continued until at least Wednesday, according to satellite images and Netherlands-based open-source specialist Gerjon.

That plane, one of a class of aircraft known by the NATO designation Candid, flew from Haftar’s Khadim airbase in Libya to the Syrian coastal city of Latakia – where Russia has a major airbase – on Thursday, April 13. The next day, it flew from Latakia back to Khadim. The day after that, it flew again to another Haftar airbase in Libya’s Jufra. It parked in a secluded area, something flight tracker Gerjon considered highly unusual. This was the day the conflict erupted.

The transport plane returned to Latakia on Tuesday before flying back to the Libyan militia airbase of Khadim and then to Jufra, according to Gerjon’s research. That day, Russia airdropped surface-to-air missiles to Dagalo’s militia positions in northwest Sudan, according to regional and Sudanese sources. For years, Dagalo has been a key beneficiary from Russian involvement in Sudan, as the primary recipient of Moscow’s weapons and training.

A July 2022 CNN investigation exposed deepening ties between Moscow and Sudan’s military leadership, who granted Russia access to the east African country’s gold riches in exchange for military and political support. The relationship began in earnest after Moscow’s 2014 invasion of Crimea, when Russia began to eye African gold riches as an avenue to circumvent a slew of Western sanctions.

The 2022 invasion of Ukraine and the wave of sanctions that followed accelerated Russia’s gold plunder in Sudan and further propped up military rule, increasing Wagner activity in the country. On the day before Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Dagalo headed a Sudanese delegation in Moscow to “advance relations” between the two countries.

Burhan and the Sudanese army also previously received backing from Russia. Burhan and Dagalo were allies before the start of the fighting. Together they led coups in 2019 and 2021. Both leaders were also previously backed by the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Both Middle Eastern powerhouses have called for calm in Sudan, amid fears of broader regional repercussions.

Yet foreign actors are already beginning to intervene in the conflict. Egypt has a long-standing relationship with Burhan and has privately backed him in the power struggle, according to Sudanese and regional diplomatic sources. A group of Egyptian soldiers were captured by the RSF at a military airport in northern Sudan on the first day of the violence, and released days later.

In a statement to CNN, the RSF denied receiving aid from Russia and Libya. It reiterated its denial on Friday and alleged that its rival, al-Burhan’s Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), had aligned itself “with these foreign forces, not RSF.”

The New York Times

As War Rages in Sudan, Countries Angle for Advantage

Even before its two leading generals went to war last week, “everyone wanted a chunk of Sudan,” an expert said of the strategically located country rich in natural resources.

April 22, 2023 NAIROBI, Kenya

As war consumes Sudan, nations from around the world have mobilized swiftly. Egypt scrambled to bring home 27 of its soldiers, who had been seized by one of Sudan’s warring parties. A Libyan warlord offered weapons to his favored side, American officials said.

Diplomats from Africa, the Middle East and the West have appealed for a halt to the fighting that has reduced parts of the capital, Khartoum, to a smoking battlefield. Even the leader of Russia’s most notorious private military company, Wagner, has gotten involved. Publicly, he has offered to help mediate between the rival generals fighting for power, but American officials say he has offered weapons, too.

“The U.N. and many others want the blood of the Sudanese,” Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Wagner founder, said in a statement. Without a hint of irony, Mr. Prigozhin, who is waging a brutal military campaign on behalf of Russia in Ukraine, added: “I want peace.”

The rush of international activity may seem sudden, but it reflects a dynamic that loomed over the country well before its two leading generals turned on each other last week: Sudan has been up for grabs for years.

The revolution of 2019 — in which tens of thousands of protesters ended the three-decade dictatorship of President Omar Hasan al-Bashir — was supposed to usher in a bright and democratic future. But it also spelled new opportunities for outside powers to pursue their own interests in Africa’s third largest country — a nation strategically perched on the Nile and the Red Sea, with vast mineral wealth and agricultural potential, and which only recently emerged from decades of sanctions and isolation.

Russia sought naval access for its warships in Sudan’s Red Sea ports. Wagner gave armored vehicles and training in return for lucrative gold mining concessions. The United Arab Emirates paid one of the warring Sudanese generals, Lt. Gen. Mohamed Hamdan, to help it fight in Yemen, officials say. Egypt backed the other general, Gen. Abdul Fattah al-Burhan, sending soldiers and warplanes in a highly contested show of support. Israel, long shunned in the Arab world, saw a chance to gain something it coveted from Sudan: formal recognition.

And Western countries pushed what may have been the most difficult idea of all — the transition to democracy — while also hoping to counter the expanding influence of China and Russia in Africa.

Violence in Sudan

Fighting between two military factions has thrown Sudan into chaos, with plans for a transition to a civilian-led democracy now in shambles.

- Understand the Fighting: Looking at the history of coups — both the successes and the failures — can help put the chaotic eventsunfolding in Sudan into clearer perspective.

- Fleeing the Country: Theevacuation of American diplomats from Sudan’s besieged capital has turned into a full-fledged exodus of foreigners. The fighting has also driven thousands of Sudanese into neighboring countries.

- Tilting Sudan Toward War: For years, foreign powers sought an advantage in mineral-rich Sudan by offering weapons. Their angling made the conflict more likely.

“Everyone wanted a chunk of Sudan and it couldn’t take all the meddling,” said Magdi el-Gizouli, a Sudanese analyst at the Rift Valley Institute, a research group. “Too many competing interests and too many claims,” he added, “then the fragile balance imploded, as you can see now.” As some foreign powers picked sides, and even delivered weapons, they weakened Sudan’s pro-democracy forces and helped tilt the country toward war by bolstering the military rivals now fighting it out on the Khartoum streets.

In 2018, the Emiratis paid General Hamdan to send thousands of troops to fight in Yemen — a conflict which, Sudanese officials said, enriched the general. The Emirati foreign ministry declined to comment. General Hamdan also grew rich from gold mined in Sudan and shipped to Dubai. He visited Russian officials in Moscow at the start of the Ukraine invasion and partnered with Wagner in return for a license to mine gold in Sudan.

General Hamdan’s wealth includes livestock, real estate and private security firms, several Western officials said. That money, much of it held in Dubai, helped him to build up his paramilitary forces, which are now better equipped than the regular Sudanese military — yet another point of friction between the two sides.

The leader of the U.A.E., Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed al Nahyan, is one of just three heads of state that have publicly met General Hamdan, most recently in February, conferring the statesman aura he evidently craved. (The others are the leaders of Eritrea and Chad.)

But General Hamdan’s closest ally in the Emirates, according to diplomats in Sudan, is the country’s vice-president, Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed al Nahyan, owner of Britain’s Manchester City soccer club, who has longstanding contacts with armed groups in Darfur, General Hamdan’s home region.

[E]ven as fighting has raged, some weapon supplies have continued to flow. American officials say that General Hamdan has been offered weapons from Khalifa Hifter, a Libyan warlord who has also been armed and funded by the U.A.E. Officials say it is unclear if those weapons are from Mr. Hifter’s own stocks, or from the U.A.E. Egypt, a much bigger, if poorer, Arab nation, is on the other side of Sudan’s military divide.

As tensions grew inside Sudan in the past year, Egypt’s president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, openly sided with the army chief, General al-Burhan. The pro-democracy revolution that toppled Sudan’s president is inimical to Mr. el-Sisi, a military general who has ruled with an iron fist since coming to power in a coup in 2013.

He is also deeply suspicious of General Hamdan, a onetime militia leader, preferring to see Sudan ruled by a formally trained officer like himself. There is also a personal connection: Mr. el-Sisi and General al-Burhan attended the same military college.

Earlier this year, Egypt launched a political initiative in Cairo to bring together the Sudanese factions. But foreign diplomats in Khartoum, who were trying to work out a compromise between General Hamdan and General al-Burhan, saw the Egyptians as spoilers, acting in favor of the Sudanese military — and against General Hamdan.

“Egypt has made it clear that it will not tolerate a militia leader on its southern border,” said Cameron Hudson, a former C.I.A. analyst, now an Africa specialist at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

Tensions over Egypt’s role in Sudan helped propel the generals to war. On April 12, three days before the fighting erupted, General Hamdan’s paramilitaries surrounded a military base in Merowe, 200 miles north of Khartoum, where Egyptian soldiers and about a dozen Egyptian warplanes were stationed.

The move set off a public riposte from the Sudanese military, which insisted the Egyptians were there on a training exercise. General Hamdan evidently feared the Egyptians had come to provide air support to his enemy, Sudan’s military, in the event of a fight.

When the conflict erupted, General Hamdan’s forces captured at least 27 Egyptians from the Meroe base — prompting an intensive effort by Western officials to defuse the crisis and avoid the prospect of a widening, regional conflict. That drama appeared to end on Thursday, when General Hamdan’s forces handed over the Egyptian detainees. But the risk of Egypt being sucked into Sudan’s conflict remains, Western officials said.

As the battle for the capital has escalated in recent days, General Hamdan’s paramilitaries have been pummeled by warplanes firing rockets and dropping bombs on Khartoum, a densely populated city with millions of people. But in recent days the Rapid Support Forces have received an offer of powerful weapons, including surface-to-air missiles, from Mr. Prigozhin, American officials said.

Israel, too, has a stake. With American backing, it signed a deal to normalize relations with Sudan in 2020. Last year, a delegation from Mossad, Israel’s foreign intelligence agency, visited Sudan for meetings with security leaders including General Hamdan, who offered counterterrorism and intelligence cooperation, according to Western and Sudanese officials familiar with the talks.

Radio Dabanga

Chad fears rising tribal tensions if RSF wins, as up to 20,000 Sudanese refugees crossed its border

(April 24, 2023 | KHARTOUM / N’DJAMENA)

The clashes in Sudan are worrying its neighbour, Chad. The two countries share a complicated past and leaders fear rising ethnic tensions as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) commander has important ties to Chadian Arab tribesmen. As many as 20,000 people from Darfur have fled to neighbouring Chad in the past week, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) said.

United Nations refugee agency “is greatly alarmed by the escalating violence as the first refugees fleeing the fighting have found safety in Chad,” the deputy spokesman for the UN Secretary-General reported. The majority of the estimated 10,000 to 20,000 people who have fled the conflict in the Darfur region to seek refuge in Chad are women and children, the agency reported. People from the Tendelti area in West Darfur were amongst those who sought refuge in Chad out of fear of the ongoing battles between the army and the Rapid Support Forces.

Sudanese soldiers in Chad

Not long after the outbreak of the violence on Saturday April 15, Chad closed its border with Sudan. It later announced that it had received more than 320 defecting Sudanese military soldiers who fled the violence inside its territory.

N’Djamena reported last Wednesday that the soldiers of the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) had fled to Chad on Sunday after the eruption of the clashes between the SAF and RSF. They had crossed the border and surrendered to the Chadian army.

In a press conference, Chadian Defence Minister General Daoud Ibrahim said that the Sudanese military “entered our lands”. “They have all been disarmed and sheltered.” He added that “those who surrendered to our forces are 320 members of the Sudanese Armed Forces, from the gendarmerie. “The situation in Sudan is worrying and deplorable, we have taken all the necessary measures in the face of this crisis,” the minister said.

In the press statement on Wednesday, the defence minister stressed that this war “does not concern” Chad. “It is between the Sudanese, and we must remain vigilant against all eventualities.” In January, Chadian President Mahamat Déby received both SAF Commander Lt Gen Abdelfattah El Burhan and RSF Commander Hemeti, one day after the other, in N’Djamena with the aim of displaying an air of neutrality.

Chadian tribal tensions

French newspaper Le Monde reported that the Chadian authorities are not officially taking sides in this war but that they are clearly leaning to one side. “We are on the side of the institution,” a high-placed source told the news outlet. “The government is keeping silent because the situation is still uncertain, but for us the seizure of power by an irregular force in which many Arabs from the Chadian-Sudanese border find themselves would be a threat to our stability”, detailed another source at the Chadian presidency.

The RSF commander, who was also part of the Janjaweed militias that terrorised Darfur, has solid connections to Chadian elites and important networks in the country. President Déby’s private chief of staff is a direct cousin of Hemedti, for example, and his Rizeigat clan moved to Darfur from Chad. The Rizeigat are part of the Baggara Arab nomads.

According to Le Monde, there is a fear within the Chadian authorities that a victory for the RSF will strengthen political and military ambitions within the large Chadian Arab community. It is feared that the powerful militia leader will promote the rise of his Rizeigat clan if he comes to control Sudan, to the detriment of the Zaghawa, a non-Arab African nomadic herding tribe based in Chad and Darfur, who have constituted the heart of Chadian power for over 30 years. “The biggest challenge for us is the Arab equation. Many of our brothers here are with him and if he were to win, they think they will be supported and armed,” another member of the state apparatus explained to Le Monde.