“A Better Restitution for Darfur,” The New York Times, July 14, 2015 |

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/15/opinion/a-better-restitution-for-darfur.html?ref=opinion .

The billions seized from BNP Paribas’s money-laundering scheme for President Bashir should go to the people who’ve suffered in Sudan.

By ERIC REEVES

NORTHAMPTON, Mass. — It is now a year since the guilty plea by BNP Paribas, the French banking giant, to charges by the Department of Justice that it had done clandestine business with the governments of Sudan, Iran and Cuba, countries that were subject to economic sanctions. Over the period covered in the indictment, from 2004 to 2012, the amount that was criminally laundered came to more than $8.8 billion, which determined the size of the penalty.

The bulk of these illegal transactions — about $6.4 billion, or more than 70 percent — involved Sudan, whose president, Omar al-Bashir, was indicted in 2009 – 2010 by the International Criminal Court for multiple counts genocide and crimes against humanity in Darfur. The people of Sudan, who continue to suffer terribly under Mr. Bashir’s regime, deserve a significant portion of the penalty assessed.

The most effective way of delivering this restitution would be in the form of increased humanitarian assistance. This could be quickly organized by the United States Agency for International Development.

But what has happened to the $8.97 billion that BNP paid for its criminal actions?

Sadly, the BNP case revealed that the Justice Department had no real game plan for an equitable distribution of the monies from this historic prosecution. Of the vast penalty, financial regulators claimed large portions. The Treasury took $1 billion, while the Federal Reserve received $500 million. Most surprising, and without compelling justification, Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo prevailed on justice officials to allocate nearly $3.3 billion to the coffers of New York State.

Only $3.84 billion remains for restitution. On an arithmetical basis, the Sudanese people should be owed at least 70 percent of this sum, about $2.7 billion. Yet the only mechanism provided by the Department of Justice for dispersing restitution is via individual applications to a little-known website, with a July 30 deadline. In addition, the site’s requirement for documentation of harm suffered sets an unrealistic and unfair standard, even for those in the Sudanese diaspora community with access to the Internet.

At the time of the 2014 settlement, the emphasis in the Justice Department’s lengthy statement was on the deterrent effect of the large penalty and the message sent to other institutions that might be tempted to launder money from regimes blacklisted by the United States. Restitution for the victims was an afterthought, nowhere mentioned in the original announcement of BNP’s guilty plea.

Yet the issue remains central since so many Sudanese clearly meet the criterion set down by the presiding federal district court judge, Lorna G. Schofield: Those deserving restitution are people who have been “harmed directly and proximately” by BNP’s criminal conduct.

All three governments benefitting from the illegal transfers were on the State Department’s list of state sponsors of terrorism (Cuba was removed in May). Some of those harmed by the criminal transactions during the period covered by the suit may be Cuban or Iranian, but few will have faced anything of the order of the genocidal violence suffered by the Sudanese.

BNP’s actions were a huge financial boon to the Khartoum regime, which had previously struggled to find pliant institutions for such illegal transactions even as it tried to meet the costs of hideously expensive wars against its own people. The Justice Department’s criminal complaint against BNP Paribas (which it named BNPP) noted that “BNPP’s central role in providing Sudanese financial institutions access to the U.S. financial system, despite the Government of Sudan’s role in supporting terrorism and committing human rights abuses, was recognized by BNPP employees.”

It’s clear that millions of Sudanese constitute the vast majority of victims harmed by BNP’s criminal conduct, both those who remained in Sudan and the tens of thousands forced into the diaspora or displaced to refugee camps in eastern Chad, Ethiopia and South Sudan, where people languish often in terrible conditions.

The people of the Sudanese regions of Darfur, Blue Nile, South Kordofan, Eastern Sudan and Nubia, as well as the refugee populations in neighboring countries, are clearly those most harmed and most in need of restitution. USAID has the capability to fund relief efforts in all these areas. The distribution of monies should be conducted in close consultation with those in the diaspora, particularly the Darfuri diaspora.

This would be the most reasonable and equitable use of the remaining restitution funds. Among my Darfuri contacts, I have encountered no one who thinks that the Justice Department’s program of administering case-by-case restitution for individual applicants in the diaspora makes sense. These Darfuris believe that the money should go to war-ravaged areas to fund, first, humanitarian and, later, development projects.

The Department of Justice must immediately reconsider its present web-based restitution system, which is set to expire at the end of the month. The humanitarian and relief operations in Sudan (in areas where they are permitted) and among Sudanese refugee camps are grossly underfunded. That is where the BNP money should go.

Eric Reeves, a professor of English at Smith College, is the author of “A Long Day’s Dying: Critical Moments in the Darfur Genocide.”

********************************************

ADDENDUM

We don’t know all the ways in which the Khartoum regime utilized the criminal money-laundering services of PNB Paribas.

But we know something of the men who would have made the key decisions:

President Omar al-Bashir, indicted by the International Criminal Court on multiple counts of genocide and crimes against humanity in Darfur

Former Defense Minister Abdel Rahim Mohamed Hussein: indicted by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity in Darfur

General Bakri Saleh, First Vice President, former Defense Minister, and Deputy Secretary-General of the Islamic Movement

Here are some of their partners in crime:

Georges Chodron de Courcel, chief operating officer of BNP Paribas, stepped down as part of the settlement announced June 30, 2014. The Economist (July 5, 2014) offers the best assessment of the appropriateness of the punishment for a man “serving as the groom to the horsemen of Darfur’s apocalypse”: http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21606279-french-bank-deserved-clobbering-americas-legal-system-looks-extortion

BNP Paribas SA Chief Executive Officer Jean-Laurent Bonnafé, received a 1.2 million-euro ($1.4 million) bonus for 2014, down from 1.58 million euros the previous year and below a 1.88 million-euro target, the bank said in a statement on its website, following a board meeting on February 4, 2015 (Bloomberg, February 9, 2015). Many Sudanese suffered worse hardships.

Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius suggested shortly before PNB Paribas pleaded guilty to criminal money laundering on behalf of the Khartoum regime that transatlantic trade talks were under threat if Washington went ahead with the case. Fabius was, in effect, defending the actions—admitted fully by PNB Paribas—of those abetting genocide: in Darfur, in South Kordofan, and in Blue Nile. So much for the moral integrity of French foreign policy when its banks are caught out in the vilest of criminal actions.

PNB Paribas’s high-priced legal team—forced to watch their client confess to criminal money-laundering on behalf of a genocidal regime

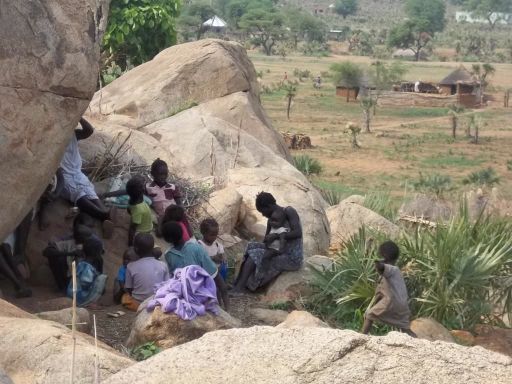

And those who made no appearance in the proceedings of the U.S. District Court (Southern New York) and had no legal team representing them: victims from the regions of Sudan ravaged by Khartoum’s military forces, at least partial beneficiaries of PNB Paribas’ criminal money laundering.

Newly displaced persons in Darfur

People fleeing a village on fire in the Kenjara region of North Darfur

Boy badly injured by indiscriminate aerial bombardment in the Nuba Mountains

Another bombing victim

People have been driven to live in caves in the Nuba Mountains, as relentless aerial bombardment targets their homes and fields

Human Rights Watch has confirmed Khartoum’s use of banned “cluster bombs”—banned because they are viciously indiscriminate, especially as deploy by the regime

Victim of rape—one of many tens of thousands in Darfur, but also South Kordofan and Blue Nile her facial scarring is meant by her assailants to remind all of what has been inflicted (Photograph by Mia Farrow)

People forced to flee Abyei following Khartoum’s military seizure of a region that should certainly have been part of South Sudan had the schedule self-determination referendum been held, per the terms of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (January 2005)

Why does the world allow such signs to remain necessary

Death can be terribly anonymous in Sudan

And grief is everywhere

n