Mortality in Darfur Revisited: What We Must Face

Eric Reeves | August 17, 2018 | https://wp.me/p45rOG-2hh

How many have died—directly and indirectly—from the past fifteen years of genocidal violence in Darfur? The last UN estimate was over a decade ago—April 2008—300,000. This figure is still virtually the only one cited in news reports on Darfur, but this is clearly a vast understatement, given the violence, displacement, and appalling conditions in many of the camps for displaced persons that have persisted in the intervening ten years.

The number of deaths directly caused by continuing violence targeting non-Arab/African populations and communities was long ago overtaken by the number dying indirectly from the effects of violence, the consequence of: lack of food and water following the flight from destroyed villages; poor medical and sanitary conditions in the displaced persons camps to which they fled; deferred mortality from acute malnutrition, as food sources were violently destroyed in vast quantities; suicide (particularly among women who have been victims of rape); deaths from Unexploded Ordnance (UXO); and many other causes that can be traced to original acts of violence.

In August 2010, following a series of efforts to supplement the UN figure of 300,000 with additional data and reports, I offered a lengthy survey and analysis of all extant data and reports on mortality, spurred in part by a rich analysis containing critical data gathered in eastern Chad in a report entitled “Darfurian Voices,” July 14, 2010) | http://www.darfurianvoices.org/ (researchers included Jonathan Loeb, primary researcher and author for the last three major human rights reports on Darfur from human rights groups Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch):

QUANTIFYING GENOCIDE: Darfur Mortality Update, 6 August 2010 (http://sudanreeves.org/2017/01/05/quantifying-genocide-darfur-mortality-update-august-6-2010/)

I attempted a limited update in November 2016 following use by The Guardian (UK), July 7, 2016 of my 2010 estimate of 500,000 dead from all causes in Darfur and eastern Chad.

My figure following the 2016 update was approximately 600,000, with acknowledgement that it could only be an extrapolation from data and reports previously published. Given the heterogeneity of the data, there could be no precise way to establish a margin of error. The figure may be significantly lower or higher. But I believe we may be morally certain that fifteen years of genocidal destruction in Darfur and eastern Chad have claimed the lives of more than half a million Darfuris, overwhelmingly of non-Arab/African ethnicity. To be sure, violence within and between Arab tribal groups has produced significant mortality, but nothing that is comparable to the death toll from Khartoum’s assault on the civilian populations perceived as supporting Darfur’s rebel groups in its genocidal “counter-insurgency on the cheap.”

The author of this phrase argued powerfully in August 2004 that there is something different about the Darfur genocide—different from previous genocidal campaigns by the Khartoum regime:

But this is not the genocidal campaign of a government at the height of its ideological hubris, as the 1992 jihad against the Nuba was, or coldly determined to secure natural resources, as when it sought to clear the oilfields of southern Sudan of their troublesome inhabitants. This is the routine cruelty of a security cabal, its humanity withered by years in power: it is genocide by force of habit.

Perhaps it is their very experience in previous genocides that has taught Khartoum’s génocidaires how to be particularly, ruthlessly efficient in human destruction—and how to destroy human lives with minimal costs, although clearly the costs of fifteen years of conflict have far exceeded what the Khartoum regime expected—certainly by regime president Omar al-Bashir, who in 2010 was served an arrest warrant by the International Criminal Court charging him with multiple counts of genocide in Darfur (this following an arrest warrant in 2009 charging al-Bashir with massive “crimes against humanity” in Darfur).

Khartoum has drawn various “red lines” on what may be reported from Darfur by humanitarian organizations, and morality—along with rape—is one of them, as I was informed by a senior UN official responsible for mortality data in 2006. He indicated to me that the threats made by the regime against those who had collected mortality data to that point were of a sort to preclude any further UN efforts. This is why in April 2008 the estimate offered by Sir John Holmes, head of UN humanitarian operations, was simply a crude extrapolation from the UN figure of 2006 (200,000).

Mortality estimates in the impossibly difficult reporting climate of Darfur are inevitably prone to error, although the UN figure of 200,000 in 2006 was established with considerable rigor, and Holmes’ 2008 extrapolation was reasonable, if conservative. But we must choose between making the most representative statistical estimate possible, or—as news organizations have chosen to do—continue with a now preposterous 2008 UN figure of 300,000.

For it is now 2018, and the violence continues, particularly in Jebel Marra over the past four fighting seasons. The establishment of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in 2013 as Khartoum’s primary military proxy in Darfur—indeed, the RSF is now officially part of the regime, and exceedingly well paid and armed—ensured that destruction on a vast scale would continue. For the single year of November 2014 – November 2015, see:

“Changing the Demography”: Violent Expropriation and Destruction of Farmlands in Darfur, November 2014 – November 2015″ | http://sudanreeves.org/2017/10/15/changing-the-demography-violent-expropriation-and-destruction-of-farmlands-in-darfur-november-2014-november-2015/

The scale of destruction—represented in an extensive data spreadsheet and mapped onto three separate maps of Darfur—makes clear how substantial violence was, particularly in East Jebel Marra (a broad area to the east of the Jebel Marra massif that includes areas of North Darfur, South Darfur, and Central Darfur). And even now, both Jebel Marra and East Jebel Marra, as well as many areas in South Darfur and elsewhere, are experiencing levels of violence that produce—directly and indirectly—high human mortality.

This reiteration of my conclusions about mortality in the Darfur genocide was prompted by a short dispatch today in Radio Dabanga:

Pregnant woman haemorrhages to death in North Darfur hospital | Radio Dabanga, August 16, 2018 | KUTUM

On Tuesday, a pregnant woman reportedly died at Kutum Hospital in North Darfur after bleeding for more than 12 hours, as there was no doctor at the hospital to attend to her. Residents from Kutum told Radio Dabanga that the hospital has only one doctor and a number of nurses, where the doctor works for limited hours. They complained of deterioration of environmental conditions, treatment services and lack of doctors and specialists in the hospital.

Should we think of this death as indirectly caused by the violence that has long been explosively evident and uncontrolled in the Kutum area of North Darfur as well as nearby Kassab camp? For humanitarians, it is one of the most dangerous and inaccessible areas in all of Darfur. Would there have been adequate medical staff at the hospital, beyond the one overworked doctor, if humanitarian organizations on the ground in Darfur had been given security and access by the Khartoum regime? I think the likely answer is “yes.” But like so much about mortality in Darfur, we can’t be sure. We do, however, know a great deal about the regime’s unrelenting hostility to international humanitarian organizations, as well as its continuing obstructionism and denial of access to areas desperate for humanitarian relief.

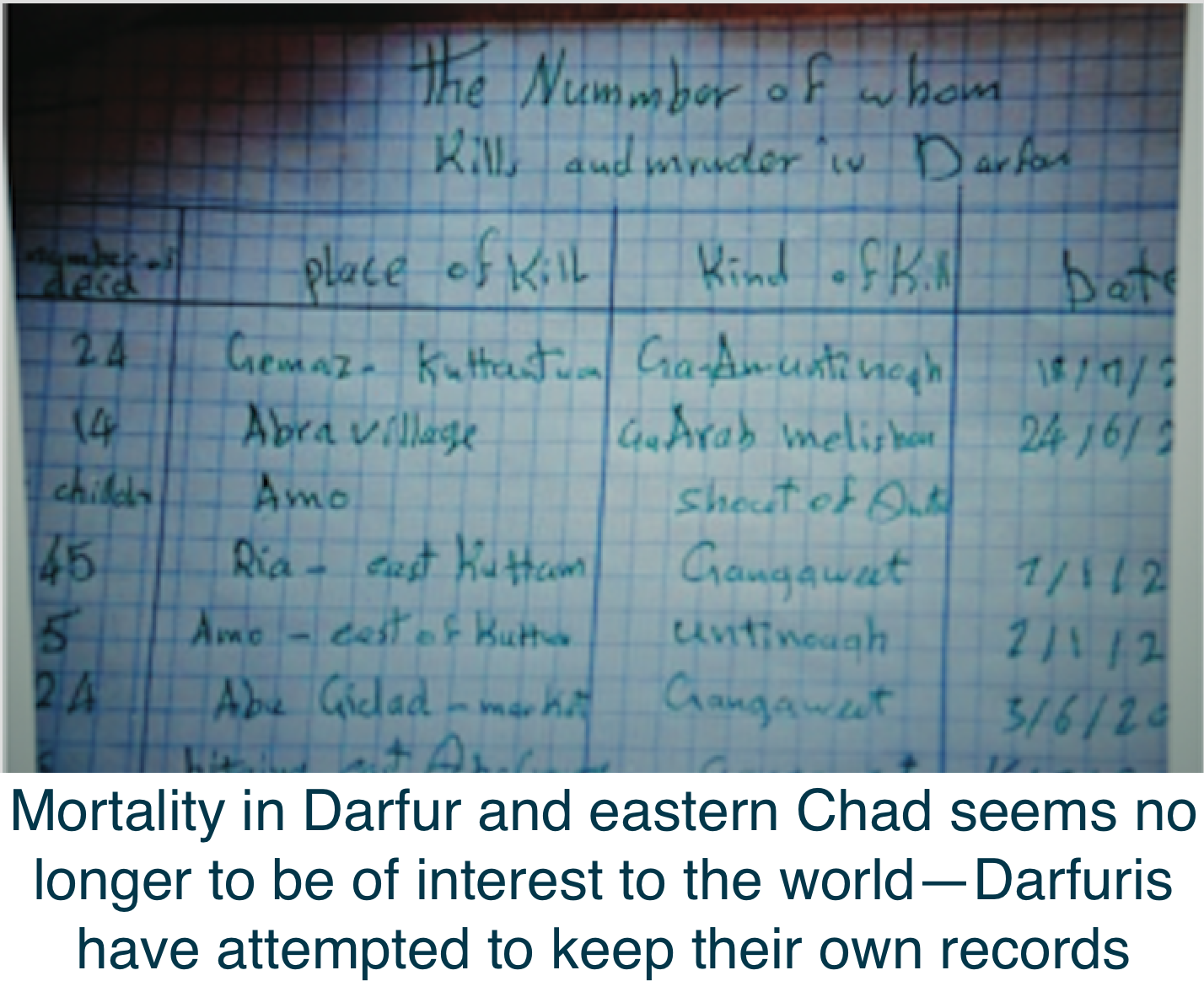

But a lack of certainty cannot make best possible mortality calculations irrelevant to understanding the history of the Darfur genocide. We can be certain that the 2008 UN figure of 300,000 is far too low, and the effects of its being continually re-cycled over a decade later are unacceptable, finally immoral—immoral because to make no effort to count the number who have died from what has been a clearly genocidal counter-insurgency by the Khartoum regime emboldens that regime to continue with its ghastly, violent militia predations and plans to force displaced persons to return to villages and land that either do not exist or have been occupied by armed Arab groups and militia elements. The figure of 300,000 amounts to a terrible moral discounting of the lost lives that have simply not been seen as worth counting.

If I am correct in my estimation, the mortality from the Darfur genocide now falls within the range of estimates offered for the Rwanda genocide of 1994 (500,000 – 1,000,000, with 800,000 the figure most often cited).

The ignominious withdrawal of the failing UN/African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) is possible in large measure because a reasonable account of the scale of violence, and the mortality directly and indirectly caused by that violence, is not part of the international discussion of what should be done in Darfur. And what we may be certain of is that the withdrawal of UNAMID, the growing Western rapprochement with the genocidal Khartoum regime, and the lack of any meaningful plan for the roughly 3 million displaced persons of the region will produced a great deal more mortality…a very great deal.

Appendix:

I have been much influenced in my thinking about mortality in Darfur by the work of Francesco Checchi, Professor of Epidemiology and International Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, particularly his “Interpreting and using mortality data in humanitarian emergencies: A primer for non-epidemiologists,” Humanitarian Practice Network, September 2005, No. 52, Francesco Checchi and Les Roberts (38 pages). I take as indisputable his opening remark:

The starting premise of this paper is that the primary, most immediate goal of humanitarian relief is to prevent excess morbidity and mortality. Similarly, any excess mortality should lead to a reaction. In this respect, mortality is the prime indicator by which to assess the impact of a crisis, the magnitude of needs and the adequacy of the humanitarian response.

I am very grateful for Professor Checchi’s comment on my mortality work, given to a journalist for the Christian Science Monitor:

“Reeves has an activist agenda but ‘he knows Darfur well.’ What he’s done is mathematically correct’ and ‘sufficiently legitimate’ to establish a high-end count.” (August 31, 2006)

Over the past twelve years I have continued to use the same methods and knowledge of Darfur in calculating mortality.