Gaffar Mohammud Saeneen and Eric Reeves, Co-Chairs

Julie Darcq, Online Campaign Coordinator

Nancy Reeves, editor and financial facilitator

Overview (Eric Reeves)

August has been a grim month in the long history of ethnically-targeted violence in Darfur, with notable atrocity crimes committed against numerous African/non-Arab farms and farmers in the areas to the west and southwest of El Fasher—very close to Zamzam IDP camp. In fact, given the absence of human rights reporting in Darfur, the counselors of Team Zamzam have become key witnesses to the renewed onslaught of killing, rape, looting, and burning of villages. Their testimony was cited in one of the very few Western news dispatches that has attempted to render something of this renewed cycle of genocidal destruction in Darfur: The Times of London, August 12, 2021: “Janjawid returns to spread terror in Darfur after Sudan Revolution.”

A detailed account of what has been witnessed by the intrepid counselors of Team Zamzam appears in the Annex to this update. So, too, do representative responses from camp leaders about the lack of protection and the most basic humanitarian services. It is clear than not only in Darfur but throughout Sudan, people are disgusted with the lack of change in their lives and have largely given up on the nominally civilian government of Prime Minister Hamdok. The recent appointment by the Hamdok government of Minni Minawi has generated fierce disappointment and anger: Minawi, formerly leader of a rebel group, signed the disastrous 2006 Darfur Peace Agreement and went into the government of al-Bashir as a “Vice President.” He is widely viewed by Darfuris an expedient and ambitious man who has no capacity for leadership or even compassion.

Despite the intensely dismaying news from Darfur, where violence may very well increase with the fall harvest season, Team Zamzam has continued to perform extraordinarily in providing assistance to victims of sexual violence and in distributions of basic supplies to the very most needy in the camp and surrounding rural areas. Because the counselors are in such frequent contact with such a range of people throughout the camp—and indeed in accessible rural areas—an additional expenditure was made this month to vaccinate all 20 counselors. Prices for Covid-19 vaccines in Darfur are astronomical by local standards ($120/vaccination), but we believe that Team Zamzam comprises key front-line health workers, as well as critical examples to the people of the camp (including in the wearing of masks and use of sanitizing soap).

The efforts of these women are playing what now appears to be a catalytic role in harnessing the human resources in Zamzam camp that have so long been squandered. An especially revealing testimonial received this month suggests just how this is occurring:

Testimonial of Fatima Mahayaeldain, 27 years old

(This account has been edited for length; the full testimonial can be found in the Annex update)

“I was diagnosed with traumatic fistula at the beginning of 2018. At first I thought I would not survive, as everyone around me started to avoid meeting me, as if I were suffering from something contagious. Here in Darfur, words can spread as quickly as fire in dry straw, and people started to make their judgments before knowing the truth.

“This situation has brought nothing good but more anxiety and stress to my mother and siblings. I stopped going out to interact with people for nearly two years, and my mother was drained by the emotions of shame, as if the illness was her fault. Last year, after my mother had begged many relatives to lend her some money, we went to see a doctor. He said this was a curable fistula that could be treated with a light operation and medication. But after staying two weeks in the clinic, we run out of money and left halfway through the treatment.

“Several weeks later after leaving clinic, the pain has gradually returned, haunting me with stress and sleep deprivation for many months. I felt less pain this past winter, but the stress didn’t leave me.

“Two months ago I met the sisters from Team Zamzam, who came to pay me visit after my mother had contacted them. In the beginning I did not really feel hopeful that I had any chance of recovery from this illness, after losing so much hope and weight together. The sisters in our first meeting registered my name and talked to me for about an hour and half, listening intently. Since our first encounter, they have never stopped seeing me—and three weeks ago they surprised me with the news that I would be going to the clinic for treatment.

“Each time they come to see me for talk, my mood would instantly change for good afterwards. Their words had very strong effects on me. Their words can awake any bleeding heart. The sisters made me feel strong and positive about myself and this had even positive impact on my mother who is look happier than ever. I now feel much better, the pain is disappearing, I sleep well in the night, and my mood is raised.

“Through the sisters, I have met new energetic friends and many other young sisters who went through a similar situation in the past. And with the help of sisters, some of us have now created a new volunteering group through WhatsApp (called “Sisters for Change”), aiming to help even more girls and women. Here in this camp and in the other camps in most of Darfur there are many thousands of young girls suffering from similar [sexual violence] in total silence. The stigma attached to this illness is so unbearable and the physical pain is so debilitating. Social isolation is dispiriting and its psychological impact is exhausting.

“Today I want to become involved as much as possible as volunteer to help those who are voiceless. I cannot find words to thank the sisters of Team Zamzam for their efforts and their help, but I will my best to pay my debts of gratitude.”

[What is a fistula? See the brief account here.]

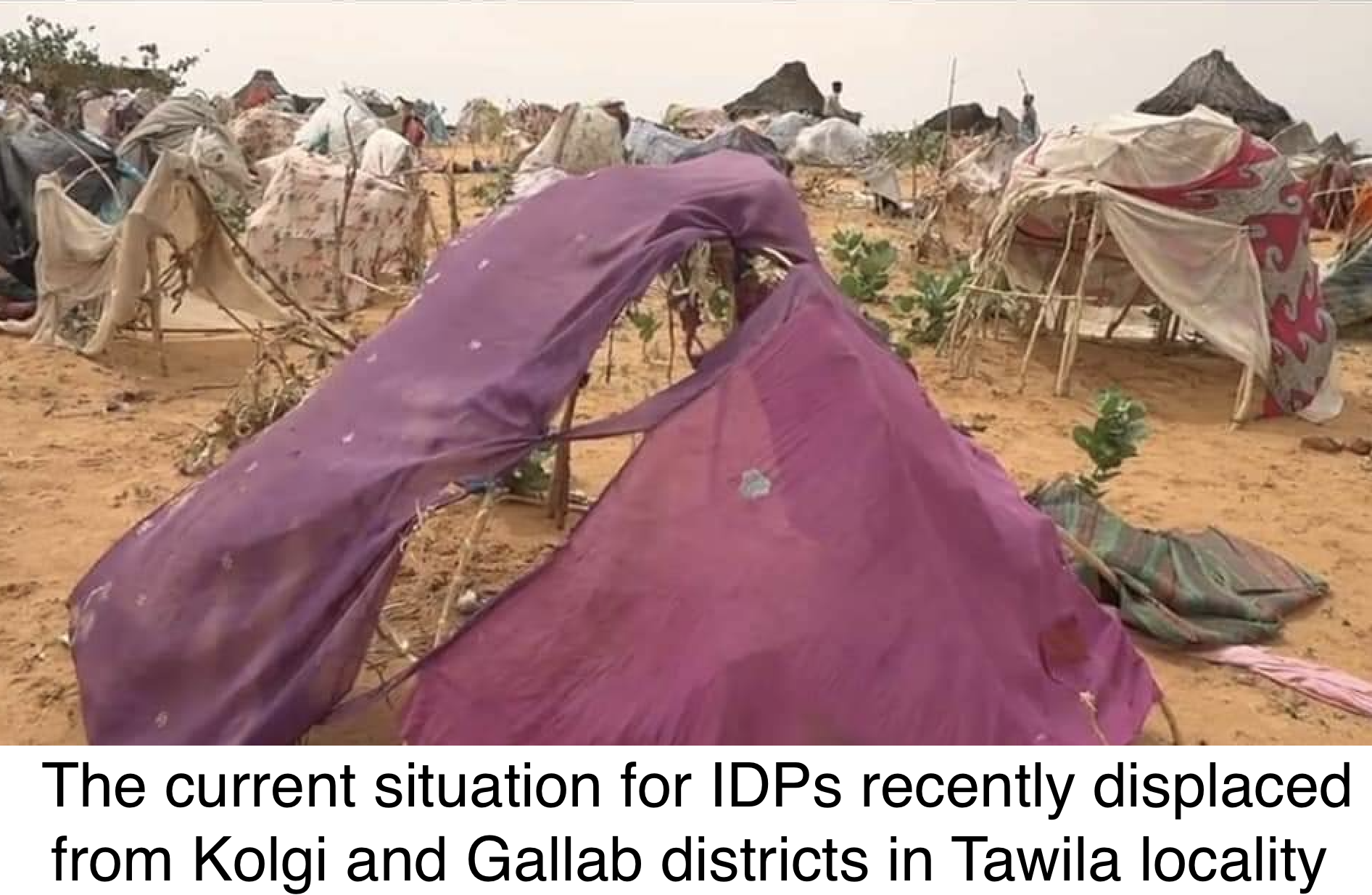

But recent violence threatens all that has been accomplished to date: there have been numerous brutal rapes of girls and women, and large populations of newly displaced persons are arriving daily in Zamzam:

Counselors are presently responding to the needs of a number of girls and women in one area who were all raped earlier this month (primarily girls). But the sad truth is that most rapes will never be reported, nor will treatment be accessible. And even those who set up primitive shelters in Zamzam are far from secure.

The coordinating counselor for Team Zamzam reported that the number of victims from the attacks on the villages in the area of the Golgai attacks exceeded twenty. The youngest one is nine years old and so far victims came forward to speak to the counselors. In one location, three young sisters from one family, along with their cousin and others, came forward to share their horrors. Their names are:

[1] Nafisa Musa Tirab, 17 years old (Mir-shing village)

[2] Farhat Musa Tirab, 14 years old (Mir-shing village)

[3] Galia Musa Tirab, 18 years old (Mir-shing village)

[4] Habiba Adam Tirab, 18 years old (Mir-shing village)

[5] Mariam Lalil Baraka, 47 years old (Arba Beyout village; Arba Beyout literally means the village of four houses).

[6] Khadiga Youssif Mohamed, 20 years old (Hashaba village)

[7] Howa Mohamed Yahya, 23 years old (Kolgi village)

[8] Oumima Idriss Tahier, 21 years old (Zonuba village)

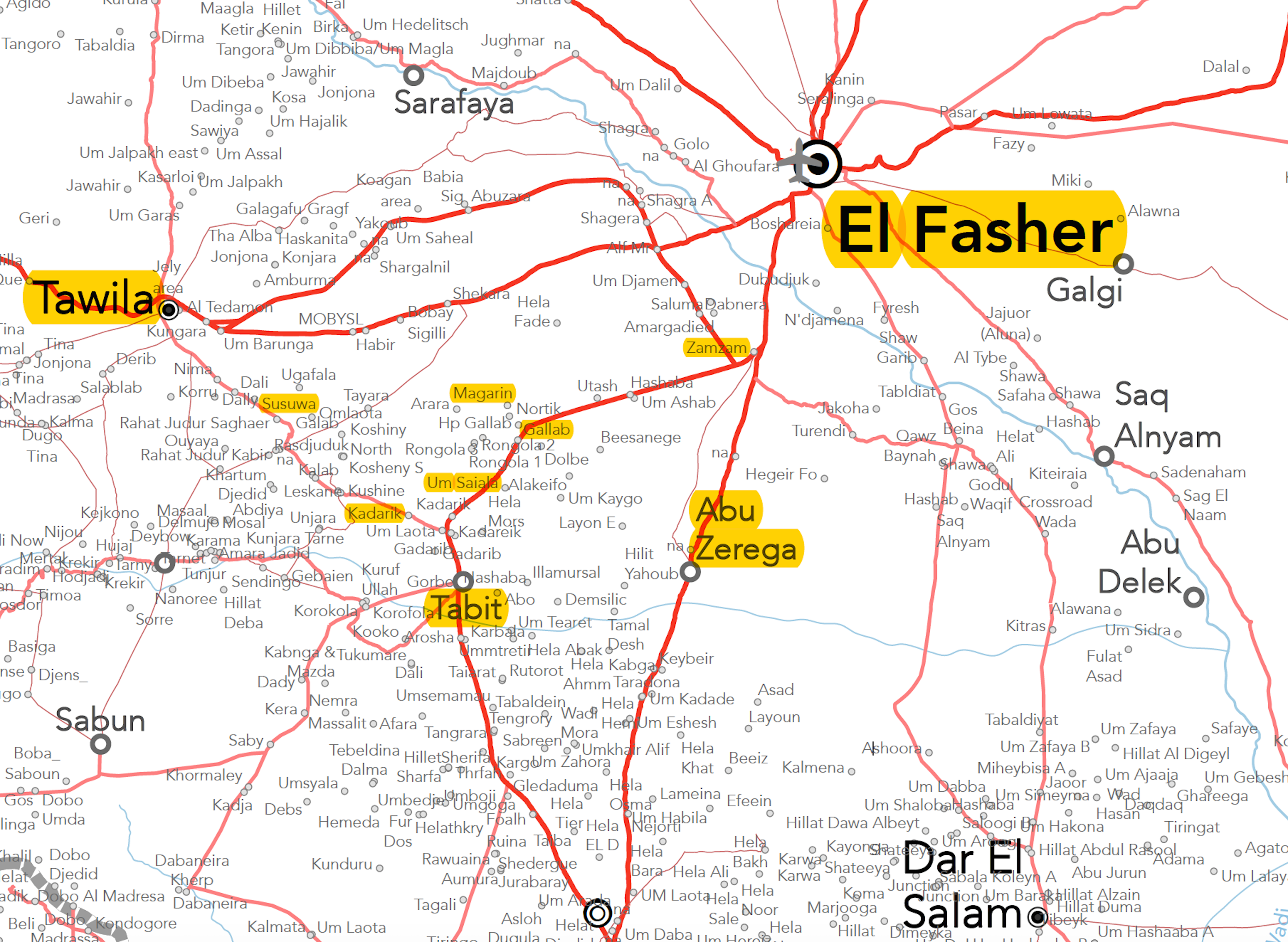

This map represents an approximately 90 square kilometers of territory in North Darfur that has seen terrible violence this rainy season—with almost no international response or even reporting

One survivor of sexual assault offered this searing account to the Team Zamzam counselors. It is, among other things an explanation of why girls and women find themselves so vulnerable to sexual violence—and how decisively this violence is racist in nature.

From Galia Musa Tirab:

“With my two sisters and my cousin, I went to the village of Mir-shing in Kolgai locality to work in agriculture for a monthly wage. When we arrived there at the beginning of the month, we found a job in agriculture on a farm belonging to a resident of El Fasher, and we agreed with him to work on his farm for a monthly salary. We started cleaning and preparing for planting. The farm owner brought us food, supplies, and other living necessities for two weeks and went back to El-Fasher. No one told us the danger of the situation in this area, and even the owner of the farm did not tell us anything when he left us and went to El Fasher.

“During our weeks in the farm, all we have been hearing are scary stories from our neighbouring farms. But the day before they attacked us, we heard nonstop gunfire from nearby.

“I thought many times of taking my sisters back to El-Fasher, but the problem was that if we returned before we finished our work, the owner would not pay us anything—and we had left our mother in Zamzam without anything. After hearing the gun firings in the previous day, the next morning we were attacked around 10 o’clock while we were just about to start our daily labor. The attackers appeared suddenly on the backs of many camels, on horses, and on motorcycles. They surprised us, yelling, screaming, and firing. When we realised this, we were already surrounded on all sides by as many as thirty men. They were young men, with only a few grey-haired elderly men.

“After we were surrounded, some of the attackers immediately left us and started chasing other people of neighboring farms, who were fleeing in panic. After this, about eight of them got off from their camels and motorcycles to tie us up with ropes at gunpoint. From there, they took us for about a one-hour walk and all this time they kept whipping us on our backs, screaming on our faces and insulting us with bad racial slurs. [Hurling of racial slurs and epithet has been a defining feature of sexual assaults on African/non-Arab girls and women in Darfur from the very beginning of the genocide—ER]

“After taking us to their place, we were separated from each others and they started asking questions, such as where the men of these villages have gone, which tribes we belonged to, did we love Arabs or hate them—and then after this they began to do bad things on us. I tried to resist but they knocked me down and ripped my clothes. After this, all I remember was hearing the screaming of my sisters and my cousin. Besides the bad things, they took many of our photos with their cellphones while they were on top of us.

“We were whipped on our backs, racially abused, and endured many slaps on our faces. After three hours of humiliation and ordeal, they released us and told us not to think of saying anything to anyone about them; and if we did say anything about them, no one would do anything in this country. They told us that they would haunt us even in the camps if necessary. For ten days, I didn’t want to say anything about what happened to us, this because I’m afraid of them; but after talking to my sisters from Team Zamzam now I feel slightly better. My youngest sister, however, is still suffering from pain and terrible nightmares.

“Talking to my sisters from Team Zamzam made me feel strong, more relieved of the stress and positive about my future. I might get through this one day even though I still doubt if I can forget the nasty racial slurs.”

Many thousands of girls—some as young as seven or eight years old—have been raped during the ongoing Darfur genocide

Distributing relief supplies while still conducting psychosocial counseling and providing care for fistula patients will be a major task for Team Zamzam in September, with the added challenge of assessing who among the many are most in need of food and medicine.

But it is important to recognize the scale of achievements during this difficult month. Of particular note are the seven successful fistula surgeries, surgical interventions that are quite simply live-changing and life-saving:

Mariam El-Dai Ahmed, 22 years old

Rania Ali Bahareldain, 17 years old

Rougia Mohamed Ali, 19 years old

Farhat Hussein El-Tayeep, 24 years old

Fatima Mahayaeldain, 27 years old

Manal Musa Abdulrahman, 22 years old

Ayida Abakar Kamis, 23 years old

Team Zamzam also distributed supplies to many hundreds of the IDP camp’s most destitute residents, and conducted individual and group psychosocial therapeutic sessions for hundreds of traumatized girls and women.

The women of Team Zamzam continue to demonstrate truly extraordinary commitment, solidarity, compassion, and skill. They are now among the most important front-line health workers in Darfur.

*****************

A fuller account of both the military/political situation in North Darfur—as well as the distributions of supplies and counseling sessions conducted hat has been accomplished this month in the face of growing challenges—is detailed in the ANNEX to this update.

Previous updates are archived at | https://www.ericreeves-woodturner.com/blog/

To provide help for our project, see | https://www.ericreeves-woodturner.com/gallery