American Lives, Sudanese Lives: What’s the Calculus in Congress?

The Huffington Post | December 30, 2015

By Eric Reeves | December 29, 2015

In her Pulitzer Prize-winning book “A Problem from Hell”: America and the Age of Genocide (2002), Samantha Power—now U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations—reports a remarkable exchange between Roméo Dallaire, force commander of the painfully reduced UN peacekeeping mission in Rwanda during the 1994 genocide, and a U.S. military officer. On July 29, 1994 President Bill Clinton had ordered, with disgraceful belatedness, 200 U.S. troops to the airport of the capital city, Kigali. Ahead of their arrival, Dallaire reported that a U.S. military officer had called him, “wondering precisely how many Rwandans had died” in the genocide:

Dallaire was puzzled and asked why he wanted to know: “We are doing our calculations back here,” the U.S. officer said, “and one American casualty is worth about 85,000 Rwandan dead.” [footnote 94, with further details]

Roméo Dallaire, commander of the UN mission in Rwanda, 1993 – 1994

As President, Bill Clinton was a significant part of the terrible international failure to respond to the genocide that Dallaire had been warning of for months before April 7, 1994. As Americans, we were all disgraced.

“One American casualty is worth about 85,000 Rwandan dead.” This was the calculus that prevailed in the wake of the Mogadishu (Somalia) disaster of 1993, when, during the notorious “Black Hawk Down” events of October 3 – 4, eighteen American soldiers were killed.

But long after the painful failures of Rwanda, American political leadership—this time in the Congress—seems to be working with the same ghastly calculus. In the vast, 2,000-page omnibus spending bill of December 2015, much was buried in a bill largely compiled by House Speaker Paul Ryan. There were many odious features of the bill, many shameful trade-offs and trade-outs. But in the end, members of both the House and Senate faced an up-or-down vote, with no possibility of amendment. There was enough in the bill to satisfy enough members of both parties, and it passed quickly passed and was promptly signed into law by President Obama before he headed to Hawaii.

House Speaker Paul Ryan, chief architect of the omnibus spending bill that pointedly excluded the possibility of restitution for Sudanese harmed by BNP Paribas’ criminal financial assistance to the Khartoum regime

It took some time for journalists to isolate what they thought were the most egregious provisions of the bill, although liberal and conservative pundits were soon creating idiosyncratic “top ten lists.” But receiving very little attention were the sections of the bill that dealt with various restitution monies, present and future, that will be controlled by the Department of Justice (DOJ) (Sections 404 and 405). These had particular implications for the conviction of French banking giant BNP Paribas (BNPP) for criminal financial abuses of the American financial system (indeed, BNPP is explicitly referred to in Section 405). In May of this year, BNPP was ordered to pay almost $9 billion in forfeitures and fines—of which DOJ set aside $3.8 billion as a restitution fund for those “harmed” by BNPP’s financial crimes.

CEO of BNP Paribas, Jean-Laurent Bonnafé

Since the bank’s criminal actions had benefited primarily the National Islamic Front/National Congress Party regime in Khartoum (Sudan)—at least within the “window” defined by the facts as presented by DOJ in the BNPP case (2002 – 2008)—I and others felt that some significant portion of these monies should benefit Sudanese so clearly harmed, and still harmed, by the financial and economic benefits that accrued to this brutal regime (some 72 percent of BNPP’s criminal financial activity benefited Khartoum, most of the rest benefited Cuba—no longer on the U.S. list of “State Sponsors of Terrorism,” as Sudan very much is). Notably, an arrest warrant has been issued by the International Criminal Court charging President Omar al-Bashir with genocide—the crime that the U.S. seemed so unwilling to confront in 1994.

Khartoum’s génocidaire-in-chief, Omar al-Bashir

I argued the case for Sudanese restitution in the New York Times (July 14, 2015), shortly after the final disposition of the case by U.S. District Court Judge Lorna Schofield in May of this year. Sudanese in many regions of the country—including what is now South Sudan, as well as more than half a million refugees in neighboring countries—have been on the terrible receiving end of the military acquisitions enabled in significant part by BNPP’s criminal actions on behalf of a regime distinguished by an utterly ruthless survivalism.

In retrospect, however, I fear that my efforts and those of my colleague Eric Cohen in putting forward a plan for Sudan Community Compensation only spurred American litigators and their lobbyists to accelerate their own plans for the restitution monies—from BNPP and other similar convictions. And clearly they were successful, for the bill provides explicitly that no money be provided under the terms set out by the DOJ (i.e., to those actually “harmed” by BNPP’s criminal financial activity); all money will go to Americans and their families harmed during past or future terrorist attacks. The bill even goes so far as to stipulate that lawyers will get “no more” than 25 percent of fees for litigation on behalf of their clients. That provision will allow big-time litigators to collect $950 million from the BNPP settlement, while the bill prevents even one penny of compensation for the actual victims.

Nothing will go to the actual victims of the vast majority of BNPP’s criminal actions, the people of greater Sudan, despite predictably very strong support for our proposal by Sudanese around the world.

In other words, it doesn’t matter whether the terrorist acts for which American individuals and their families are to receive restitution occurred within the relevant window of criminal activity: again, for BNPP and its support of the genocidal regime in Khartoum, that means 2002 – 2008. It doesn’t matter that Americans weren’t the victims of BNPP’s crimes: again, these victims were overwhelmingly Sudanese, who continue to suffer from the profligate military and security spending by the Khartoum regime on its genocidal counter-insurgency efforts. None of this matters under the terms of the bill, which in its omnibus nature and wildly diverse provisions—with no chance for amendment—is a conspicuous example of how undemocratic legislation in this country has become, and how insidious the influence of special interests and their lobbyists has become. Former Congressional practices for securing “pork” and adding special interest provisions to bills have now been raised to a high art.

And in the process, the ability of those who would make their case democratically, appealing to large non-Congressional constituencies, has been dramatically reduced. Arguing for the significance of the “harm” done to Sudanese—millions of whom are in need of critical humanitarian assistance—doesn’t have a chance. Indeed, many members of Congress had only a vague idea of many provisions in the omnibus bill—or no knowledge at all until presented with what was essentially a legislative fait accompli.

The omnibus bill gave Americans no chance to hear further our case on behalf of the Sudanese—certainly no chance to suggest that a provision benefiting exclusively a few hundred Americans might be unfair, given the many hundreds of thousands who have died in ongoing genocidal conflict in the Darfur, South Kordofan, and Blue Nile regions of Sudan. We were effectively denied the possibility of arguing that those who had suffered grievous harm, clearly as a result of BNPP’s criminal activity, deserved at least a significant portion of the $3.8 in restitution monies, set aside as such by the Justice Department, in the form of community-based humanitarian relief and development aid to millions of desperate Sudanese.

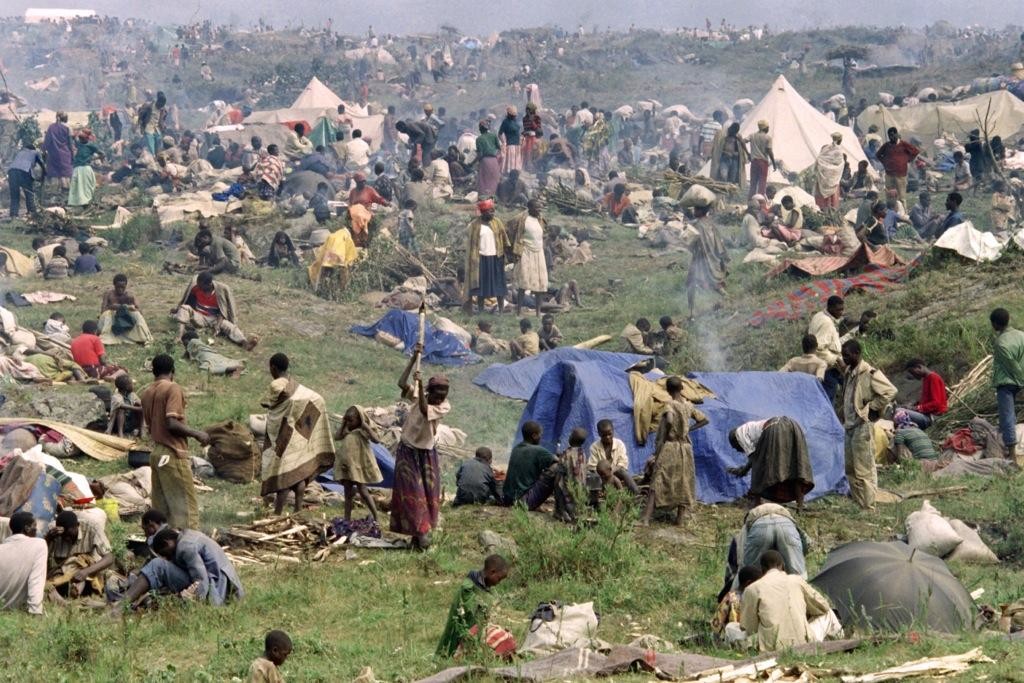

Some of the more than three million people in Darfur who have been internally displaced or forced into eastern Chad as refugees; more than 500,000 people have died in the genocidal violence that began in 2003

In effect, we found ourselves facing another version of the question that was put to Dallaire in Rwanda in 1994: “How many Sudanese have died, or face the threat of dying?” But in the calculus of the omnibus spending bill, the answer wasn’t even that “one American casualty is worth about 85,000 Sudanese dead.” Although many hundreds of thousands have died or are poised to die, the American response this time was “it doesn’t matter how many have died or are at risk: all restitution monies will go to American individuals and their families who are victims terrorist attacks.”

Rwandan refugees in what was the Zaire, now Democratic Republic of Congo

None would quarrel with the argument that restitution monies from the BNPP and other cases should have some provisions for trying to make American individuals and families at least financially whole again. But it also seems to me unlikely that Americans would turn their backs entirely on the hundreds of thousands of deaths and terrible suffering in Sudan, about which the Obama administration for its part has been painfully silent. We will never know how Americans might have decided: an increasingly undemocratic Congress has decided for us.

[Eric Reeves, a professor at Smith College, has published extensively on Sudan, nationally and internationally, for the past seventeen years. He is author of Compromising with Evil: An archival history of greater Sudan, 2007 – 2012 (September 2012)]