“Recalling Lincoln in the Wake of Charlottesville,” The Huffington Post, August 16, 2017

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/5994d062e4b00dd984e37c2c

By Eric Reeves

Most Americans are now struggling simply to make sense of the reality of a president who has conspicuously given encouragement to men and women who have in common an explicit racism and bigotry of the most extreme sort. The disparagement and hatred of African Americans and Jews has come to us in such brutal and unfiltered form in the wake of Charlottesville that our sense of outrage is overwhelmed, our ability to express fully our abhorrence is hobbled by the enormity of the hatred that has come into such sharp focus.

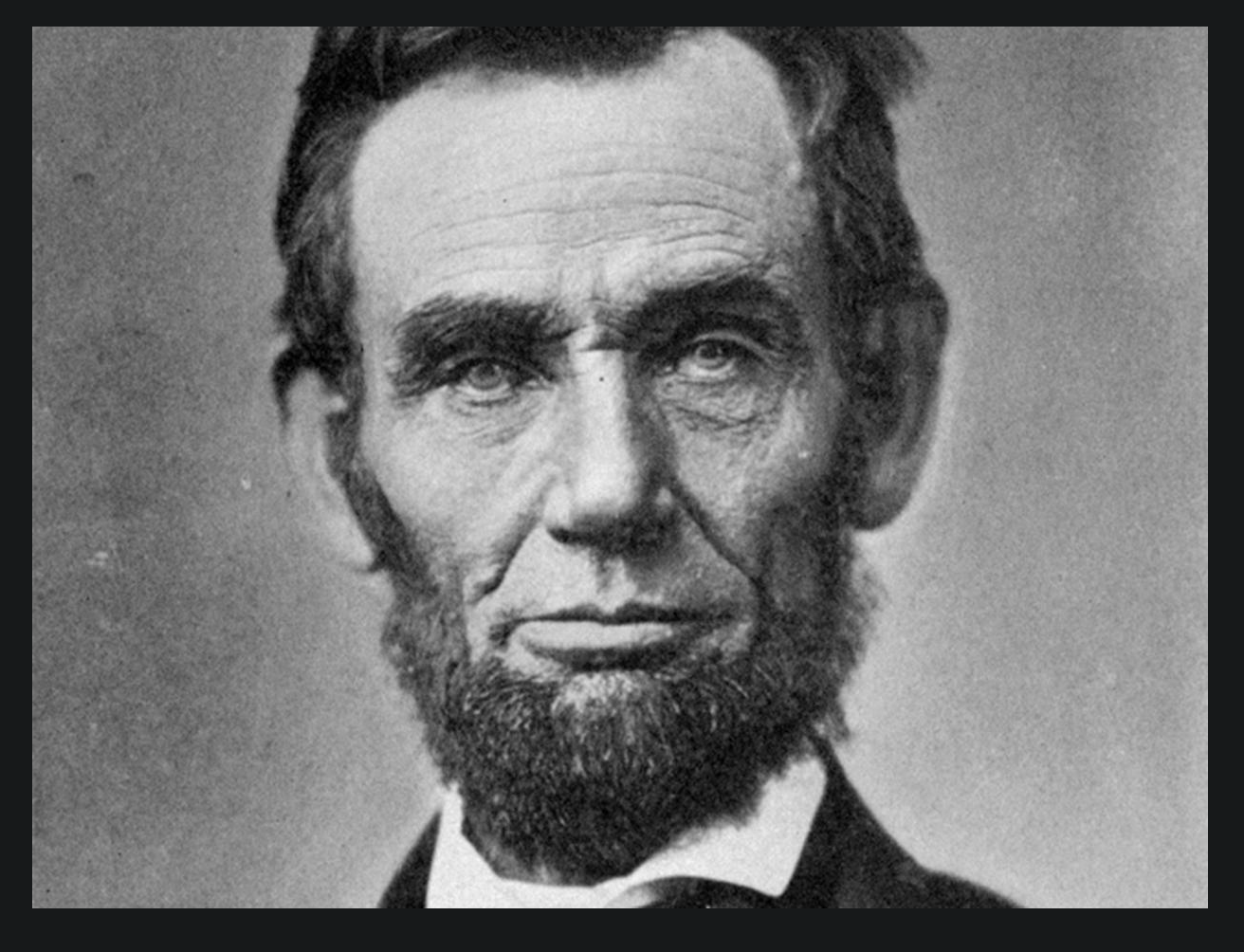

I offer no words of suitable outrage here, no expression of adequate abhorrence. But I would remind my fellow Americans lost in despair to recall a president who in his magnanimous and almost unimaginably courageous and tenacious determination to end slavery in our country demonstrated how great the American spirit can be when blessed with inspired leadership.

Abraham Lincoln is at once the archetypal American icon and a source of endless historical dispute. But I find no convincing argument that Lincoln was anything but ferociously committed to ending slavery in our country. Historians will debate endlessly the pragmatic and moral elements of his four years as president; but his Second Inaugural Address seems to me to have been precisely what Frederick Douglass described it as: a “sacred effort.” And it is worth our recalling that despite the omnipresence of contemptible and hateful words from our current president, his great predecessor still speaks more profoundly to us, perhaps even more so in our present grief and moral bewilderment.

In March 1865 the Civil War was largely over—and Lincoln himself would be assassinated in April of that year. These facts give to his Second Inaugural a valedictory quality that Lincoln himself could have only vaguely intuited. But for later audiences, Lincoln’s words sound enduring moral notes that make the thoughtlessness of white supremacy—and defenses of the Confederacy—painfully clear. Although both sides in the war “invoked [God’s] aid against the other,” Lincoln felt compelled to offer the most essential truth, even as he deliberately skirted broader judgments of his Southern foes: “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces…” Today, most Americans find a similar “strangeness” in the assertion of racial superiority—especially when that superiority is violently asserted, as it explicitly was by the Confederacy during the Civil War—and as it has continued to inform so many attitudes towards what the Confederacy represented.

We need look no further than these indisputable facts to understand the repugnance felt by so many at the erecting, decades later, of monuments celebrating this violent Confederate claim.

But it is Lincoln’s own assertion of perseverance that has, I believe, the deepest resonance for modern readers of this great document. At the time of the Second Inaugural some 600,000 men had lost their lives in the conflict; countless more were injured, and nearly all American families were in some way bereft or diminished by the war’s unimaginable violence. And yet Lincoln would insist,

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God will that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty hears of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousands years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

What should we in the 21st century hear in this archaic biblical invocation (Psalm 19) and the harsh commitment to military victory? I believe we should be reminded that there are some who have not accepted the full implications of the Union victory, and who are still willing to play the role of “bondsman.” In turn, we must accept that those so willing are to be confronted with the determination to expend all that is necessary of national blood and treasure to ensure that slavery, in all its forms, shall finally have been fully subdued in our country.

The greatest tragedy of the Trump presidency in the wake of Charlottesville is that we have seen the prospect of the revived “bondsman”; and we have heard the “bondsman” encouraged by equivocation and disingenuousness on the part of the chief executive of the United States.

Many find the biblical fervor of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural strange. But what cannot be strange to us is the lifelong, passionate moral response to human suffering that animates every word of this great American document. And should we need guidance in responding to the suffering that far too many would again inflict on the descendants of slaves, we would do well to recall how much Lincoln felt we as a nation must be prepared to sacrifice to end the moral catastrophe of failing truly to believe that “all men are created equal.”

[Eric Reeves is Professor Emeritus of English Language and Literature at Smith College]