“Watching Sudan’s Economic Bubble Burst”—Four years later

Eric Reeves | September 12, 2018 | https://wp.me/p45rOG-2i8

Exactly four years ago, I published “Watching the Bubble Burst: Political Implications of Sudan’s Economic Implosion” (September 2014 | https://enoughproject.org/files/EnoughForum-WatchingTheBubbleBurst-Reeves-Sept2014.pdf/. (The Executive Summary of this analysis appears below.) Every major conclusion and assessment in the analysis has been borne out by subsequent events: the economy is indeed “bursting.” A dispatch today from Radio Dabanga offers the opinions of Sudanese economists and political analysts, assessing the implications of the conspicuous charade that is the regime “re-shuffling” recently announced by indicted génocidaire and president of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir. This is all self-serving blather that will do nothing to change the fundamental issues crippling the Sudanese economy. One highlight:

Hasan Bashir, Professor of Economics at El Nilein University in Khartoum, [said] “Reducing the number of ministries is a good step, [but] the amount allocated to government spending in Sudan is the largest in the world, compared to the Gross Domestic Product.”

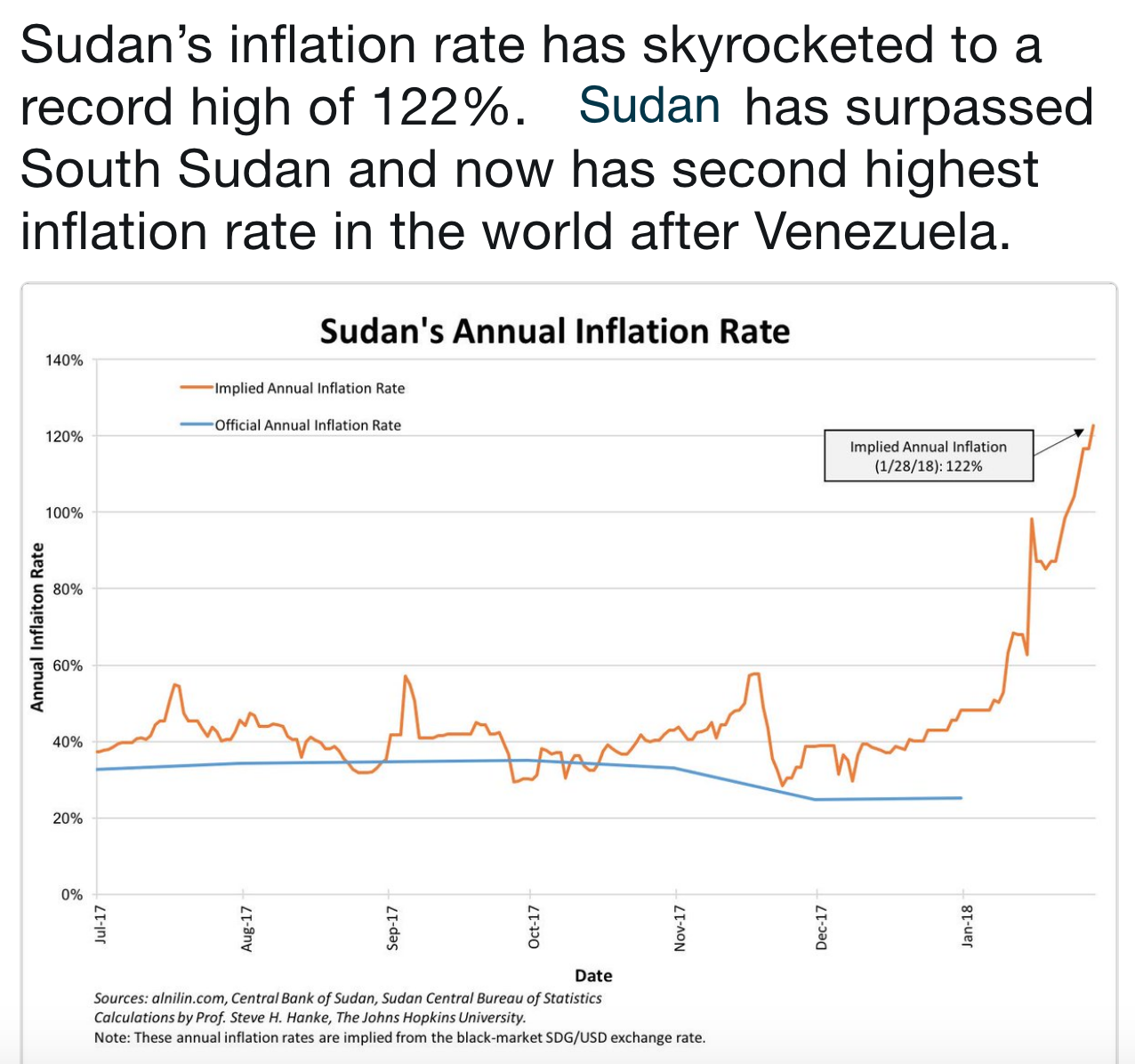

There could hardly be a worse economic indicator and does a great deal to explain why the real inflation rate in Sudan is higher than that of any other country in the world, excepting only Venezuela. Professor Steven Hanke, Senior Fellow and Director of the Troubled Currencies Project at the Cato Institute has this year published an extraordinarily revealing graph for Sudan’s inflation rate:

The suffering caused by inflation—of food prices, pharmaceutical prices, transportation costs, and even the cost of clean water that is pumped using imported refine oil products—is simply incalculable and has produced headlines such as these:

Sudanese rely on starches, cut meals to one a day | Radio Dabanga, September 5, 2018 | KHARTOUM / ED DAEIN

Sudanese in various parts of the country have difficulty in coping with the continuously rising food and consumer goods prices. A number of families told Radio Dabanga that the circumstances forced them to reduce their daily meals to just one. People in Khartoum reported that they eat mostly starches instead of vegetables, meat, and fruit.

Shortages of and astronomical prices for critical medicines have frequently been reported as well.

I repeat my major conclusion of September 2014: the Khartoum regime cannot survive except temporarily and by the most bloody and destructive of means, including economic self-cannibalization.

Sudan: Economists denounce Al Bashir’s “new emergency plans” | Radio Dabanga, September 12, 2018 | KHARTOUM

Sudanese financial experts have downplayed the effects of the reduction of government expenses as announced by President Omar Al Bashir on Monday. In his address to the nation, the president reported the dissolution of the National Reconciliation Government. The ministries are to be reduced from 31 to 21. The number of ministries in the states will be downsized as well. The reshuffle is part of a major plan to combat the crises in the country by “comprehensive political and economic reforms,” he said.

[This re-shuffling is mere window-dressing for an inability to halt economic collapse—ER]

According to Al Bashir, the state has developed “an urgent emergency programme that includes specific projects with direct returns, in order to boost performance and achievements in the macro-economic sectors.” The new programme is expected “to improve the livelihoods of the Sudanese within a defined time.”

[More absurd hot air—ER]

Professor Hamid Eltigani, Head of the Department of Public Policy and Administration at the American University in Cairo, however ridiculed Al Bashir’s economic emergency programme “after nearly 30 years in power.” He described the president’s new plans as “an attempt to market himself in preparation for the general election in 2020” to Radio Dabanga.

“The replacement of minister Ahmed with mister Mohamed can never be a solution to the country’s huge economic crisis,” he commented. [NB] “The structural problems of the country’s economy, related to a very weak production sector, the bankruptcy of most factories, a lack of liquidity, and almost no access to loans, should be tackled instead.”

[Precisely right—ER]

Hasan Bashir, Professor of Economics at El Nilein University in Khartoum, affirmed the weakness of the plans. “The announced measures are economically limited and will hardly have any impact on the Sudanese markets,” he told this station.

“The president’s decisions are limited to the executive authority, while the executive and legislative branches, and the bodies of the ruling National Congress Party require restructuring as well,” he explained. “Reducing the number of ministries is a good step,” the professor added.

[But such “re-structuring” does nothing absolutely nothing to change government spending except in the most trivial of ways—ER]

“The amount allocated to government spending in Sudan is the largest in the world, compared to the Gross Domestic Product.” The Sudan Call described “the new measures of the Khartoum regime” as “movements within the society club called government.”

[An extraordinary distinction for the Sudanese economy, especially since some 70% of that government spending is on military and security sectors—ER]

The change “will not resolve the crisis of living for the Sudanese, nor will it bring peace or stability in the country,” the Sudanese opposition alliance said in a statement on Tuesday. “It is just an attempt to divert the attention … from Al Bashir’s grip and the grip of his family on … the country’s resources.”

The reshuffle of the cabinet is the second one this year. In May, Al Bashir announced a new government as well. A political expert told Radio Dabanga at the time that the changes in the cabinet were an attempt to muffle rising public discontent about the increased taxes and skyrocketing prices in the country.

In his speech on the occasion of Eid El Adha in end August, Al Bashir said that he will drastically review the macroeconomic policies in the country, and adopt new measures to stimulate production, increase exports, and control imports.

[Coming from al-Bashir, these words could not be more vacuous, as the failures of recent years have made painfully clear—ER]

Watching the Bubble Burst: Political Implications of Sudan’s Economic Implosion

An Enough Forum publication by Eric Reeves | September 16, 2014

Executive Summary

Despite very considerable evidence that the economy of Sudan is collapsing under the weight of numerous unsustainable pressures, there is no full extant account of these pressures at this critical moment in the political history of Sudan. Understanding the human and political consequences of economic collapse in Sudan is also critical in making sense of the future of now independent South Sudan. Nominally tasked with monitoring the Sudanese economy, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and to a lesser degree the World Bank, have failed to present a full or accurate picture—too often dancing around difficult issues and simply accepting at face value figures provided by the Government of Sudan. Every one of the eight key charts in the IMF’s July 2014 report indicates as its source of data: “Sudanese authorities and staff estimates and projections.”

Most conspicuously, the two organizations have failed to provide anything approaching realistic figures concerning military and security expenditures. There is in the July 2014 IMF report not a single line item—not one—reflecting or indicating the scale of military and security expenditures. We may learn about “Regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets”; but we will learn nothing about investments in weapons acquisitions from abroad or the growing domestic armaments production. We learn nothing of salaries and logistical expenditures for the Sudan Armed Forces or the militias the government supports. Since the Government of Sudan—essentially the National Congress Party (formerly the National Islamic Front)—is deeply threatened by a fuller understanding of the dire straits in which the economy currently lies, it has an obvious interest in doing what it can to minimize popular understanding of growing economic threats, and in particular the excessive budgetary commitments to the Sudan Armed Forces, various security forces, and militias.

Certainly there is no dearth of studies, statistics, or analyses of the economy (see Bibliography). But none does enough to assess the impact of Sudan’s growing economic distress on various crises within Sudan itself and the region as a whole, most particularly in South Sudan. Continued serious fighting in Darfur, the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan, and Blue Nile mean that the Government of Sudan is obliged to spend inordinate amounts of annual revenues on armaments, soldiers’ salaries, logistics, and the security services that are an integral part of the military power wielded by the government. Estimates vary widely, but the consensus is that significantly more than fifty percent of budgetary expenditures are directed to the military and security services. Moreover, the oil revenues that fueled the decade of economic growth following the first oil exports (August 1999) are now only a fraction of what they have been. This augurs extreme difficulties in negotiating with South Sudan over final boundaries, since many of the contested areas—including Abyei—have significant oil reserves.

In all the regions where fighting is occurring, agricultural production has declined precipitously, creating extraordinary ongoing humanitarian needs. The government has made provision of relief assistance impossible in the most affected areas of South Kordofan and Blue Nile, and for more than a decade has harassed, impeded, expelled, and threatened humanitarian organizations operating in Darfur, where security has become so bad that further withdrawals by organizations are inevitable.

It is in the domestic political arena, however, that the economy is most worrisome for the NCP government. Inflation remains extremely high—and likely a good deal higher than suggested by the figures coming from the Central Bank of Sudan—and the Sudanese Pound continues a rapid decline in value against the dollar. There is exceedingly little foreign exchange currency (Forex), which has led to acute difficulties in financing imports of all kinds, even food and refined fuel for cooking (Sudan’s refining capacity is not sufficient to meet very large demand). Bread shortages earlier in 2013 and 2014 were a direct result of a lack of Forex for purchases of wheat abroad, exacerbated by the increased cost to bakeries of cooking fuel. Looming over the entire economy is the massive external debt, which in August stood at US46.9 billion according to the IMF; the government can neither repay nor service this debt without reforms—economic and political—it has shown itself unwilling to make.

Last September and October, there was a serious, sustained, and occasionally violent public uprising to protest the price increases resulting from the government’s lifting of subsidies for fuel (including cooking fuel). The government response was swift and brutal, with “shoot to kill” orders in place from the beginning of the uprising according to Amnesty International. More than 200 demonstrators were shot to death, and many more wounded; some 800 people were arrested. The figures are likely much higher. Despite the normalcy of IMF accounts of Sudan’s economy, there can be little doubt that it has reached the breaking point; and continued inflation, which may reach to hyperinflation, will—as it has before in Sudanese political history—be the economic force that brings down the government.

The emergence of the National Consensus Forces as a coalition of smaller northern political parties committed to “regime change” is but one sign of growing determination to end the 25-year rule of the NIF/NCP. The “Paris Declaration” between the National Umma Party (NUP) and the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF) is another such sign. The NUP, led by Sadiq al-Mahdi, is one of the two traditional sectarian parties that have long had significant political support. The SRF is a coalition of armed rebel groups from Darfur, South Kordofan, and Blue Nile that is also committed to regime change, by force if necessary.

The current Government of Sudan has no way to respond to both increasing political pressures and the consequences of a rapidly deteriorating economy. As a result, it will almost certainly resist change, with violent repression, for as long as possible; for many of its leaders have been or will be the subject of arrest warrants for crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court, and will have no recourse or avenue of escape once the government falls. They are as a consequence especially dangerous, and the fall of the regime may well be very bloody. The international community should plan now how to assist in the creation of a democratic, inclusive, and secular Government of Sudan, and should be prepared to address some of the most immediate problems, including widespread food insecurity.