Annex to August 28, 2021 Update: Responding to Sexual Violence in Darfur

From the Team Zamzam coordinator, August 2021 (a note of gratitude from the coordinator appears at the end of this Annex)

• Current humanitarian situation:

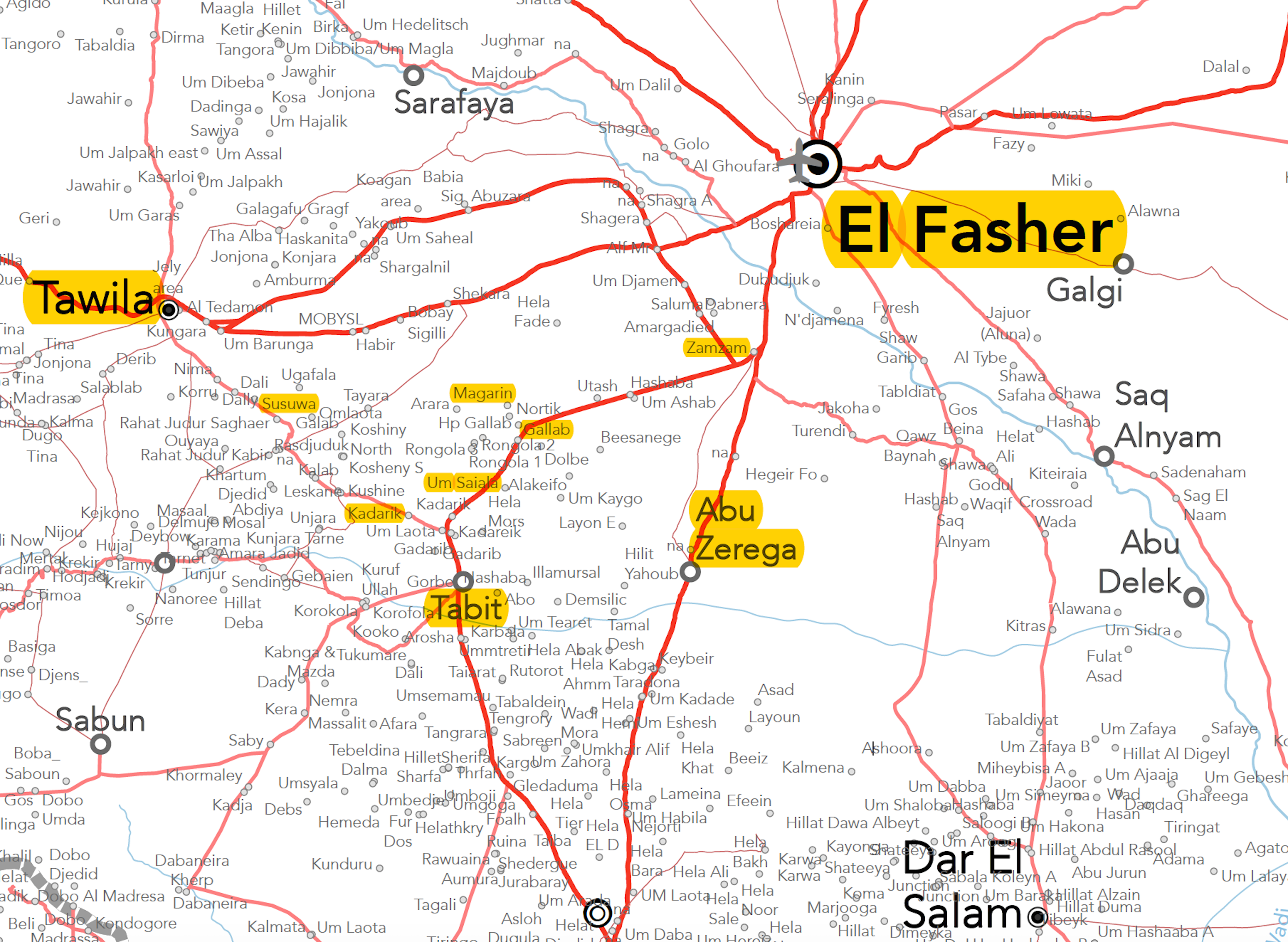

Despite repeated calls by camp inhabitants, the living conditions in Zamzam are still going from bad to worse, with the recent waves of mass displacement from the Galab area [west/southwest of El Fasher—see map below]. Several hundred of the most vulnerable groups—impoverished families, widows with children and single mothers—have been going without proper nutrition and clean water for many days since they were displaced.

This difficult reality has pushed many of the families to send their children to El Fasher market to beg in the streets and wealthy neighbourhoods to fetch daily nutrition. The vast majority of those fleeing from the inferno of recent attacks are in fact from the poorest groups, and their livelihoods depend on daily labor on farms for monthly wages or a share of what is produced. Most of these poor families, even before the planting season began, earned their meager living by means of daily labor in brick-making industries on the outskirts of El Fasher and other daily work, such as cleaning homes and restaurants. But the rainy season stopped the brick-making and work in the city became difficult; this has forced people to search for an alternative in the agricultural sector.

• The feeling of disappointment and loss of confidence in the so-called the “revolutionary Government”

From the day of their displacement until this day, no government official from the state or the governor’s office has stood before the displaced to see their miserable humanitarian conditions. No government officials at higher levels have come to see them, listen to them, or to find out what happened to them—let alone providing humanitarian assistance. One of the fleeing sheikhs said, “We have lost confidence in Hamdok’s government; we have lost confidence in the state government; and we have lost confidence in all government officials in this country.”

The sheikh continued, “How do we trust these people? These people are good only for lies and false promises. And now they are celebrating the arrival of a general governor of Darfur in El Fasher [Minni Minawi], while we are appealing for urgent protection from the Janjaweed and families are struggling for daily necessities.”

Another sheikh said, “We don’t trust anyone anymore and we want the international community to provide us urgent protection, and to bring back all those good humanitarian organisations which were expelled from Darfur by the former regime.” And he continued, “After what happened to us during recent killing, looting, burning, and rape, they want to tell us that a committee has been set up to investigate what happened. This is joke and a blatant insult to our dignity.” The sheikh concluded: “They set up a committee that is closely linked to the perpetrators of these atrocities and they want us to accept it.”

• Assessment by the coordinating counselor of the current situation, August 1 – August 12:

The humanitarian situation is deteriorating, with an increasing number of people fleeing the inferno of the recent attacks—from Koli, Gallab, and the neighboring villages of Tawila locality.

On the second of August, after we [Team Zamzam] heard about the deteriorating humanitarian situation resulting from the attacks by Janjaweed militias on villages, six counselors accompanied by two security guards went to the outskirts of the Gallab area where the events had been taking place since the end of July. After we had assessed the situation from a close distance and gathered many testimonies from those fleeing, we returned to El Fasher, and from there we headed to Zamzam camp immediately to provide urgent basic necessities for a number of families in the most vulnerable categories.

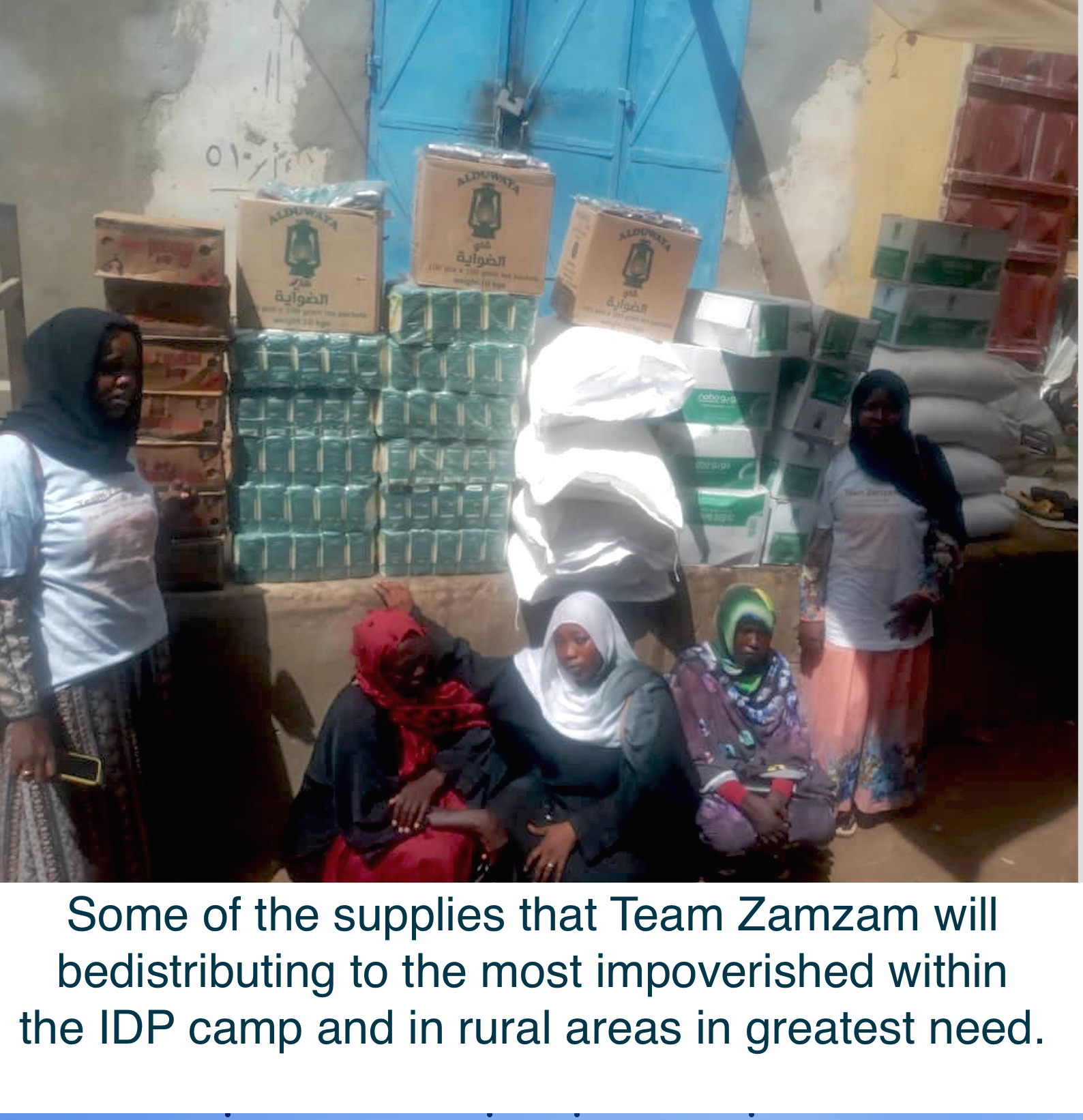

Basic necessities provided/distributed included: pasta, sugar, rice, cooking oil, and baby milk

• The beneficiaries of this round of distribution, as of August 12, 2021:

Totals for Zamzam camp, sections A, B, C, and D

113 families

42 single mothers with 83 children

Total persons benefited : 817

Other essential necessities:

38 boxes containing women’s cotton, toothpaste, shaving razors and shaving cream

2 boxes of antibiotics and anti-depression medication

therapeutic art supplies.

Beneficiaries:

Beneficiaries:

58 victims of sexual violence.

29 patients with fistulas were provided medicines

27 persons benefited from art supplies/materials

Counseling sessions:

47 group counseling sessions in Zamzam camp, sections A, B, C and D

127 individual counseling sessions in Zamzam camp, sections A, B, C and D

Total number of sessions: 174

Fistula Surgeries for August 2021:

[1] Mariam El-Dai Ahmed, 22 years old

[2] Rania Ali Bahareldain, 17 years old

[3] Rougia Mohamed Ali, 19 years old

[4] Farhat Hussein El-Tayeep, 24 years old

[5] Fatima Mahayaeldain, 27 years old

[6] Manal Musa Abdulrahman, 22 years old

[7] Ayida Abakar Kamis, 23 years

[Further details on August distributions will appear in the September update: internet and telephone connections in Darfur have been especially poor of late.]

******************************

But we continue to hear terrible accounts of new sexual violence and brutal displacement of farming civilians. The voices of the women in the following narratives tell us far too much about realities in Darfur and the failure of the government of Sudan and the international community to respond to such acute suffering.

From Galia Musa Tirab:

“With my two sisters and my cousin, I went to the village of Mir-shing in Kolgai locality to work in agriculture for a monthly wage. When we arrived there at the beginning of the month [July], we found a job in agriculture on a farm belonging to a resident of El Fasher, and we agreed with him to work on his farm for a monthly salary. We started cleaning and preparing for planting. The farm owner brought us food, supplies, and other living necessities for two weeks and went back to El-Fasher. No one told us the danger of the situation in this area, and even the owner of the farm did not tell us anything when he left us and went to El Fasher.

“During our weeks in the farm, all we heard were scary stories from our neighbouring farms. But the day before they attacked us, we heard nonstop gunfire from nearby.

“I thought many times of taking my sisters back to El-Fasher, but the problem was that if we returned before we finished our work, the owner would pay us nothing—and we had left our mother in Zamzam without anything. After hearing the gun firings in the previous day, the next morning we were attacked around 10 o’clock while we were just about to start our daily labor. The attackers appeared suddenly on the backs of many camels, on horses, and on motorcycles. They surprised us, yelling, screaming, and firing their weapons. When we realised this, we were already surrounded on all sides by as many as thirty men. They were young men, with only a few grey-haired elderly men.

“After we were surrounded, some of the attackers immediately left us and started chasing other people of neighboring farms, who were fleeing in panic. After this, about eight of them got off from their camels and motorcycles to tie us up with ropes at gunpoint. From there, they took us for about a one-hour walk and all this time they kept whipping us on our backs, screaming at our faces, and insulting us with bad racial slurs. [Hurling of racial slurs and epithets has been a defining feature of sexual assaults on African/non-Arab girls and women in Darfur from the very beginning of the genocide—ER]

“After taking us to their place, we were separated from each others and they started asking questions, such as where the men of these villages have gone, which tribes we belonged to, did we love Arabs or hate them—and then after this they began to do bad things to us. I tried to resist but they knocked me down and ripped my clothes. After this, all I remember was hearing the screaming of my sisters and my cousin. Besides the bad things, they took many of our photos with their cellphones while they were on top of us.

“We were whipped on our backs, racially abused, and endured many slaps on our faces. After three hours of humiliation and ordeal, they released us and told us not to think of saying anything to anyone about them; and if we did say anything about them, no one would do anything in this country. They told us that they would haunt us even in the camps if necessary. For ten days, I didn’t want to say anything about what happened to us because I’m afraid of them; but after talking to my sisters from Team Zamzam I now feel slightly better. My youngest sister, however, is still suffering from pain and terrible nightmares.

“Talking to my sisters from Team Zamzam made me feel strong, more relieved of the stress and positive about my future. I might get through this one day even though I still doubt if I can forget the nasty racial slurs.”

• Many cases of trauma, nightmares and severe depression among young girls

Since the beginning of the events in the Galab area, many new victims have come to attend the private sessions, and among them are a considerable number of young girls, most of whom are still in a state of shock—terrorized by the events that have taken place in the areas southwest of El Fasher since the end of July. These young girls complain about lack of sleep, nightmares, hearing the voices of their attackers in the night, and hearing gunshots. The features of shock and fear are visible in their frail faces; we are now working with them and counseling on a case by case basis, trying to provide the best possible psychological therapy we can.

Even though most of them find it hard to speak exactly about what happened to them, we believe that there is strong evidence to suggest that they have suffered serious assaults. From counseling sessions we have been able to extract several testimonials, which indicate specifically that sexual assaults took place at several places in first days of the attacks.

• The terror of Janjaweed and the policy of land occupation, intimidation, and bullying

Testimonial of Khamisa Mohamed Ishag, 29 years old, seven months pregnant originally from Kolgi

“At the beginning of July, we were getting ready to go to our villages for farming before the first drops of rain. Most of the neighbors, both relatives to friends, were very excited about the idea of going back to our villages after several years incarceration as IDP’s in Zamzam camp. I had not been optimistic about going back, but since everyone was talking about the prospect of real peace brought by Juba Peace agreement, I finally decided to give it a try with my neighbors.

“On 13th of July, I packed our few possessions on the back of our donkey to head to the village with my three children alongside, as well as others who were going to the same village. On our arrival, we were shocked to find most of our farms had been taken over by new settlers—Arab nomads whom we never seen in this area before. After this, our sheik went to see the people who returned from the same camp to the village a few weeks before us and they told him that this is the reality in this area nowadays. And anyone whose farm has been taken by the new settlers has no choice but to negotiate with them. The Arab nomads demand two-thirds of all agricultural production if we want to avoid confrontation and conflicts.

“After this, the sheik said he has no any power to do anything nor would the police in Tawila do anything against these people.

“After this, some of the families who found their farms occupied by new settlers decided to return to the camp, but we decided to stay there to work in some small rocky spaces that had been left over; and despite the difficulty of such farming, we stayed there to work until the attack that was to come.

“Since our arrival we had been hearing and seeing attacks on farmers by new settlers on a daily basis. We experienced constant deliberate provocations, intimidation, and hateful, humiliating racist abuse. They said they did not want us to stay in our villages without giving back something to them.

“Our sheikhs and other community leaders had warned us since we arrived that the Arab settlers would attack us. On July 28 or 30—at the end of last month, I’m not sure about the date but it was early morning of Friday [July 30]—the attacks began while we were asleep. The day before the attacks, there was tension in the area between the nomads and the farming communities who were fed up with the provocations. I think everyone was a sleeping on alert.

“Very early in the morning, about one hour after fajr prayers (alāt al-faǧr, or “dawn prayers), I heard screaming voices close by from the north of our village. At first I first thought it might be something normal, but my doubts quickly increased. I immediately woke my children and mother-in-law, who was staying with us. After this, about three minutes later, we realised that we were under attack when we saw a mass of people fleeing and running in panic.

“In that chaotic moment of terror and panic I said to my mother-in-law, “take the children and run as fast as you can toward the location everyone was running to.” After this, I stayed inside my makeshift tent for several more minutes, searching for water to take with me. I eventually left the tent heading towards where people had run away to escape .Looking back all I could hear was screaming everywhere, blazing gunfire from a near distance, and more people running as fast as they could. I couldn’t run as the others, so I kept walking as fast as I could while many people passed me by.

“After walking for nearly half an hour, I was slammed down from behind by a person who was riding a camel or horse. I couldn’t see what it was, but its force was that of an animal—I think it was camel. I was knocked unconscious to the ground and all I see could see was a blurry picture of a group of masked people looking directly on my face. I heard the voice of a man saying, “This one is done; we will come back to her later.” I again lost consciousness. I must have lain there for several hours until wakened by up the heat of the sun. When I woke up, it was almost mid-day, and no one seemed to be in the area. I got very scared, my heart was beating faster and all I was thinking of was my children.

“Totally disoriented, not knowing which direction I should I take, I kept walking for about three hours without water, in exhaustion, confusion, fearing being run down again—and worried about my children. Finally, by the time I saw someone in the distance, I was on the verge dying. I couldn’t care less whether they were Janjaweed militias looking for me—or my own good people. I went directly to them and thank god it turned out to be the people who fled early in the morning. Thank god my children and members of family managed to escape unhurt. But there are many people—some of them are our neighbours and relatives—who still have not reunited with their missing loved ones. It’s a horrific situation, but in God’s grace we managed to get through—and one can wish a speedy recovery for those who were hurt too much.”

More on political attitudes about Darfuris: Janjaweed provocation, fear of police from Janjaweed militias and absence of the state control

Testimonial of Majida Ibrahim xxx, 37 years old—a midwife and influential member of a secret network of women (Shabaka means network)

“We’re fed up with this crazy situation, we are tired of listening to these stories of ‘investigation committees’ whenever there are attacks on citizens; and we are tired of the repeated insults against women. Every one of us in Darfur knows who the Janjaweed are, and everyone here in Darfur and Sudan knows the Janjaweed. Why all this hypocrisy and cowardice? Why this refusal to tell the truth? Why are people burying heads in the sand?

“Today most victims in Darfur have lost all hope for state institutions like the police. When victims go to the police to make complaints on any potential crimes, the first thing the police ask is the identity of the perpetrator. And if it turns out to be someone from one of the nomadic Arab tribes, they will simply tell you that they can’t do anything. This is the disgusting reality that has been going on in this country for years. Some may try to avoid facing these realities, but there can be no escape until something meaningful is done.

“These days some people are trying hard to portray what happening in Galab, Kolgi and Tawila as tribal conflicts; but how they need to explain the following facts:

• How does a simple nomadic person, who lives on the back of his camel, own a sniper rifle and rocket-propelled grenade?

• How is it possible for simple nomads, whose livestock is worth only a few thousand dollars, regularly to move around in 4×4 land cruisers, coming from cities like El Fasher, Nyala, and others to make their living?

• How many of these 4×4 land cruisers are owned by simple citizens?

“We have seen many recent victims whose memories of the events are still fresh and most of them can easily identify attackers. The violent humiliation of people won’t stop in Darfur until the last firearm has been taken from all nomadic Arabs in Darfur.”

Testimonial of Fatima Mahayaeldain, 27 years old (full testimonial)

“I was diagnosed with traumatic fistula at the beginning of 2018. At first I thought I could not survive, as everyone around me started to avoid meeting me, as if I were suffering from something contagious. Here in Darfur, words can spread as quickly as fire in dry straw, and people started to make their judgments before knowing the truth.

“This situation has brought nothing good but more anxiety and stress to my mother and siblings. I stopped going out to interact with people for nearly two years, and my mother was drained by the emotions of shame, as if the illness was her fault. Last year, after my mother had begged many relatives to lend her some money, we went to see a doctor. He said this was a curable fistula which could be treated with a light operation and medication. But after staying two weeks in the clinic, we run out of money and left halfway through the treatment.

“Several weeks later after leaving clinic, the pain has gradually returned, haunting me with stress and sleep deprivation for many months. I felt less pain this past winter, but the stress didn’t leave me.

“Two months ago I met the sisters from Team Zamzam, who came to pay me visit after my mother had contacted them. In the beginning I did not really feel hopeful that I had any chance of recovery from this illness, after losing so much hope and weight together. The sisters in our first meeting registered my name and talked to me for about an hour and a half, listening intently. Since our first encounter, they have never stopped seeing me—and three weeks ago they surprised me with the news that I would be going to the clinic for treatment. Since I began seeing the sisters they have come to visit me regularly; they talk to me at least four times a week, and sometimes they even call me on phone to talk at length.

“Each time they come to see me for talk, my mood instantly changes for good afterwards. Their words have very strong effects on me. Their words can awaken any bleeding heart. The sisters made me feel strong and positive about myself and this had even positive impact on my mother who is look happier than ever. The sisters had not only made me feel better about myself, but they even managed to change the attitude of my friends who used to avoid me constantly. I now feel much better, the pain is disappearing, I sleep well in the night, and my mood is raised, and I’ve begun to understand better the naivety of people passed their judgment on me before knowing anything.

“Through the sisters, I have met new energetic friends and many other young sisters who went through a similar situation in the past. And with the help of sisters, some of us have now created a new volunteering group through WhatsApp (called “Sisters for Change”), aiming to help even more girls and women. Here in this camp and in the other camps in most of Darfur there are many thousands of young girls suffering from similar [sexual violence] in total silence. The stigma attached to this illness [i.e., fistula] is so unbearable and the physical pain is so debilitating. Social isolation is dispiriting and its psychological impact is exhausting. The depressing part of this is that when people hear that someone is suffering from this pain or illness, they look at you as if it’s your own fault. In fact, all this was caused by the bad things that occurred between bushes and corridors of houses without one’s consent [sexual assault]. Everyone knew of this reality, but they just wanted to blame the victims.

“Today, I don’t want to talk about what caused my pain, but everyone will come to know the truth. The good news is that fistulas can be treated, and I want to become involved as much as possible as a volunteer to help those who are voiceless. I cannot find words to thank the sisters of Team Zamzam for their efforts and their help, but I will my best to pay my debt of gratitude.”

This map represents an approximately 90 square kilometers of territory in North Darfur that has seen terrible violence this rainy season—with almost no international response or even reporting

This map represents an approximately 90 square kilometers of territory in North Darfur that has seen terrible violence this rainy season—with almost no international response or even reporting

A message from the leaders of Team Zamzam:

Praise and appreciation for the project’s contributors, from Team Zamzam

We in Team Zamzam have learned from the determination and endurance of Darfuri women and girls the value of perseverance and the importance of dedication.

We the counselors draw our inspiration from their stories of struggle, and the determination of these resilient and silent victims who, despite their suffering, still are holding onto their dreams. Dreams of better days ahead; dreams of a safer Darfur for all its citizens; dreams of a fairer Darfur for women; dream of less violence; dreams of a state governed by the rule of law; dreams of equality of genders; and dreams of prosperity for their children. We, as first female counselors ever in this camp, share their aspirations fervently and some of us already begun to feel everything is possible if there are enough honorable men to listen to us.

Today we feel grateful and proud of what we have already achieved during the space of one year. Our progress and achievement would not been possible except for those men and women who supported us financially and morally from far away beyond the seas and oceans.

There is still too much work need to be done throughout Sudan—and Darfur in particular; we intend to go forward from village to village, from town to town, and from city to city until we open up every potential avenue leading the women of this country to a better society, one that respect their women. Those who supported our small project should be very proud for contributing to the revival of dying hopes and aspirations of many distressed and traumatised young girls and women of Darfur.

Local Coordinator of Team Zamzam

El Fasher, August 10, 2021