Genocide in Darfur: The Beginning and the Ending

Eric Reeves | February 25, 2018 | https://wp.me/p45rOG-2dR

Exactly fourteen years ago, the Washington Post published my survey of the evidence that Darfur was the site of genocide, as defined by the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (“Unnoticed Genocide”). Despite a few years of broad-based activism focusing on the Darfur genocide, the election of Barack Obama as President in 2008—and his subsequent appointment as Special Envoy for Sudan the wholly unqualified and buffoonish Scott Gration—fatally undermined the Darfur movement, on which Obama had unctuously campaigned as presidential candidate. Calling the “genocide” (his word) in Darfur a “stain on our souls,” Obama must accept that as part of his legacy, that stain has only grown deeper.

I have recently written about what now appears to be the “Final Phase of the Darfur Genocide” (http://sudanreeves.org/2018/02/17/the-final-phase-of-the-darfur-genocide-has-now-begun/). The final mortality total for the (now) slow-motion genocide cannot be calculated or even estimated, but there is good reason to think it will surpass the total for the 1994 Rwanda genocide (see | http://wp.me/p45rOG-AB/).

“Unnoticed Genocide,” The Washington Post

Eric Reeves, 25 February 2004

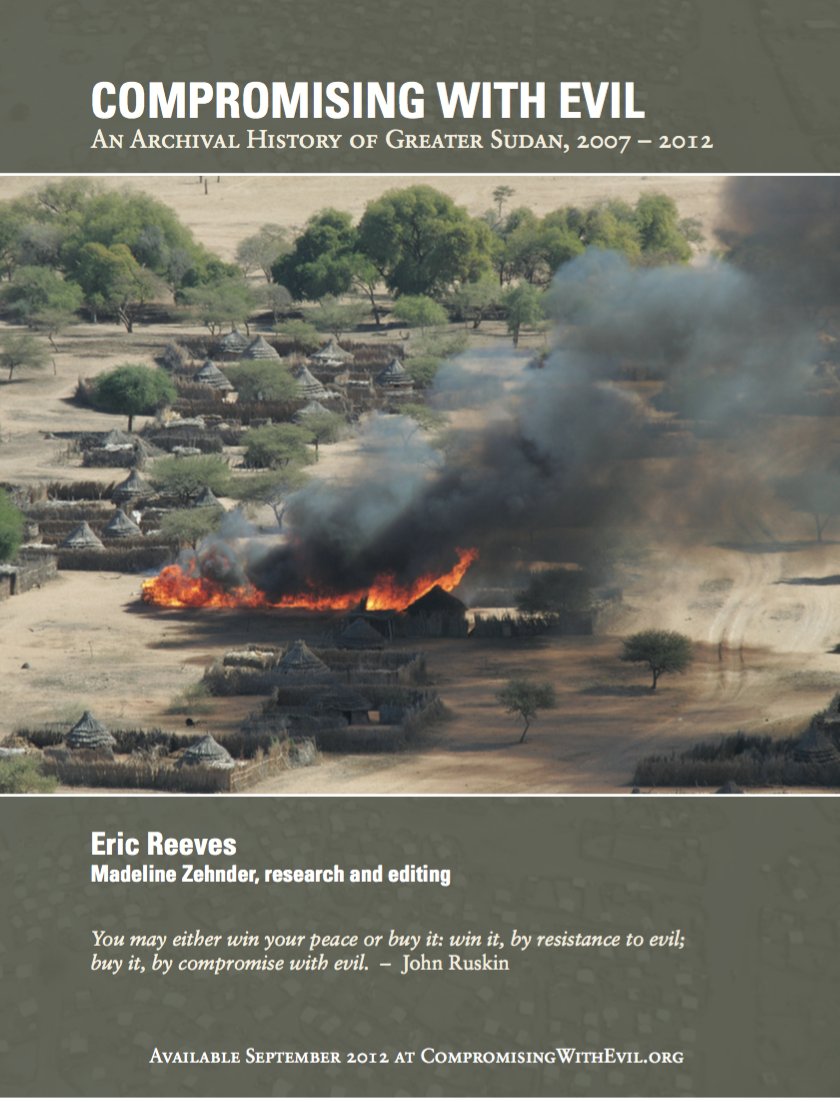

In the remote Darfur region of western Sudan, an unseen human disaster is rapidly accelerating amidst uncontrolled violence. The UN’s Undersecretary General for Humanitarian Affairs has declared that Darfur is probably “the world’s greatest humanitarian catastrophe.” Doctors Without Borders has recently observed “catastrophic mortality rates.” Amnesty International speaks of continuing “horrifying military attacks against civilians” throughout Darfur by the Sudan government and its militias. The government has sent bombers to attack undefended villages, refugee camps, and water wells. The UN estimates that 1 million people have been displaced by war and that more than 3 million people are now affected by armed conflict in the region.

Yet Darfur has remained virtually invisible, even though defined by these terrifying numbers and brutal realities. This is because the central government in Khartoum, the National Islamic Front, has allowed no news reporters into the region and has severely restricted humanitarian access, thus preventing observation by aid workers.

The war in Darfur is not directly related to Khartoum’s 20-year war against the people of southern Sudan. Even so, military pressure from the Darfur insurgency that began a year ago has been instrumental in forcing the regime to commit (nominally) to peace talks with the south. But there are now signs that these talks have been viewed expediently by Khartoum—as a means of buying time to crush the insurgency in Darfur, which emerged inevitably from many years of abuse and neglect.

Despite efforts by the regime, a slow and widening stream of information is reaching the international community, both from tens of thousands of refugees fleeing to Chad (which shares a long border with western Sudan), and from accounts coming precariously from within Darfur. Amnesty International has led the way in reporting on Darfur, and a recent release speaks authoritatively of countless savage attacks on civilians by Khartoum’s regular army, including its crude Antonov bombers, and especially by its Arab militia allies, called “Janjaweed.”

An especially disturbing feature of these attacks is the clear and intensifying racial animus. This has been reported by Amnesty International, the International Crisis Group, and various UN spokespersons. Indeed, the phrase “ethnic cleansing” has been used not only by the Humanitarian Coordinator for Sudan but the UN High Commission for Refugees. A number of wire services also report diplomats speaking of “ethnic cleansing.”

The phrase “ethnic cleansing” is an unfortunate, if convenient euphemism for genocide, one that gained currency under dubious linguistic and legal circumstances during the Balkan conflicts. But whether we speak euphemistically or bluntly, the terrible realities in Darfur require that we attend to the ways in which people are being destroyed because of who they are, racially and ethnically—“as such,” to cite the key phrase from the 1948 UN Convention on Genocide.

Darfur is home to a number of racially and ethnically distinct tribal groups. Although virtually all are Muslim, generalizations are hard to make. But the Fur, Zaghawa, Masseleit, and other peoples are accurately described as “African,” both in a racial sense and in terms of agricultural practice and use of non-Arabic languages. Darfur also has a large population of nomadic Arab tribal groups, and from these Khartoum has drawn its savage “warriors on horseback”—the Janjaweed—who are most responsible for attacks on villages and civilians.

The racial animus is clear from scores of chillingly similar interviews with refugees reaching Chad. A young African man who had lost many family members in an attack heard the gunmen say, ‘You blacks, we’re going to exterminate you.’ Speaking of these relentless attacks, an African tribal leader told the UN news service, “I believe this is an elimination of the black race.” A refugee reported these words as coming from his attackers: “You are opponents to the regime, we must crush you. As you are black, you are like slaves. Then the entire Darfur region will be in the hands of the Arabs.” An African tribal chief declared that, “The Arabs and the government forces…said they wanted to conquer the whole territory and that the Blacks did not have a right to remain in the region.”

There can be no reasonable skepticism about Khartoum’s use of these militias to “destroy, in whole or in part, ethnical or racial groups”—in short, to commit genocide.

Khartoum has so far refused to rein in its Arab militias; has refused to enter into meaningful peace talks with the insurgency groups; and most disturbingly, refuses to grant unfettered humanitarian access. The international community has been slow to react to Darfur’s catastrophe and has yet to move with sufficient urgency and commitment. A credible peace forum must rapidly be created. Immediate plans for humanitarian intervention should begin. The alternative is to allow tens of thousands of civilians to die in the weeks and months ahead in what will be continuing genocidal destruction.

Eric Reeves, a professor at Smith College, has written extensively on Sudan]