NATIONAL & WORLD AFFAIRS

“From nowhere to somewhere,” The Harvard Gazette

by Jonathan Harounoff

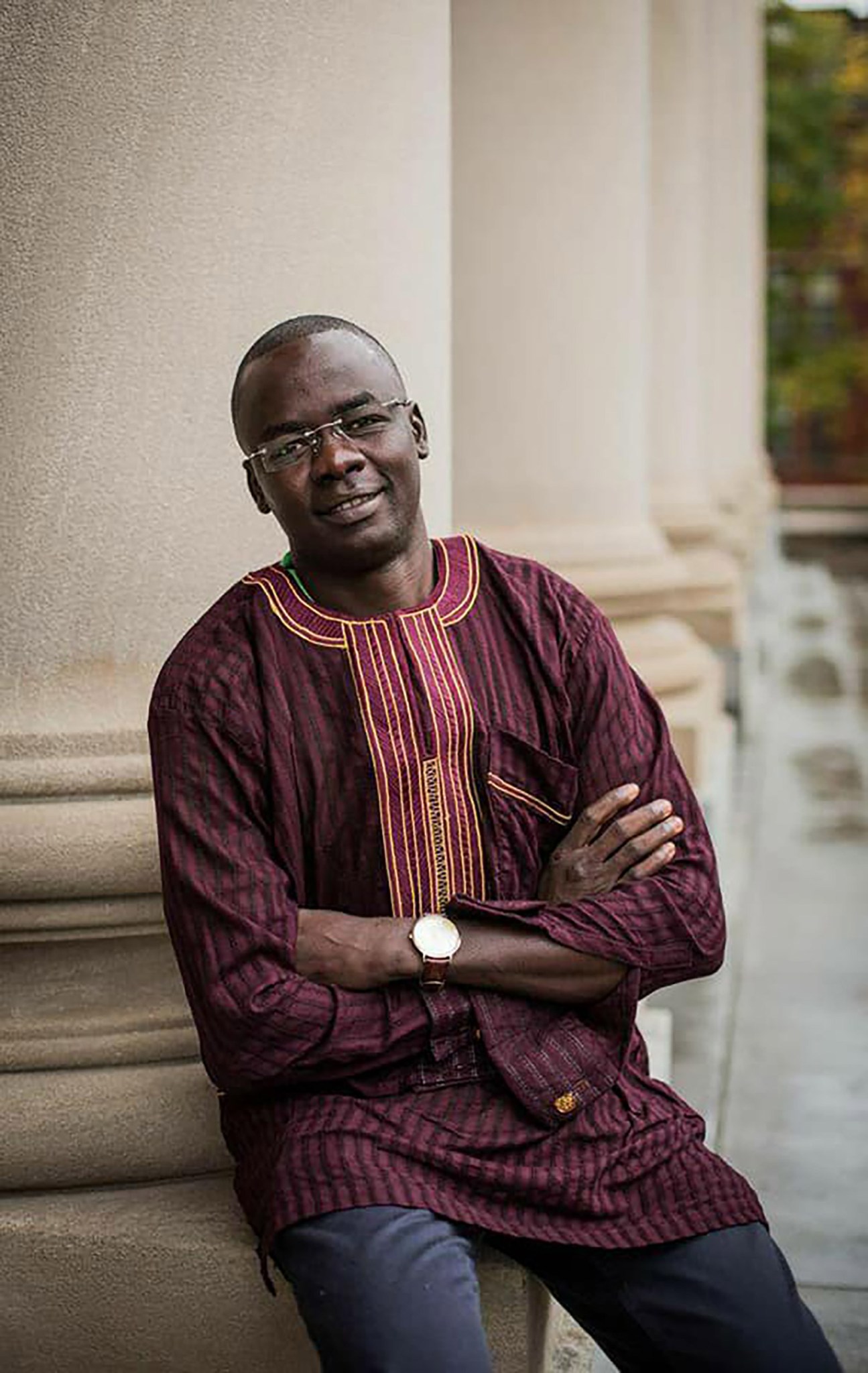

Survivor of Darfur violence comes to Harvard with a mission in mind

AUTHOR’S NOTE: My first encounter with Guy, or Abdelhamid Yousif Ismail Adam, was at a function organized by the Harvard Hillel in mid-April. We talked and I was both shocked and mesmerized by his life story. The next day I met with Guy at Harvard Kennedy School, where I interviewed him for the first of three times. I wanted to write this not just to demonstrate the sheer diversity of Harvard’s student body, but also to bring to light violence that, despite no longer dominating news headlines, continues to rage on.

In order to survive the slaughter in Darfur, it was the promise of education — the bedrock of democracy and freedom — Abdelhamid Yousif Ismail Adam clung to throughout his turbulent youth.

U.N. Security Council estimates show that more than 2.7 million Darfuris have been displaced over the past 18 years. Many Sudanese have fled to neighboring countries — war-torn — to escape the violence and instability of their own.

Adam, who said he changed his name to Guy Josif Adam to honor the people who helped him, is currently studying international human rights law at Harvard’s Division of Continuing Education. This is his story.

Born on New Year’s Day

For Guy (who prefers to use his first name), a birthday celebration is a novel phenomenon. According to his Sudanese passport, his journey “from nowhere to somewhere,” as he puts it, began on Jan. 1, 1986. Yet he does not know the exact date of his birth and believes he is 24 to 26 years old. “The Fur tribe does not keep dates as Western cultures do,” he explained during our first meeting at the Kennedy School.

Sipping a cup of steaming vanilla coffee, Guy began weaving from his painful childhood to the present day in a meticulous, almost rehearsed fluency that made me certain this was not his first interview. His advice to Google “Guy Josif Adam Darfur” if I encountered any biographical questions confirmed this suspicion.

For bureaucratic and official documentation, most in Sudan follow a similar procedure. “If you ask most people in Sudan” Guy jokes, “they will tell you they were born on January 1. It would seem like an amazing coincidence that in the city of Darfur, with over 9 million inhabitants, almost everyone was born on the same day.”

Guy was born in the village of Mara. His parents were farmers who tended livestock and cultivated crops to provide for their seven children. His schooling ended in the fourth grade because his father could no longer afford the tuition fees, and needed Guy to help support the family by working in the fields.

Life in Mara changed forever in the summer of 2003 when 200 members of the government-backed Janjaweed — Arabic for “devils on horseback” — attacked the agrarian village of 2,000. The Janjaweed,rebranded as the Rapid Support Forces in 2013, were notorious for their indiscriminate violence, and were condemned by Human Rights Watch in 2004 for inflicting “a campaign of forcible displacement, murder, pillage, and rape on hundreds of thousands of civilians.” While no longer commanding headlines, Darfur continues to be the scene of horrific ethnic violence orchestrated by the regime in Khartoum and Arab militias like the Janjaweed.

As members of Darfur’s predominant non-Arab Fur tribe, considered ethnically inferior by the ruling National Congress Party and the Janjaweed, Guy and his family were targeted and savagely beaten.

“We were drinking tea,” Guy said. “My younger brothers were playing with our goats and scattering seeds to the doves in the yard when I suddenly heard gunshots. Several men appeared on horseback and began burning my family’s home.”

The men brandished Kalashnikovs, and Guy instantly knew they were members of the Janjaweed. “There was no time to say anything to anyone in my family. I was only thinking about how to get out of there.”

The image of a Janjaweed militant standing over his unconscious father, clenching a sharp wooden stick, would be Guy’s final memory of his home.

Becoming Guy

Fleeing his village with a broken arm and bloodied leg, Guy had no plan. As dusk approached, his chances of surviving the treacherous terrain dwindled. “As I was walking, I saw a car approaching. It was a medium-sized van with blue and white labels on the side.” Officials from the United Nations, who were posted at a nearby village, found Guy, wounded and distressed, and took him with them to Khartoum.

Living with Joseph, a British U.N. official in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, Guy grew proficient in English and enrolled at the local Young Men’s Christian Association. It was Joseph’s altruism and the intimate rapport he developed with a local pastor named Guy, that prompted Abdelhamid Yousif Ismail to convert from Islam to Christianity and change his name. (Neither Joseph nor the pastor’s last names were disclosed as a protective measure.)

“I had seen what people in Sudan had done in the name of Islam,” Guy said. “Killing is a crime and is never justified by the Quran. I no longer trusted the Islamic religion and felt that I could no longer be a part of it.”

“I kept on running”

But Khartoum was far from a permanent safe haven, since apostasy there is a crime punishable by death. His close contact with U.N. official Joseph had fueled rumors that Guy was leaking information about the Janjaweed’s atrocities in Darfur to the wider international community.

Arrested and brutally tortured on three on occasions by National Congress Party (NCP) operatives, Guy was given a week to flee Sudan or be killed. During one detention, Guy said “they kicked me in the head,” leaving a protruding dent at the far-left corner of his forehead, and “stomped on me and spat on me. One interrogator used my body as an ashtray and burnt me on my arm with his cigarette. I spent a couple of hours standing alone in a cell. There were metal spikes coming out of the walls of the cell that prevented me from moving. I saw other prisoners who were hanging by their arms above their heads being pulled by rope.”

Escaping Sudan via Egypt and then Israel is a common but perilous route. This February, Israel’s Population and Immigration Authority reported that more than 15,400 people had fled from Sudan and sought asylum in the Jewish state between 2009 and 2017.

Guy’s dream refuge in Israel stemmed from his belief that the Jewish people and Darfuris had both been victims of intolerance, conflict, and violence. “I knew nothing about Judaism or Israel until I started learning from the people at the U.N.,” he said. “Israel’s origin story with the Holocaust and all the Jewish people’s suffering resonated with me deeply after seeing my people’s suffering in Darfur.”

Of the 23 men with whom Guy escaped Sudan, on the eve of the first night of Ramadan, only 10 made it across the border unscathed. The rest were either shot by Egyptian border police or caught and tortured by Bedouin smugglers, who prey on Sudanese and Eritrean escapees for lucrative organ harvesting.

“I took off my shoes and tied them to my waist”, Guy said, eyes clinched. “I saw a hole in the fence that I assumed had been made by people trying to cross the border before me. I started running straight toward the hole in the fence. The guy in front of me hit a trip wire. Immediately we heard gunshots being fired at us from the right side. I kept on running.”

Finding freedom … and his brother

On the Israeli side of the border, Guy spent a month at a refugee camp in the Negev Desert before being granted a temporary license (an I.D. card used to identify Sudanese asylum seekers in Israel so they could gain employment). Guy then moved to Tel Aviv. It was there he chanced upon someone he thought had been massacred at the hands of the Janjaweed: his brother, Adam Yousif Adam.

“I was in shock when I saw my brother Adam again for the first time,” Guy said, grinning uncontrollably. “He had been shot while crossing the border from Egypt into Israel. I asked him about our family, but he said he did not know anything about them. We did not talk about the Janjaweed attack.”

After five years in Israel, studying at Levinsky College of Education, volunteering at the African Refugee Development Center (ARDC), and working as a dishwasher and cook at a popular Tel Aviv café, Guy set his sights on America. His dream of studying in the U.S. was realized when he was accepted to study political science and international law at the College of Lake County in Illinois, graduating May 2016.

Guy later applied to Harvard because he was drawn to the University’s legal studies program at the Extension School. He says he was also inspired by stories about Harvard’s diverse and multi-national student population and the respect extended to students such as Guy.

With a graduation goal of 2020, Guy continues to participate in humanitarian work supporting Darfuri refugees in Israel and the U.S., and he remains vocal about the humanitarian crimes perpetrated by the National Congress Party. He is currently the partnerships editor at The Africa Policy Journal, a Harvard Kennedy School student publication.

Guy says he dreams of harnessing his education to transform Darfur and the wider turbulent region. For him, the pursuit of education is a potent remedy to the Sudanese government’s brutalities and flagrant violations of human rights. “My people are not educated,” Guy said. “What I want to do is to help them go to school and study to try to protect our country. I believe that as human beings we are equal, whatever our color: black, white, pink, or blue.”

Jonathan Harounoff is a British graduate of the University of Cambridge where he studied Arabic, Persian, and Middle Eastern studies. At Harvard University, Harounoff studied negotiation, diplomacy, and journalism from August 2017 to May 2018; he was also a graduate teaching fellow at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health this past spring. Harounoff will be pursuing a master’s degree in journalism at Columbia University this fall.