On the Invisibility of Darfur: Causes and consequences over the past five years

Eric Reeves | October 22, 2016 | http://wp.me/p45rOG-1WS (Part Two at http://wp.me/p45rOG-1Xy)

The desperate, ongoing agony of Darfur continues without respite or diminishment. On the contrary, the past five years have seen an extraordinary acceleration of Khartoum’s genocidal counter-insurgency in the region, one that has been rendered invisible by the National Islamic Front/National Congress Party regime. Perhaps most consequentially, human rights groups are barred from the region, as are independent journalists from all news organizations, large and small. The reports from the UN/African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) are contemptible in their inadequacy and mendacity, and human rights reporting of necessity requires reports from the ground inside Darfur reaching outside sources, primarily Radio Dabanga and Sudan Tribune.

In turn, Western nations and other important international actors have begun to act on the view—only rarely articulated—that the Darfur crisis has somehow been “managed.” There is painfully little frank acknowledgement of what the Small Arms Survey (Geneva) found in a 2012 report (see below):

Since 2010 Darfur has all but vanished from the international agenda…

This ignorance of, or indifference to, the suffering and destruction of Darfuris is implicitly licensed by Khartoum’s success in turning Darfur into a “black box,” from which little information comes and is mainly disregarded, even when it comes from major human rights and humanitarian organizations.

The one exception to the “information blackout” is the extremely lengthy report of the UN Panel of Experts on Darfur (September 22, 2016). In this two-part overview I will make reference to the 194-page document in representing events of 2015, but for the present will note that it has received virtually no news coverage, even as the primary conclusion of the Executive Summary is unambiguous (it must be said at the same time that the copiousness of the document hasn’t translated fully enough into an account of humanitarian and human rights conditions):

The Panel conducted investigations into targeted attacks against the civilian population and civilian objects, the indiscriminate bombardment of civilian areas and sexual violence committed during the conflict. Responsibility for the violations is attributed to the Government. (S/2016/805)

Covering the period May through November 2015, the report of the Panel of Experts was delivered on December 4, 2015 to the UN Security Council (specifically, the “Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1591 (2005) concerning the Sudan”). But nefarious political machinations at the Security Council—primarily by Russia—all too predictably delayed public dissemination of the report. One consequence of the long delay in public release, well understood by Russia, is that the report no longer seemed “news,” even as it provides the only account directly from the ground concerning the situation in Darfur during this window in time. Only one news organization bothered to note the release of the report, and did so with remarkable brevity (Associated Press | September 28, 2016).

The news organization that had the greatest obligation to report on the findings of the UN Panel of Experts report was The New York Times, the news organization with the last dateline from Darfur outside one the three major cities of the region (Nyala, el-Fasher, and el-Geneina). The obligation rested heavily on the Times because of its extraordinarily distorted reporting on Darfur, reporting that convinced many that the catastrophe in Darfur had ended. From the village of Nyuru (near Mornei [also Murnei], a significant town in West Darfur), the Times reported on February 26, 2012 that peace was descending on Darfur. A prominent photograph accompanying the dispatch by Jeffrey Gettleman (the Times’ East Africa correspondent) carried an astonishing caption:

“…peace has settled on the region…”

But the conclusion drawn by the caption to this photograph was not simply wrong, it was grotesquely wrong. The Times’ correspondent had been taken to a “Potemkin Village,” certainly thronging with security officials and their informants. The same was true when UNAMID attempted to investigate the mass rapes of women and girls at Tabit, North Darfur, in November 2014. A subsequent investigation by Human Rights Watch established, on the basis of more than 50 interviews with residents or former residents of Tabit, not only that more than 220 girls and women had been raped by regular Sudan Armed Forces soldiers—on the orders of the nearby garrison commander—but that UNAMID investigators, when they were finally allowed into Tabit, found only terrified people unwilling to say anything about the onslaught of sexual violence.

In the case of Nyuru in West Darfur, we catch a glimpse of the realities that escaped the Times’ correspondent if we understand the implications of a recent dispatch from Radio Dabanga, with a very wide network of sources on the ground throughout Darfur. The dispatch concerns the displaced persons camps at Sese (also transliterated Sisi), some five miles from Nyuru, which served as the dateline for the Times dispatch:

People in a West Darfur camp for displaced people have moved away from the area as militiamen repeatedly attacked them on their farms, during a siege that lasted almost a week. State authorities have written an accord to maintain peace. Several times this month, residents of Sese camp in Kereinik locality who went out to farm were beaten by members of a paramilitary force and militant herders. A displaced man was shot dead. Now the Governor of West Darfur and the Sultan of the Masalit tribe, Saad Bahruldin, have intervened to convince the displaced people not to move away. (Radio Dabanga, October 21, 2016 [for a precise cartographic reference for both Nyuru and Sese/Sisi displaced persons camp, see the UN Field Atlas for West Darfur])

The Times dispatch begins very differently, declaring:

More than 100,000 people in Darfur have left the sprawling camps where they had taken refuge for nearly a decade and headed home to their villages over the past year, the biggest return of displaced people since the war began in 2003 and a sign that one of the world’s most infamous conflicts may have decisively cooled.

This was a conspicuously absurd assertion, justified only by the dubious claims of a deeply self-interested and self-protective UNAMID mission. It was decisively refuted by Jean Bosco, the UN representative of the UN High Commission for Refugees in Chad, speaking of the large Darfuri refugee population in eastern Chad. In an interview with Radio Dabanga following the Times’ dispatch, the UNHCR representative declared (Radio Dabanga, April 2, 2012):

So there are no people retained voluntary from Chad to Sudan officially under the coordination of UNHCR?

“No, what we call spontaneous repatriation is not organised by the UNHCR. People can decide to go by themselves. In such a case, the UNHCR doesn’t provide for any assistance. We heard that some Sudanese had repatriated. We asked our colleagues from UNHCR, even implementing personnel in the Darfur region. But none had been able to provide evidence that those people were living in the refugee camps in Chad. So right now I’m not in the position to certify that any refugee had repatriated from the refugee camps in Chad.”

I ask this question because we read in the international media that there is repatriation from Sudanese refugee camps in Chad from Sudan.

“No, this did not happen.”

In the last year, 2012, did there happen any repatriation?

“No, last year, nobody repatriated from the refugee camps.”

The farsha (chief administrative official) for Murnei traveled to Nyuru in the wake of the Times’ dispatch and could only express bewilderment at the Times’ claims about “returns.” No humanitarian organization or UN agency in Darfur report returns on anything approaching the scale reported by the Times.

The only remotely credible source cited by the Times was François Reybet-Degat, then head of the United Nations refugee office in Sudan. But almost as if to advertise his ignorance, Reybet-Degat offered a spectacularly tendentious and demonstrably inaccurate picture of security in Darfur: “There are still pockets of insecurity [in Darfur], but the general picture is that things are improving.” This assessment runs directly counter to every non-UN report on the situation in Darfur, before and after February 2012—something the Times should certainly have noted at some point.

“…but the general [security] picture [in Darfur] is that things are improving.” — François Reybet-Degat, in 2012 head of the United Nations refugee office in Sudan

Indeed, almost exactly contemporaneous with the Times’ dispatch was a report from Amnesty International (“No End to Violence in Darfur: Arms Supplies Continue Despite Ongoing Human Rights Violations” | February 2012). Among other key findings, Amnesty notes in its Introduction that:

The supply of various types of weapons, munitions and related equipment to [the government of] Sudan in recent years, by the governments of Belarus, the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation, have allowed the Sudanese authorities to use their army, paramilitary forces, and government-backed militias to carry out grave violations of international human rights and humanitarian law in Sudan. This ongoing flow of new arms to Darfur has sustained a brutal nine-year conflict which shows little sign of resolution.

In the last twelve months, as other developments in Sudan overshadowed international attention on Darfur, the region has seen a new wave of fighting between armed opposition groups and government forces, including government-backed militias.

Why was this important human rights study not cited by the New York Times—“All the news that’s fit to print”?

The Times’ dispatch is hopelessly at odds with all data on displacement, despite its celebration of an inexplicable “100,000” newly returned civilians. An analysis of UN and humanitarian figures for new displacement makes utter nonsense of the optimism suggested by the figure. Scandalously, the dispatch never makes fully clear whether this population reflects returns by IDPs or refugees in eastern Chad; but neither population experienced anything like the scale of return the Times suggests. Rather, human displacement over the past five years has been massive, significantly exceeding 1.4 million civilians. And in the five years prior to the Times’ dispatch, in a grim symmetry, more than 1.4 million people had also been newly displaced (see “Taking Human Displacement in Darfur Seriously” | June 3, 2013). In 2016, basing a figure on the estimate from the Amnesty International report on the Jebel Marra offensive (September 29, 2016), well over 250,000 people will have been newly displaced persons by the end of this year. Most of Jebel Marra is in the former West Darfur (now “Central Darfur”):

2012: 150,000 civilians newly displaced

2013: 400,000 civilians newly displaced as of June 1, 2013, according to UN figures

2014: 457,000 civilians were newly displaced, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM)

2015 250,000 civilians were newly displaced, according to UN OCHA

2016 250,000 (figure based on estimate by Amnesty International; see above)

In other words, approximately 1.5 million people have been newly displaced since publication of the Times’ dispatch—overwhelming by violence or fear of violence, and overwhelmingly civilians from the non-Arab/African tribal populations of Darfur. All the data for the period preceding February 2012 were of course available, though none were cited, with one imprecise and haphazard exception.

The number of Darfuris displaced within Darfur and as refugees in eastern Chad now exceeds 3 million people—overwhelmingly from the non-Arab/African tribal populations of Darfur. Some 500,000 people have died as a direct or indirect result of the conflict. Together, the two figures represent half the pre-war population of Darfur.

The gross journalistic malfeasance of the Times is in large measure responsible for the Khartoum regime’s decision not to grant further access to journalists. Not willing to push their luck, and having precisely the dispatch they wanted from the Times, there is no incentive to allow journalists—or even UNAMID or other UN or African Union officials—meaningful access to those locations in Darfur that are the scenes of the greatest violence and displacement. It is hardly surprising that despite the mass of compelling evidence of chemical weapons use in Jebel Marra compiled by Amnesty International, the head of UNAMID has declared that his force has seen no evidence of chemical weapons use whatsoever.

UNAMID chief Martin Uhomoibhi, with Khartoum’s Foreign Minister Ibrahim Ghandour; Uhomoibhi has said his force has seen no evidence of chemical weapons use in Jebel Marra

On the basis of a wide range of sources not cited by the Times, I offered (March 2, 2012) a comprehensive documenting of violence in Darfur generally and West Darfur specifically. Nothing I found comports with the Times’ account, a fact I had stressed to the Times’ journalist in an interview he conducted with me before publishing the Nyuru dispatch.

What I offer here is an annotated time-line from the beginning of 2012 that should make clear just how much the New York Times ignored and how much the world, in turn, has chosen to ignore or discount. The analysis is in two parts: the present account focuses specifically on 2012; Part 2 will offer a more schematic account of what has been forgotten about the years 2013 – 2016.

A Darfur timeline, 2012:

For detailed accounts of individual instances of violence—including village pillaging and destruction, brutal expropriation of farmlands, rape, murder, abduction, and displacement—see the massive archives of Radio Dabanga. Several of my assessments below depend heavily on dispatches from Radio Dabanga (and to a lesser degree Sudan Tribune and UN sources). The events of 2012 are the focus of this Part 1 of a two-part analysis.

January 2012 – present: The aerial military bombardment of civilians and civilian targets has been relentless throughout Darfur, and obscenely destructive. (See updated version of “‘They Bombed Everything that Moved’: Aerial military attacks on civilians and humanitarians in Sudan, 1999 – 2012” | Update, January 12, 2012). There have been many hundreds of such attacks, perhaps thousands—all in clear violation of the banning of offensive aerial military activity by Khartoum, explicitly articulated in UN Security Council Resolution 1591, March 29, 2005). A great many of these attacks are detailed by Radio Dabanga, as well as the more effective Panels of Experts on Darfur.

Khartoum has for decades made use of indiscriminate aerial assaults on civilians in its various wars against the marginalized populations of Sudan; here a recent victim treated by Dr. Tom Catena in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan.

Amnesty International, in the February 2012 report referenced above, also reported on the continuing aerial bombardment of civilians:

Despite the UN Security Council having prohibited all airstrikes and aerial bombardments in Darfur since 2005, the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) have continued to ignore this prohibition with total impunity. Witness testimonies from sites of airstrikes, material evidence of airstrikes, photographs and satellite imagery of armed military aircraft operating from Darfur’s main airports, all indicate that SAF has continued to conduct aerial bombardments and direct-fire airstrikes on both military and civilian targets in all states of Darfur during 2011.

Eyewitnesses indicate that SAF airstrikes in Darfur and elsewhere in Sudan are carried out with Mi-24 attack helicopters and Su-25 ground attack aircraft, while other aerial bombardments are undertaken by Antonov-24/26 transport aircraft converted into rudimentary bombers.

March 2, 2012: On March 2, 2016 I offered a detailed account of violence and the views of human rights and humanitarian organizations for the first months of 2012 and the last months of 2011 (“The Seen and the Unseen in Darfur: Recent reporting on violence, insecurity, and resettlement” | http://wp.me/p45rOG-Ki). Many examples of rape, aerial bombardment, expropriation of land, and destruction of village are instanced, some very close to Nyuru, the dateline for the Times’ dispatch.

Radio Dabanga, for example, reported that a Khartoum official was selling the land of IDPs in Mornei, West Darfur (about 15 miles south of Nyuru):

Residents at internally displaced persons camp at Mornei in West Darfur complained that the land they were displaced from named Bobai Amer is being sold off as residential land. A camp leader said to Radio Dabanga the land which is used for farming, is being sold by Muhammed Arbab Khamis of [Khartoum’s] ruling National Congress Party [as residential land]. (27 January 2012)

The attitude of displaced persons in South Darfur hardly squares with the situation reported by the Times:

Internally displaced persons (IDPs) camps in Gereida, South Darfur have rejected the invitation by the head of the joint UN/African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) Ibrahim Gambari to voluntarily return to their villages. Gereida camp coordinator, Dawood Hagar said IDPs will only consider returning to their villages if there is a guarantee of security.” (Radio Dabanga | Gereida | 23 January 2012)

Here it needs to be understood just how awful conditions were in the camps at the time—and continue to be—and yet still people refused—and continue to refuse—to leave:

A high-ranking United Nations human rights official today said she was shocked at the conditions of a camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Darfur and called for renewed international concern with the situation in the war torn Sudanese region. Kyung-wha Kang, the UN Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights visited the Zamzam IDP camp, which lies on the outskirts of El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur state, and is home to more than 100,000 people. (“UN official ‘shocked’ by conditions in Darfur camp for displaced,” UN News Center, 24 June 2011)

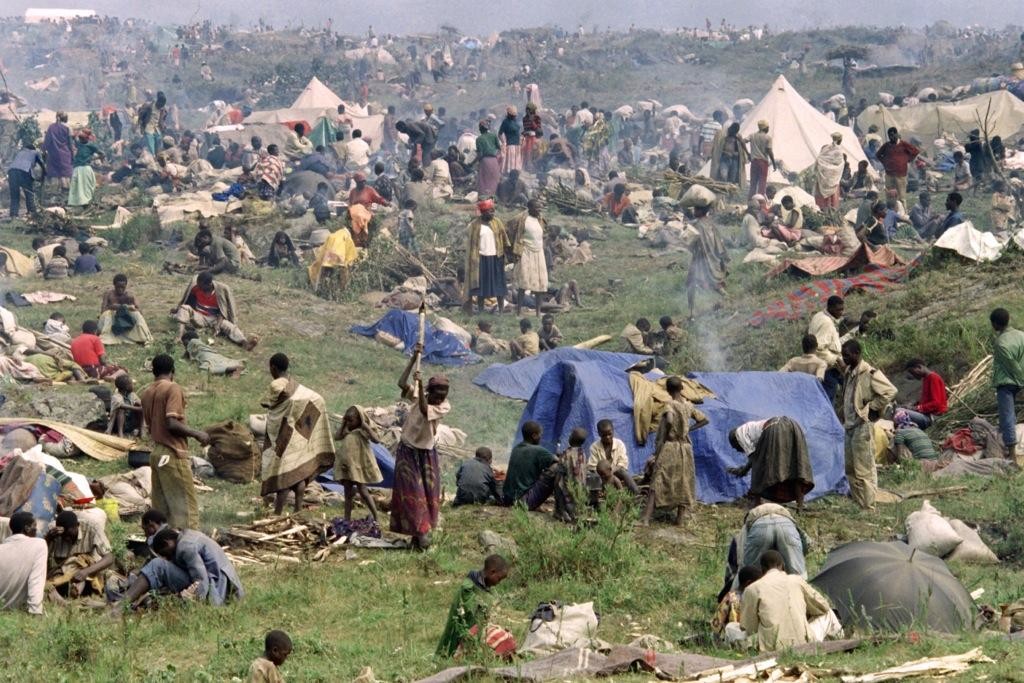

Camp conditions in Darfur are often extremely rudimentary, especially for those newly displaced and most in need

A time-frame for the violence not reported by The Times was provided by the highly authoritative Small Arms Survey (Geneva | January 18, 2012):

The Sudanese government has stepped up hostilities since early 2011, focusing on the Sudan Liberation Army-Abdul Wahid (SLA-AW) stronghold of Jebel Marra and then the Zaghawa-held areas of North and South Darfur such as Shangal Tobaiya, where SLA-Minni Minawi (SLA-MM) draws strength.

Again, we must wonder why this important report was not cited by the Times, especially since a year earlier Human Rights Watch had reported:

“While the international community remains focused on Southern Sudan, the situation in Darfur has sharply deteriorated,” said Daniel Bekele, Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “We are seeing a return to past patterns of violence, with both government and rebel forces targeting civilians and committing other abuses.” (IRIN [Nairobi], January 28, 2011)

Rape continues to be a significant weapon of war, particularly (but not exclusively) by Khartoum’s militia forces—see “Rape as a Continuing Weapon of War in Darfur,” March 4, 2012 | http://www.sudanreeves.org/?p=2884. This is a subject nowhere mentioned in the Times’ dispatch, despite its continuing prominence in defining ongoing violence in Darfur. Radio Dabanga had provided numerous telling examples of rape in West Darfur in the months preceding the Times’ dispatch. Some are included below, along with their distances from Nyuru (again, the Times’ dateline):

• “Woman raped east of Zalingei” | Zalingei, West Darfur (12 January 2012) – On Wednesday a young woman was raped by two armed men near Wadi Dul Beja displaced persons camp, east of Zalingei, in West Darfur. A female source told Radio Dabanga the woman ventured out of the camp with her sister and mother to collect firewood …. [Zalingei is about 50 miles southeast of Nyuru—ER]

• “Girl, 14, raped in West Darfur” | El Geneina (4 January 2012) – A 14-year-old girl was raped by an unknown number of gunmen, near Kandomi displaced persons’ camp in West Darfur, a source told Radio Dabanga. The girl was with four others on the way back to the camp from El Geneina hospital on Monday where they were visiting a relative. [Kandomi/Kondobi camp is approximately 35 miles from Nyuru—ER]

• “Two rapes in West Darfur” | ZALINGEI (29 November 2011) – A refugee [from] West Darfur’s Hassa Hissa camp was raped and killed by unidentified gunmen on Tuesday, a source from Zalingei told Radio Dabanga. The armed group allegedly raped the woman in front of her husband after the evening prayers, when the victim was returning home from the city with her husband. [Zalingei is about 50 miles southeast of Nyuru—ER]

• “IDP raped in Qarsla” | Qarsla (5 December 2011) – An armed group on Sunday raped an internally displaced person from Jebelain camp in Qarsla, West Darfur. A witness told Radio Dabanga that the Gunmen attacked the displaced person while she was working on her farm in Wadi Mara, 3 kilometers south of the camp. He said that the gunmen took turns in raping the displaced person and pointed out that the region has no UNAMID mandate and that no complaint was filed at police as no procedure will be carried out as in previous incidents …. [Qarsla—more commonly Garsila—is about 60 miles southeast of Nyuru—ER]

• “Serial rape crimes in West Darfur: Five women fall victim to armed shepherds in one week” | MORNEI (17 November 2012) – A series of rape crimes were committed in West Darfur’s Mornei region this week, witnesses told Radio Dabanga on Thursday. Two refugee women were raped in Mornei region’s Kabiri Valley on Tuesday, on in Aro Valley on the same day and two others in Mornei refugee camp on Monday. In all cases, armed shepherds were accused of the rapes …. [Mornei is about 15 miles from Nyuru—ER]

• “Sudan: Three Teenagers Raped in West Darfur” | GARSILA (6 November 2011) – An unidentified armed group raped three teenage refugees in West Darfur’s Garsila camp on Friday, witnesses told Radio Dabanga. “Three gunmen took the women from the village of Amarjadid in Western Garsila. The women were aged 14, 15 and 17,” a witness told Radio Dabanga. [Garsila is about 60 miles to the south of Nyuru—ER]

• “Women raped near Eastern Chad refugee camp” | Eastern Chad (30 December, 2011) – Four women from Darfur were raped in Gaga refugee camp in Eastern Chad on Sunday, a source has told Radio Dabanga. The women ventured out of the camp to fetch firewood in the early afternoon when they were attacked by four armed gunmen. A fifth woman suffered a beating but managed to escape …. [Gaga refugee camp is approximately 50 miles west of the Chad/West Darfur border—ER]

Women and girls continue to be the victims of an immense and brutal campaign of sexual violence

May/June 2012 – Violence, expulsion or disabling of key humanitarian workers, and denial of access to the UN human rights investigators all define these months:

“UN rights expert prevented from visiting Darfur” | Agence France-Presse (14 June 2012) The newly appointed UN expert on human rights in Sudan said on Thursday that Khartoum prevented him from visiting Darfur during a five-day trip to Sudan, despite his request to do so. Mashood Adebayo Baderin, at a press briefing in the Sudanese capital at the end of his first visit since being appointed in March, said he was unable to go to the war-torn region because the authorities failed to grant him a travel permit. “We requested that we wanted to visit Khartoum and Darfur, but the time limit I was informed was short to make the arrangements,” Baderin said. “In spite of the assurances from the government that the human rights situation in Darfur is relatively improved, I have received contrary representations from other stakeholders,” he added.

UN expert on human rights in Sudan Mashood Adebayo Baderin, denied access to Darfur by the Khartoum regime

Presumably, if “peace has settled on the [Darfur] region,” as claimed by the Times, Khartoum would be eager to have others witness this new “peace.” Further, why didn’t the Times cite any of the “other stakeholders” in Darfur that Baderin refers to? with views so contrary to those conveyed in the Times’ dispatch?

The need for increased humanitarian capacity because of the large numbers of newly displaced persons has long been well known to Khartoum, which has nonetheless continued to engage in acts of obstruction and a general war of attrition against relief organizations (thirteen had been expelled by the regime in March 2009). On May 22, 2012 MSF announced:

As a result of increasing restrictions imposed by Sudanese authorities, the medical humanitarian organisation Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) has been forced to suspend most of its medical activities in the conflict area of Jebel Si, in Sudan’s North Darfur State. MSF is the sole health provider in the region. “With the reduction of our activities in Jebel Si, more than 100,000 people in the region are left entirely without healthcare,” says Alberto Cristina, MSF’s operational manager for Sudan.

Diminished humanitarian capacity (in the form of so-called “implementing partners”) has badly compromised the work of the World Food Program in Darfur. The following example is entirely typical:

Mornay camp food rations reduced by half | Radio Dabanga, Mornay camp (29 May 2012) – Mornay camp residents have complained that the World Food Programme have reduced food rations by half. A camp leader told Radio Dabanga that the rations were reduced without any explanation from the WFP. He appealed to the WFP to resume full rations and remember the difficulties facing displaced people in buying food from the market, amid food shortages and high prices.

Another significant omission in the Times’ dispatch is the often grim fate of other returning displaced persons noted. Examples such as the following had been reported by Radio Dabanga for years:

“IDPs flee back to camps after new settlers open fire” | El Daein (18 May 2012) Hundreds of displaced people have fled back to Neem camp in East Darfur [formerly part of South Darfur] after new settlers on their original lands attacked them, when they returned with state authorities as part of the programme of voluntary return. Witnesses said on Wednesday the old Neem camp residents were taken with authorities including the state governor to resettle on the land they were originally displaced from. On arrival they said militants started shooting heavily into the air and threatening to kill the returnees if they did not leave the area, even though senior government officials were present.

To be displaced in Darfur

The destruction of non-Arab/African villages has been described my many as a thing of previous years; this is particularly true of UNAMID, the primary source for the Times’ dispatch. This is vicious distortion. There continue to be countless examples of what Radio Dabanga reported in June 2012:

“Residents flee after militants burn down village” | Dali (5 June 2012) – Residents that fled Dali near Kabkabiya have said their village was completely burned down by militias. Witnesses told Radio Dabanga that dozens of residents fled towards Kabkabiya yesterday evening after gunmen attacked killing one resident and wounding several others. They said gunmen traveled on camels, horses and in cars opening fire before setting the village alight. They added that the incident came a day after two people were killed in an exchange of gunfire with militants at a village near Dali.

The burning of African villages by Arab militiamen and Khartoum’s regular SAF troops remains commonplace in Darfur, especially in North and Central Darfur.

Aerial bombardment of civilian targets throughout Darfur has continued relentlessly; on June 5, 2012 I offered another update, with substantial additions of data, to “‘They Bombed Everything that Moved’: Aerial military attacks on civilians and humanitarians in Sudan and South Sudan, 1999 – 2012” (www.sudanbombing.org).

In a May 25, 2012 analysis (“Darfur in the Still Deepening Shadow of Lies”) I examined in detail UN complicity in obscuring Darfur’s realities. My sharp critique has been borne out in detail in a Foreign Policy exposé based on the leaked documentation provided by former UNAMID spokeswoman Aicha Elbasri (“’They Just Stood Watching,’” Colum Lynch | Foreign Policy, April 7, 2014).

July 2012 – Small Arms Survey (Geneva) gives a useful overview of the shifting patterns of violence in Darfur: “Forgotten Darfur: Old Tactics and New Players,” (July 2012). Their report is based on field research conducted from October 2011 through June 2012, and supplemented by extensive interviews, a full desk review of available reports, and a wide range of communication with regional and international actors. The opening paragraphs in their Executive Summary gives a sense of what UNAMID chooses not to see and what the New York Times didn’t bother to consider:

Since 2010 Darfur has all but vanished from the international agenda. The Sudanese government has claimed that major armed conflict is essentially over, that armed violence of all kinds has declined significantly, and that such violence is now dominated by criminality rather than by military confrontation [ ]. This view has been bolstered by statements from the leadership of the joint United Nations–African Union peacekeeping force in Darfur and by those invested in the under-subscribed 2011 Doha Document for Peace in Darfur, who have hailed declining violence and wider regional transformations as conducive to a final resolution of the conflict [citation of statements by Ibrahim Gambari].

Notwithstanding such celebratory assertions [including by the New York Times—ER], Darfur’s conflict has moved largely unnoticed into a new phase. While several parts of Darfur have become demonstrably more peaceful since 2009—particularly as the geography of conflict has shifted eastwards away from West Darfur and the Sudan/Chad border—late 2010 and the first half of 2011 saw a significant offensive by the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and militias, backed by airstrikes and aerial bombardments, targeting both rebel groups and the Zaghawa civilian population across a broad swathe of eastern Darfur.

September – October 2012 – In a portent of what would soon become the norm for North Darfur, and in particular the area known as East Jebel Marra, the village of Hashaba North and its environs (approximately 55 kilometers northeast of Kutum in North Darfur) were attacked from September 26 through October 2 by what were repeatedly described by eyewitnesses as Arab militia forces and Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) aerial military assets. Very high numbers of civilian casualties were soon reported by Radio Dabanga (“between 250 and 300 people,” October 4, 2012), along with repeated descriptions of the attackers on the ground as belonging to “pro-government militias.” Many thousands of civilians were newly displaced.

Even more disturbing and significant, however, was a subsequent attack on the follow-up investigation, a robust UNAMID patrol comprising 16 vehicles in all. On October 17, 2012 a very heavily armed militia group—which had intelligence that allowed it to anticipate carefully the route of the UNAMID convoy traveling to North Hashaba—fired from high ground down upon the highly vulnerable UNAMID forces. UNAMID returned fire, but faced very intimidating weaponry and overwhelming tactical disadvantage; with the killing of one UNAMID soldier and the wounding of three others (one critically), the force retreated back to Kutum.

The UNAMID report, as well as circumstantial evidence, made clear that the attack was carried out by an unusually heavily armed militia force, almost certainly carried out at the direction of Khartoum’s military command. This continues a pattern of attacks either ordered or sanctioned by the Khartoum regime, which has made no secret of its deep hostility to UNAMID and its desire to see the peacekeeping force compelled to leave Darfur.

[See also:

“Darfur: UN Failure and Mendacity Culminate in an Avalanche of Violence,” August 12, 2012 | http://www.sudanreeves.org/?p=3376

“The Avalanche of Violence Continues to Accelerate in Darfur,” October 11, 2012 | http://sudanreeves.org/2012/10/12/the-avalanche-of-violence-continues-to-accelerate-in-darfur ]

“Growing Violence in Darfur Deserves Honesty Reporting, Not More Flatulent UN Nonsense,” 12 December 2012 | http://wp.me/p45rOG-Wv ]

December 2012 – It was clear that despite the judgment of the New York Times (“peace has settled on the [Darfur] region”), 2012 marked a year of massive escalation in the violence in Darfur, if concentrated in some areas in particular. This escalation has continued with the brutal, repeated campaigns against the non-Arab/African populations in East Jebel Marra (2012 – the present) and the Jebel Marra massif itself (January 2016 – present). For lengthy analyses of the violence in East Jebel Marra and Jebel Marra, see:

• “Changing the Demography”: Violent Expropriation and Destruction of Farmlands in Darfur, November 2014 – November 2015″ | December 1, 2015 | http://wp.me/p45rOG-1P4

• “Continuing Mass Rape of Girls in Darfur: The most heinous crime generates no international outrage” | January 2016 | http://wp.me/p45rOG-1QG [Arabic translation of this report | http://wp.me/p45rOG-1Rr ]

In late December 2012 and early January 2013 I offered three lengthy analyses of the security situation in Darfur—all unspeakably grim, all in some sense understatements, given what was impending. They contain a very large number of citations:

Human Security in Darfur, Year’s End 2012: North Darfur: An assessment of the most violent region of Darfur since July 2012 (Part 3 of 3), including the first weeks of 2013 | January 17, 2013 | http://wp.me/s45rOG-3736

Human Security in Darfur, Year’s End 2012: South Darfur | 11 January 2013 | http://wp.me/p45rOG-Y7 and Sudan Tribune, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article45158

Human Security in Darfur, Year’s End 2012: West Darfur

Intolerable human insecurity and threats to humanitarian operations in Darfur remain largely invisible | December 27, 2012 | http://wp.me/p45rOG-Xy

**********************************

Part 2 will examine the years 2013 – 2016, if with a more schematic time-line and less annotation