Just How Effective a “Watchdog” is the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons? Sudan as a test case…

Eric Reeves | March 29, 2018 | https://wp.me/p45rOG-2ei

In the wake of the recent Russian attempt to murder two former Russian nationals in Britain, the New York Times rightly recalled an event that occurred in the Kremlin last fall:

“Russia, Praised for Scrapping Chemical Weapons, Now Under Watchdog’s Gaze” | New York Times, March 20, 2018 (London)

Last fall [2017], President Vladimir V. Putin summoned a Kremlin television crew to his residence for a ceremony marking the destruction of Russia’s last declared stocks of chemical weapons.

The occasion called for a touch of theater: Shells were dismantled on camera, decorated with flowery Cyrillic script reading, “Farewell, chemical weapons!” Mr. Putin spoke proudly of Russia’s status as a peacemaker, and derided the United States for lagging behind. An official from the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), the global body that monitors agreements to whittle down stockpiles, stood by, beaming…

There is no reason to believe that the activities of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), monitoring or otherwise, had anything to do with Putin’s supposed decision to bid “farewell” to chemical weapons. Moreover, it is now clear that the event was a complete charade and that Russia maintains a stockpile of chemical weapons of unknown scale.

But with the OPCW in the spotlight, if indirectly, it is worth looking at how corrupt an organization it has become, certainly with respect to its treatment of Sudan and the Khartoum regime, which for more than 20 years has used chemical weapons against civilians in ways that clearly violate the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), which came into force in 1997 (the full name of the agreement is the “Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction,” and is based in The Hague). The mandate of the OPCW is to monitor and secure compliance with the CWC.

In other words, there is and has long been what should have been unignorable evidence of chemical weapons use by the National Islamic Front/National Congress Party regime in Khartoum, extending back to the very beginning of the CWC.

The earliest report containing such definitive evidence comes from Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (Switzerland): “Living under aerial bombardments: Report of an investigation in the Province of Equatoria, Southern Sudan,” February 20, 2000. It seems appropriate in the present context to cite at length from this report, as I incorporated it into my 2011 monograph on the Khartoum regime’s extraordinarily widespread and sustained bombing of civilians and humanitarians in greater Sudan:

[ “They Bombed Everything that Moved”: Aerial military attacks on civilians and humanitarians in Sudan, 1999 – 2011 (original publication: May 2011; updated 2011, 2012, September 2013); extensive data spreadsheet included | https://wp.me/p45rOG-1lh ]

My citations from the MSF report included the following (all emphases have been added unless otherwise noted):

Since the beginning of the year 1999 until this very moment, we have been experiencing and witnessing direct aerial bombings of the hospital, while full of patients, and of the living compound of our medical team (10 bombings in 1999, a total of 66 bombs dropped, with 13 hitting the hospital premises) [emphasis in original]. Facing the sharp increase of aerial bombardments in this region during 1999, frequently aimed at civilian structures such as hospitals, in November 1999, we requested an investigation of these events and their consequences for the civilian population in the area.

The elements of this investigation, included in the report herewith, tend to demonstrate that the strategy used by the Sudanese Air Force in this region, is deliberately aimed at targeting civilian structures, causing indiscriminate deaths and injuries, and contributes to a climate of terror among the civilian population. Furthermore, evidence has been found and serious allegations have been made that weapons of internationally prohibited nature are regularly employed against the civilian population such as cluster bombs and bombs with “chemical contents.”

As I pointed out at the time (2011), the use of chemical weapons by Khartoum has never been properly investigated by the UN or the OPCW; nor has the international community pushed effectively for such investigation. Despite very strong prima facie evidence that the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) had engaged in chemical warfare on a number of occasions, a decade after the end of the Iraqi Anfal, the international community—and the OPCW in particular—showed no interest in investigating:

MSF is particularly worried about the use or alleged use of prohibited weapons (such as cluster bombs and chemical bombs) that have indiscriminate effect. The allegations regarding the use of chemical bombs started on 23 July 1999, when the villages of Lainya and Loka (Yei County) were bombed with chemical products, was of particular note. In a reaction to this event, a group of non-governmental organizations had taken samples on the 30th of July, and on the 7th of August; the United Nations did the same.

Although the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) is competent and empowered to carry out such an “investigation of alleged use,” it needs an official request made by another State Party. To date, we deplore that OPCW has not received any official request from any State Party to investigate, and that since the UN samples taking, no public statement has been made concerning these samples nor the results of the laboratory tests.

MSF offers several eyewitness accounts of chemical weapons in bombs, including a grim narrative of events in Yei County (now Central Equatoria):

The increase of the bombings on the civilian population and civilian targets in 1999 was accompanied by the use of cluster bombs and weapons containing chemical products. On 23 July 1999, the towns of Lainya and Loka (Yei County) were bombed with chemical products. At the time of this bombing, the usual subsequent results (i.e. shrapnel, destruction to the immediate environment, impact, etc.) did not take place. [Rather], the aftermath of this bombing resulted in a nauseating, thick cloud of smoke, and later symptoms such as children and adults vomiting blood and pregnant women having miscarriages were reported.

MSF continued:

These symptoms of the victims leave no doubt as to the nature of the weapons used. Two field staff of the World Food Program (WFP) who went back to Lainya, three days after the bombing, had to be evacuated on the 27th of July. They were suffering of nausea, vomiting, eye and skin burns, loss of balance and headaches.

After this incident, the WFP interrupted its operations in the area, and most of the humanitarian organizations that are members of the Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) had to suspend their activities after the UN had declared the area to be dangerous for its personnel.

Subsequent Chemical Weapons Use by the Khartoum Regime

There have been repeated reports of chemical weapons use by the Khartoum regime after 1999; not one has been investigated by the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Indeed, during the 2016 assault by Khartoum’s forces on the Jebel Marra region of Central Darfur, Amnesty International provided overwhelming evidence of the use of chemical weapons against civilians nowhere near military fighting.

Much of the report—“Scorched Earth, Poisoned Air: Sudanese Government Forces Ravage Jebel Marra, Darfur,”Amnesty International | 109 pages; released September 29, 2016—was given over to the use of chemical weapons in Khartoum’s military offensive, directed primarily against civilians. Given the massive body of evidence assembled, there can be no reasonable doubting the use of chemical weapons—certainly not in light of the professional analysis (by experts in non-conventional weapons) and the scores of photographs that reveal destruction of human flesh, internal organs, and illnesses that cannot be accounted for my any known human pathogen or conventional military weapon.

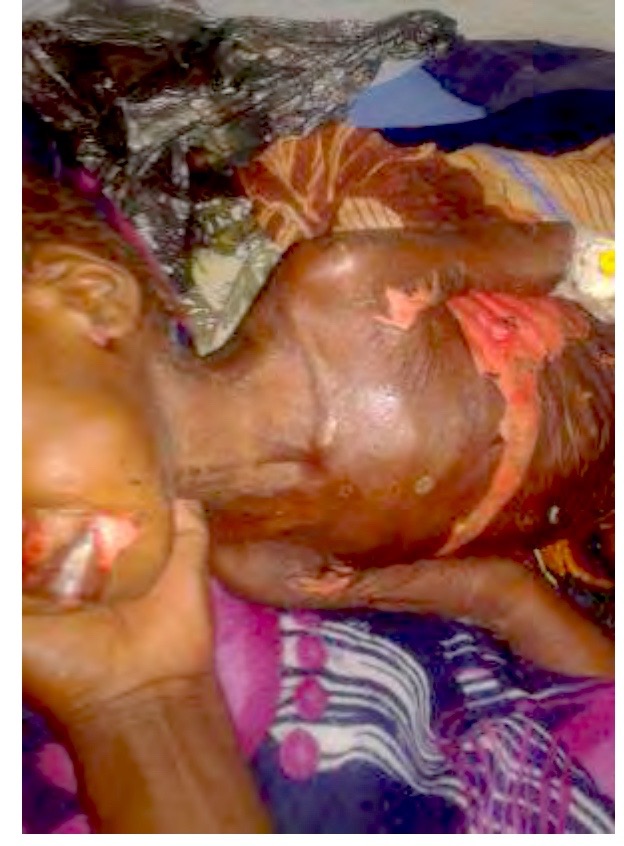

An infant dying from a chemical weapons attack during the 2016 Jebel Marra campaign by the Khartoum regime

We lack physical evidence in the sense that we don’t have soil or bomb fragments samples, or blood samples. But there is simply no other reasonable explanation for what is revealed in these gruesome photographs, or in the remarkably consistent accounts that came from widely separated areas of the Jebel Marra massif. Khartoum, of course, has allowed no independent investigators into Jebel Marra and the international community has not pushed for such. But again, the photographs of individual who were victims of attacks make clear than no known pathogen or conventional military weapon could possibly account for the nature or similarities of injuries visible after the attacks.

This pattern of injury is common among those who were exposed during chemical weapons assaults

The weapons used by Khartoum clearly violated the Chemical Weapons Convention (see Article 10); for its part the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons has a clear mandate to investigate credible allegations of chemical weapons use. Indeed, the OPCW “Mission Statement” could hardly be clearer:

The mission of the OPCW is to implement the provisions of the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) in order to achieve the OPCW’s vision of a world that is free of chemical weapons and of the threat of their use, and in which cooperation in chemistry for peaceful purposes for all is fostered. In doing this, our ultimate aim is to contribute to international security and stability, to general and complete disarmament, and to global economic development.

To this end, the Secretariat proposes policies for the implementation of the CWC to the Member States of the OPCW, and develops and delivers programmes with and for them. These programmes have four broad aims:

…to ensure a credible and transparent regime for verifying the destruction of chemical weapons and to prevent their re-emergence, while protecting legitimate national security and proprietary interests;

This terrible peeling away of skin is also common among many of the victims of the chemical weapons assaults in Jebel Marra

Member states of the OPCW represent approximately 98 percent of the world’s population, and Sudan is a signatory to both the CWC and the OPCW. The United States has an elaborate Web page given over the CWC (http://www.cwc.gov/).

But Western nations were content to dither, even as the obstacles to investigation grew greater. As Sudan Tribune reported (October 9, 2016), Khartoum’s génocidaires were quickly provided propaganda help from the hopelessly ineffective and morally corrupt UN/African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID):

Sudan’s Foreign Ministry has said that the head of the hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) Martin Uhomoibhi stressed that his mission didn’t receive any piece of information that chemical weapons have been used in Darfur…. In a press statement extended to Sudan Tribune on Sunday, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Gharib Allah Khidir said Uhomoibhi told [Foreign Minister Ibrahim] Ghandour that in spite of the almost 20,000 UNAMID personnel on the ground in Darfur, none of them has seen any Darfuri with the impact of the use of chemical weapons as described by Amnesty International’s report.

He added the UNAMID chief informed Ghandour that not one displaced person meeting such description has shown up at any UNAMID Team Site clinics where they would have naturally gone for help.

What UNAMID was content not to investigate for lack of access to Jebel Marra

Even leaving aside the habitual mendacity of Ibrahim Ghandour, it should be noted that Uhomoibhi proved quite as feckless, ineffective, and dishonest as the disingenuous and corrupt previous heads of UNAMID, most notably Rodolphe Adada and Ibrahim Gambari. He is all too likely to have said what Ghandour has attributed to him. But the fact remains that Uhomoibhi was simply untrustworthy and proved himself a tool of Khartoum on too many occasions—nowhere more than on this occasion.

It should be noted first that at the time of Uhomoibhi’s statement it had been years since UNAMID has had any real access to Jebel Marra, in particular to the areas where chemical weapons were reported by Amnesty. It was also quite telling that Uhomoibhi did not explain why his force of 20,000 personnel didn’t gather evidence disconfirming Amnesty’s findings. The reason was simple: the Mission could not gain access to the areas specified in Amnesty’s report.

Another dying infant that UNAMID managed not to see…

As a reporting source, no one seriously engaged in assessing realities in Darfur regards UNAMID accounts as anything but the disingenuous efforts of a failing Mission trying to do what it can to disguise that failure. To be sure, we can’t know whether UNAMID indeed failed so miserably as to have heard none of what Amnesty reports on the basis of more than 250 interviews that serve as the evidentiary backbone of its report, along with the searing photographs of chemically ravaged flesh—or whether there is lying or concealment of evidence at some level in whatever passes for a “reporting chain of command” in this deeply demoralized and impotent force. It is difficult to know which of these failings would be greater, given the history of UNAMID over the past ten years (as of March 2018).

For its part, the international community had a stark choice in the wake of the Amnesty International report:

[1] Believe UNAMID chief Uhomoibhi—and Ibrahim Ghandour, who represents a regime that has lied and abrogated treaty obligations on countless occasions, including continuously denying access in Darfur to UNAMID, despite having signed the Status of Forces Agreement of January 2008, which explicitly guarantees unfettered access—throughout Darfur—to the Mission;

[2] Accept that Khartoum will refuse to allow an investigation under the auspices of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, but still demand that such an investigation be conducted, thereby compelling Khartoum to violate again, and conspicuously, its obligations under the Chemical Weapons Convention.

The choice was made and the world sees in Russia’s recent chemical weapons use in the UK the one result of an OPCW that refuses to take its investigatory mandate seriously.

It should be said as well that the former head of the UN’s Department of Peacekeeping operations, Hervé Ladsous, had a dismal record on Darfur, but was cited by the UN News Center, several days after the release of the Amnesty report:

Regarding allegations that the Government had used chemical weapons in Jebel Marra, Mr. Ladsous said that the UN had not come across any evidence to support such claims. He pointed out, however, that UNAMID had consistently been denied access to conflict zones in Jebel Marra, and that the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) had stated, in an initial assessment, that it was not possible to draw any conclusions without further information and evidence being made available. (UN News Centre, October 4, 2016)

In fact, Ladsous seriously misrepresented here what OPCW had said to date; it did not include language supporting Ladsous’ claim that OPCW had declared “it was not possible to draw any conclusions without further information and evidence being made available.” Here, in its entirety, is all that OPCW has reported on its website

OPCW Examining NGO Report on Allegations of Chemical Weapons Use in Sudan | Thursday, 29 September 2016

In response to questions regarding the Amnesty International report, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) is aware that Amnesty International issued the report, “Scorched Earth, Poisoned Air: Sudanese Government Forces Ravage Jebel Marra, Darfur,” which includes some allegations of the use of chemical weapons in the Darfur region of Sudan. OPCW shall certainly examine the reports and all other available relevant information.

There is no evidence of a serious examination by OPCW.

But Ladsous’ disingenuous construal of the OPCW statement does little to encourage belief that the UN will take any meaningful part in at least forcefully demanding an investigation, even as such an investigation is the only way in which Amnesty’s conclusions could be confirmed or disconfirmed on the basis of physical forensic analysis. In the end, Khartoum’s view of things as represented at the UN by the regime’s representative, Omer Dahab Fadl Mohamed, will prevail by default:

Sudan’s UN Ambassador Omer Dahab Fadl Mohamed responded in a statement calling the Amnesty report “baseless and fabricated” and denying that his country had any chemical weapons. (Associated Press, October 1, 2016 | New York)

It was hardly headline news, but following release of the Amnesty report the Parliament of the European Union demanded an investigation of Khartoum’s chemical weapons use; but, conveniently for the countries nominally represented, the Parliament has negligible power or influence within the EU. At the time, France, Britain, the UK, and the U.S. were rumored as possible initiators of a petition for investigation by the OPCW, but this came to naught. The “moral obscenity” of chemical weapons use—as then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry would put it when it was expedient to say as much—proved but another obscenity in an unfathomably grim and destructive genocidal counter-insurgency, now fifteen years in duration.

A Final Appalling Note

With the help of the Africa bloc at the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article61915/), Khartoum was elected as Vice Chair of Executive Council of the OPCW. The Executive Council is responsible for the most important decisions by the Organization.

The extraordinary cynicism, finally cruelty of the Africa bloc at the Organization (Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Libya, Morocco, Senegal, South Africa, and Sudan) came just six months after Amnesty released its extraordinarily authoritative report on Khartoum’s massive assault on Jebel Marra.

The photographic evidence and innumerable interviews conducted by Amnesty left no room for doubt that the Chemical Weapons Convention was seriously violated by Khartoum, resulting in deaths and injuries to hundreds of civilians; many if not most of the victims were nowhere near rebel forces; an unconscionable number were children. The campaign in Jebel Marra had all the earmarks of a scorched-earth campaign of the sort that has frequently defined the regime’s genocidal counter-insurgency in Darfur over the past fifteen years.

The bizarre decision by the Africa bloc at the OPCW was sadly all too consistent with the many reports of Khartoum’s progress in rehabilitating itself within the international community, reports that began to accelerate with the lifting of sanctions on Khartoum by the Obama administration in its last week in office (January 2017). Even earlier many European nations—the UK in particular—had made clear that they were more than willing to engage in rapprochement with the Khartoum regime as a means of stemming African migration to the European continent.

Again, Britain was rumored to have considered bringing a request to the OPCW for an investigation of what was so definitively established as having occurred in Jebel Marra by Amnesty International. In light of recent events, perhaps the UK will now take the OPCW’s fulfillment of its mandate more seriously.