The Obama administration Department of Justice (DOJ) continues in its refusal to answer critical questions about the $9 billion settlement with French banking giant BNP Paribas (BNP) reached in June of last year. Specifically, DOJ refuses to answer questions about its plans for the $3.84 billion that remains for purposes of restitution to those harmed by the criminal actions of BNP—the vast majority of whom are on the ground in Sudan or in refugee camps in neighboring countries.

Seal of the U.S. Department of Justice, with its enigmatic, finally untranslatable Latin motto—perhaps all too appropriate given the Department’s bizarrely inadequate plan to provide appropriate restitution to Sudanese victims of BNP’s criminal money laundering

These are populations in overwhelming need, having endured for years the violent, often genocidal wrath of the Khartoum regime, led by President and former Field Marshal Omar al-Bashir. Al-Bashir has been indicted by the International Criminal Court on multiple counts of genocide and crimes against humanity in Darfur; other regime henchmen have also been indicted for massive crimes against humanity, including former Defense Minister Abdel Rahmin Mohamed Hussein. Their crimes were financially assisted by BNP’s criminal money laundering; BNP is thus complicit in the atrocity crimes by the Khartoum regime that have produced staggering numbers of Sudanese desperately in need.

President Omar al-Bashir

Former Defense Minister Abdel Rahim Mohamed Hussein

Altogether, that number now approaches 7 million if we consider: the highly distressed populations in Darfur (almost 4.5 million people in need of humanitarian assistance); Darfuri refugees in eastern Chad (370,000); Sudanese refugees in South Sudan and Ethiopia (more than 300,000); and the civilian populations of South Kordofan and Blue Niles states, where more than 1.7 million people are live in extremely precarious conditions because of Khartoum’s regular assaults on agricultural production, food stocks, and villages with no military presence. These assaults take primary form as aerial bombardments targeting civilian hospitals, schools, churches and mosques, with a particular focus on areas where planting and harvesting takes place. Khartoum has also placed a complete humanitarian embargo against civilians.

One of countless civilian casualties of Khartoum’s relentless and indiscriminate aerial attacks in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan

Instead of directing the $3.84 billion nominally set aside for restitution primarily to those in Sudan who have been directly harmed, DOJ has evidently settled on a plan by which only Sudanese forced into the diaspora between 2004 and 2012—and to a much lesser extent Cubans and Iranians—will be eligible for settlement monies. The number of Sudanese refugees and exiles who are aware of the DOJ website for registering is likely in the hundreds, and at most a few thousand. And among this population—which must be sufficiently fluent in English and Internet use, as well as aware of the existence of the DOJ website page—there are few who believe that they should be the recipients of the restitution funds: they are well aware of how much human suffering and destruction continues in their homeland. I know of no Sudanese in the diaspora who would not put humanitarian and reconstruction efforts before restitution for individuals.

Despite knowing all this, DOJ persists in its plans, aided in part by law firms with no knowledge of Sudan or the bizarrely unfair focus of the DOJ plan. But again, given all we know, the overwhelming emphasis should be on Sudanese suffering on the ground and in desperate need of assistance, assistance that could be rendered either via of the U.S. Agency for International Development or through grants to non-governmental humanitarian organizations such as Oxfam America, the International Rescue Committee, or Save the Children—all of which have long and distinguished records of providing relief in Sudan, South Sudan, and eastern Chad.

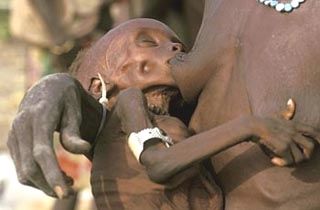

A child whose level of malnutrition is being assessed by means of a MUAC test (“middle upper arm circumference”)

Key UN agencies, many of which are critically underfunded, should also receive the funds necessary to meet the most urgent needs, particularly food. The UN’s World Food Program, for example, has recently suspended its program of food vouchers for the people of Darfur—vouchers that for many families are the difference between a modestly adequate diet and severe, life-threatening malnutrition. The Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) rate for children under five in North Darfur is, according to the most recent UNICEF report, 28 percent—almost three times the emergency threshold for such a population in a conflict zone. North Darfur is presently enduring extreme violence, more often than not directed at civilians, not Darfuri rebels.

North Darfur—the consequences of unrestrained genocidal counter-insurgency

DOJ’s moral myopia is already costing lives; while the $3.84 billion might help a few in the diaspora with access to the DOJ website, it could help millions on the ground in Sudan and neighboring countries with large Sudanese refugee populations. We need only look at the funding shortfalls reported by the UN to see the scale of unmet needs. Perhaps most egregiously, the World Food Program reported last month on its work in Darfur:

Funding for WFP cash and voucher assistance is facing a severe shortfall, with a complete break in funding anticipated from July onwards. WFP estimates the extent of this funding shortfall at almost $24.8 million, including $18.4 million in transfer value for the next six months. In response, WFP has already halted a number of expansion plans and will likely cut rations in some locations for the month of June. If no urgent funds are mobilized however, WFP may have to further disrupt the voucher distribution cycle with more extensive ration cuts or even complete suspension of the programme.

This puts almost 500,000 people, mostly IDPs, at risk of receiving no voucher assistance from September onwards. WFP is urgently requesting donors to make available any additional funds to prevent closure of the programme. (emphasis added)

If there is no food, there will be extreme malnutrition and possibly famine

It is simply shocking that the U.S. Department of Justice gives no sign of understanding the implications of these numbers—numbers that dwarf the benefits that might accrue from the restitution plan currently in place—with a deadline of July 30, 2015, i.e., this week. Members of Congress should express their outrage over this callous and morally lazy refusal by DOJ to reconsider restitution plan for those harmed by BNP’s criminal money laundering—$6.4 billion (more than 70 percent) benefiting the Khartoum regime. Certainly the criterion for judging those who have been “harmed” should remain the one explicitly articulated by the presiding judge in the District Court that oversaw the BNP case: Judge Lorna Schofield defined them as people “directly and proximately harmed by PNBP’s criminal conduct.” This would hardly seem to characterize New York State, even as Governor Andrew Cuomo was able to strong-arm some $3.3 billion from the BNP settlement. DOJ refuses to say whether New York State has received its “restitution,” even as we may be sure that not a dime has gone to assist those suffering in Sudan and its peripheries.

BPN Paribas is the world’s third largest bank

Time is short, and DOJ is giving every sign of continuing its obduracy, stubbornly refusing to respond to any question about the BNP Paribas settlement—even about whether or not they have received the settlement penalty monies from BNP, which the well-capitalized bank could easily have afforded to pay in its entirety. Instead of helping those who need it most, Obama administration officials at the U.S. Department of Justice are engaged in profoundly perverting the course of justice, even as it lies clearly before them. This is disgraceful.

[Eric Reeves, a professor at Smith College, has published extensively on Sudan, nationally and internationally, for the past sixteen years. He is author of Compromising with Evil: An archival history of greater Sudan, 2007 – 2012 (September 2012)]