[This account will be updated as events dictate; all updates indicated as such; updates are ordered by relevance to particular topics, not chronologically—ER] .

[Update, May 23, 2015: Sudan Tribune, May 23, 2015:

[Petroleum minister Stephen Dhieu Dau] said he reassured oil workers and denied the evacuation of oil workers. “The oil workers are there. I met them today and assured them of the capability of the government to provide adequate security. So it is not correct that oil workers have been evacuated. Why evacuate them and the government is control? There is no danger,” he said. This is the first high level visit after heavy fighting in recent days in oil producing areas in Upper Nile state. It was meant to boost the morale of the government soldiers and assure local population. Last Thursday the Chinese official TV announced the evacuation of 400 oil workers from Paloich oilfields in South Sudan due to the ongoing fighting in the oil-rich Upper Nile state territory.]

The oil minister’s claim flies directly in the face of claims by Chinese state television that it has evacuated more than 400+ workers not just from Upper Nile, but South Sudan. Without the skilled workers necessary to maintain production, the oil infrastructure and pipeline will soon become inoperable. See Sudan Tribune dispatch below.

[Update, May 26, 2015:

Luke Patey, highly informed author of The New Kings of Crude, on China, India and Oil in Sudan/South Sudan, writes of the Upper Nile oil fields: “Chinese engineers [are] still on site with skeleton staff despite the evacuation. But production will suffer if there is no speedy return.”]

The fighting that is now occurring in the oil regions of Upper Nile, South Sudan has created dangers greater than at any time since the outbreak of violence in mid-December 2013. There is very little news reporting at present, but a range of reliable sources on the ground paint the grimmest of pictures. While the situation remains fluid, the preponderance of evidence and some highly authoritative reports suggest that it is only a matter of time before the Adar Yel and Paloich oil fields are shut down by fighting. Bloomberg reports (May 21, 2015) that workers evacuated to Juba from Paloich have returned; but the sources for this and what few news reports there have been depend excessively on the claims of the parties to the conflict, who have frequently made expediently false claims. In any event, it is important to remember that shutting down an oil pipeline and related infrastructure are complex tasks, which if not performed correctly with adequate time, can result in tremendous damage, both the pipeline and infrastructure, as well as the local environment.

[Update, May 22, 2014: Today’s Sudan Tribune reports:

The Chinese government announced it has conducted mass evacuation of its oil workers from Paloich oilfields in South Sudan due to the ongoing fighting around the oilfields in the oil-rich Upper Nile state territory. Heavy fighting between troops loyal to president Salva Kiir and the armed opposition faction (SPLM-IO), led by former vice president, Riek Machar, has continued near the oilfields since Tuesday. In a statement announced in Beijing on China’s national television (CCTV) on Thursday, it said the decision came due to the insecurity around the oilfields resulting from the advance by the rebel forces towards the oilfields.

It said the Chinese embassies in both Khartoum and Juba with China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), a government owned major oil company operating in Paloch, have already evacuated over 400 Chinese oil workers from the conflict area. “More than 400 Chinese oil workers have been evacuated from South Sudan due to growing violence,” said the statement published by the Chinese government. Beijing said the evacuated workers will be flown to China in the next few days. This latest development largely contradicts South Sudan government’s claim on Thursday that oil workers were returning to Paloich allegedly after defeating the rebels.

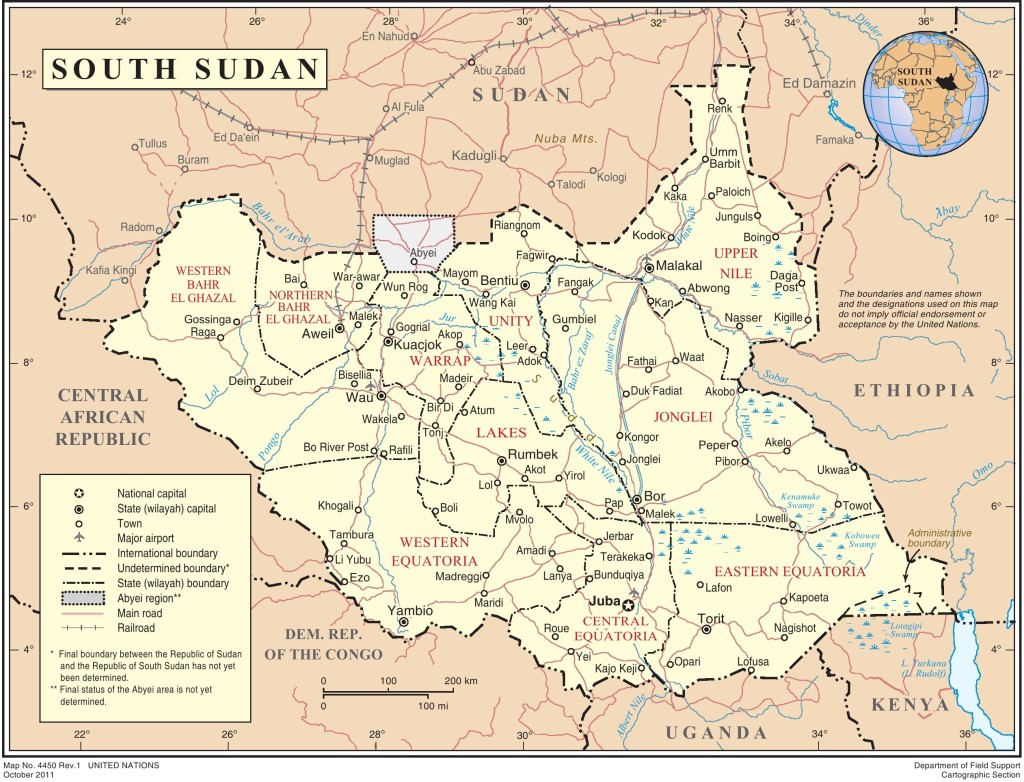

Map of South Sudan; Upper Nile is in the northeast section of the country

It is clear from all reports that “General” Johnson Olony has sided with the rebel forces of the SPLA/In Opposition (SPLA/IO), nominally led by Riek Machar. The degree of Riek’s command and control over opposition forces is unclear, but is certainly far from complete. Indeed, Olony has declared publicly that his primarily Shilluk force will operate independently of the SPLA/IO, with a primary goal of protecting regions in which Shilluk populations are concentrated. But this is belied by what is his apparently central role in the impending assault on Adar Yel and Paloich, the two critical points in the oil region of Upper Nile. His forces also apparently control Malakal, which was retaken from the SPLA/Juba several days ago.

[Update from Juba: 3pm EDT, May 21, 2015:

A highly informed source indicates that Olony may have suffered a significant military set-back in Malakal and has requested of Khartoum an airlift to safety. The same source reports that Malakal is now largely back in SPLA/Juba hands, although elements of Riek’s forces remain in the strategic town. This is so despite Olony’s claim of May 19 to be in complete control of Malakal.]

[Update: May 25: The most recent reports indicate that Malakal remains under the control of opposition military forces, although the SPLA/Juba is apparently closing in on re-capturing the town; the fate and location of rebel leader Olony are unclear. Melut town is under the control of SPLA

Heavy fighting is reported in Upper Nile—from Renk in the far north to Malakal in the south, to several areas in the east. This includes substantial use of tanks, artillery, mortars, heavy machine-guns, as well as a great many smaller automatic weapons. Although the rainy season will soon be upon the region, a provisional fate for the oil regions appears may well be decided in the coming days.

[Update, May 25: Reports of fighting across much of South Sudan are increasing, as is the chaotic nature of the fighting. Much of it is simply for criminal purposes; much of it reflects inter-ethnic animosities and have spread with the violence.]

Not only does this suggest that there will be no end to fighting between the various elements of the SPLA/IO (including Olony’s forces) and the SPLA/Juba, but that retaliatory ethnic violence will follow around the country. There are already reports from Juba, for example, that Shilluk have been targeted and attacked, with many fleeing. There are also serious questions about some of the key components of larger SPLA/Juba military units in Upper Nile: the majority of soldiers in at least one key unit, according to a source in Juba, are Nuer and Shilluk and may desert to the SPLA/IO. SPLA/Juba may find that both their tactical and strategic efforts are badly compromised by such defections.

The heaviest fighting is reported to be at Melut, on the Nile River, approximately 40 kilometers to the west of Paloich. If Melut falls to the SPLA/IO, it is unlikely that the SPLA/Juba will be able to retain control of the oil fields. SPLA/Juba military spokesman Philip Aguer today declared:

“The SPLA eliminated the threat to Paloich and the oilfields by defeating the rebels yesterday,” army spokesman Col. Philip Aguer told Anadolu Agency. “We have recaptured the town of Melut less than 24 hours after the rebels entered it.”

But this account does not comport with other, more disinterested accounts. Based on the evidence available, I believe the oil fields may soon be shut down and that the workers who have already been evacuated once will be evacuated again, and will not return for the foreseeable future. And if the SPLA/IO should take firm military control of the oil fields—an unlikely development but certainly possible—it is an open question as to whether the skilled oil workers necessary to re-start the oil flow will return at all.

[Update: May 22, 2012, 10:am EDT:

There is now independent verification that Melut is completely under that control of the SPLA/Juba.]

This raises a question that has been in play since fighting took on a national character in South Sudan shortly after the events in Juba in mid-December 2013: what will be the response of the Khartoum regime to the halting of the flow of oil from Upper Nile, from which it derives critical transit fees, one of the last remaining sources of hard currency the regime has? Such transit fees are paid both by the foreign oil companies that built and control the oil fields of Upper Nile (essentially China and Malaysia) as well as by South Sudan. But if South Sudan is denied oil export revenues because of a shutdown in oil production and transit, the Government of South Sudan will of course make no further payments to Khartoum.

Khartoum’s response

Minutes from an important meeting of senior regime officials on August 31, 2014 make clear the desire to assist militarily—in strategically significant ways—the SPLA/IO (for commentary on authenticity of these minutes, see http://wp.me/p45rOG-1w5). Excerpts appended to the end of this dispatch make clear the extent of this assistance.

Collectively, the leaked minutes from meetings on July 1, 2014, August 31, and September 10, 2014 suggest the very real possibility of Khartoum’s takeover of the oil regions; at the very least the regime wants to see a weakening of South Sudan by having, yet again, Southern fight against Southerner.

[Update: May 22, 2015:

Associated Press reports today South Sudan’s claim that Khartoum is militarily assisting the rebels in Upper Nile. There has certainly been assistance in the past: the question is whether this represents an escalation in Khartoum’s involvement in the fighting. See [3] below.]

Economic pressures on the regime, and the threat of civil insurrection, are enormous. Since August of last year, the economy in Sudan has continued to implode under the pressures of high inflation, high unemployment, gargantuan external debt with fewer sources of loan guarantees, a rapidly declining currency, and an almost total lack of foreign exchange currency. It is this last that may force the regime’s hand: bread lines and shortages, as well as shortages of cooking fuel, have been reported for over a year: there simply isn’t enough hard currency with which to buy wheat for flour or fuel for cooking. The agricultural sector in Sudan has declined precipitously during the twenty-six-year rule of the National Islamic Front/National Congress Party regime, and this only exacerbates the food shortages. Malnutrition is running at shockingly high levels throughout much of Sudan, especially in Darfur, eastern Sudan, the Nuba Mountains, and Blue Nile State.

If the regime does nothing, oil production may well be halted soon. If the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) cross into South Sudan to seize the oil regions of Upper Nile in order to re-start the flow of oil, it will completely abrogate the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, and sooner or later—likely sooner—lead to war between Sudan and South Sudan. The SPLA/North (in South Kordofan and Blue Nile) will likely make common cause with SPLA/Juba, their former comrades in arms. The SAF will be regarded by both as a mortal enemy, as it is now by the SPLA/North, which has again withstood the worst that Khartoum can throw at them during this second dry season “Final Campaign.”

Neither IGAD, the East African regional intergovernmental body, nor “IGAD+”—nor the UN or African Union—seem to fully understand these risks, or the consequences for the region of renewed war between Sudan and South Sudan. There has, for example, been no pressure on Khartoum to halt its assistance to the SPLA/IO, or to close the SPLA/IO training bases in South Kordofan. The Obama administration and the EU both seem helpless, with neither diplomatic vision nor an understanding of what pressures might actually affect the situation on the ground. The much-threatened sanctions against individuals will have little impact, particularly on people like Olony and Peter Gadet (responsible for shooting down a UN transport helicopter last August), and risk being disproportionately or erroneously applied. Many of the men putatively targeted do not operate in any meaningful chain of command, and do not leave South Sudan in any event. They are impervious to sanctions.

Without pressure on Khartoum to stop its interference in the military events in South Sudan, no arms embargo or other punitive measures can be equitable. Denying the combatants weapons and ammunition will be key, but will not work if perceived by Juba as one-sided in consequence. What is much more important is that the international community have at the ready a vigorous response to any military incursion into Upper Nile by Khartoum’s forces.

On the ground, reconciliation, if it comes, will come slowly and region by region. The South Sudan Council of Churches has begun in earnest with this task, but it will require a great deal of civil society assistance. The major military actors have been put on notice that they will be held accountable for the atrocity crimes that have defined the violence for almost a year and a half; to date, such threats seem to have had almost no impact on either Riek Machar and his generals, or on Salva Kiir and the men who surround and advise him.

[Of particular note in the chronicling of human rights abuses by Amnesty International today (“South Sudan: Escalation of violence points to failed regional and international action,” May 21, 2015), attached below as [2].

There are no easy answers to the crisis that has now developed and grown terribly in South Sudan; no “silver bullet” or obvious negotiating strategy. Tragically, men with guns are making the critical decisions for all the people of South Sudan, who are suffering terribly, with famine looming and more than 1.5 million people displaced from their homes (see [3] below). Creative, robust, truly international diplomacy—sustaining pressure while not setting artificial deadlines—is the greatest hope for peace in South Sudan. But it will not come quickly or easily. What is certain is that the crisis requires a good deal more attention and policy thought than it is presently receiving.

*************************

[1] From minutes recording comments by senior military officials in Khartoum, August 31, 2014: on assisting Riek Machar and rebels in opposition to Juba (all emphases added):

• General Imad al-Din Adawy, Chief of Joint Operations:

We [in the regime] suggested [to Juba] the formation of joint forces along the border line, but they refused that too. They are still supporting the two divisions of Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile. Accordingly, we must provide Riek’s forces with great support in order to wage the war against Juba and clean the whole of Greater Upper Nile area.

• Lt. General Hashim Abdalla Mohammed—Chief of Joint General Staff:

We must change the balance of forces in South Sudan. Riek, Taban [Deng], and Dhieu Mathok came and requested support in the areas of training in military intelligence and especially in tanks and artillery. They requested armaments also. They want to be given advanced weapons. Our reply was that we have no objection, provided that we agree on a common objective. Then we train and supply with the required weapons.

• Lt. General Abdel Rahman Mohamed Hussein—Minister to Defense:

I met Riek, Dhieu and Taban and they are regretting the decision to separate the South and we decided to return his house to him [Riek long lived in Khartoum following his defection from the SPLA]. He requested us to assist him and that he has shortage in the military intelligence personnel, operations command and tank technicians. We must use the many cards we have against the South in order to give them unforgettable lesson.

• Lt. General Bakri Hassan Salih—First Vice President:

We are not interested in any relation with South Sudan or the neighboring countries, but it is a reality that requires us to respond and deal with it. Dr. Riek paid me a visit on August 11, 2014. He said the Dinka exterminated his tribe. He requested assistance. The president [Omar al-Bashir] accepted to host a liaison office.

[These minutes have been authenticated by a wide range of Sudan and regional experts: see http://wp.me/p45rOG-1w5 ]

[2] Amnesty International:

South Sudan: Escalation of violence points to failed regional and international action

New research conducted by Amnesty International on the surge in military activity in South Sudan over the past weeks clearly shows that regional and international efforts to end the human suffering caused by armed conflict in South Sudan have failed.

Amnesty International researchers have just returned from Bentiu in Unity state where they documented violations including civilian killings, abduction and sexual violence.

“The spike in fighting between the parties to the conflict is a clear indication that South Sudan’s leaders have little interest in a cessation of hostilities, while the region and the rest of the international community are reluctant to take bold steps towards addressing repeated atrocities,” said Michelle Kagari, deputy director with Amnesty International.

Thousands of people have fled to the United Nations base in Bentiu to escape intensified fighting in Unity state between the Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army-In Opposition and government forces and allied youth and militia groups.

Individuals who fled violence in Rubkona, Guit, Koch and Leer counties consistently described government forces, some in SPLA uniform and others in civilian clothing, mostly from the Bul section of the Nuer ethnic group, attacking their villages armed with axes, machetes and guns.

The interviewees gave chilling accounts of the government forces setting entire villages on fire, killing and beating residents, looting livestock and other property, committing acts of sexual violence and abducting women and children.

A 45-year-old woman told Amnesty International that government forces reached Panthap, in Rubkona county, early on the morning of 8 May. They instructed villagers to bring out all their property and took away anything of value. She said they beat her with a stick, but no one was killed. She fled with approximately 200 other villagers, arriving at the UN camp for displaced persons in Bentiu on 12 May.

A woman from Chatchara, in Rubkona county, described an attack on her village by groups of young men she believed were allied with the government on the morning of 7 May.

“They came and said, ‘bring your property out,’ and then they burnt our tukul [thatch-roofed mud structure]. They beat us with sticks and metal rods, saying ‘where are the boys and young men?’ They took our property, our maize and clothes, and forced us to carry them towards Mayom. We were many women from the village. One woman got tired and was killed. They also shot her two-year old daughter.”

The woman was eventually freed. She too made her way to the UN camp in Bentiu.

A 70 year-old man, also from Chatchara, similarly described beating, burning and looting by the government forces:

“When the SPLA arrived, they beat me and set fire to my three tukuls, and all the tukuls in the village. They took the cows and goats. Some children were shot in the crossfire. Many women and children were killed. I saw young children and women taken and forced to drive the cows and goats. They took my granddaughter, a girl of 13 or 14 years.”

A 20 year-old woman from Guit county recounted how a group of armed SPLA soldiers and youth attacked her village on the night of 7 May:

“They even killed young children and old men. They set the granaries, where we keep maize, on fire. They came to my house and shot my nephew who was about 20 years-old. They beat my mother with a rope used for tying the cows. They were asking her, ‘Where are the young men, we want to kill them, they have joined the opposition.’ I took off running with my three children and two siblings. We ran to the river while they were shooting at us. From the river, I saw them burn the house. They also took our cows and goats—we had 15 cows and 30 goats.”

The woman said four men raped her 23-year-old cousin, a mother of two. “I saw her when I was running. She was screaming,” she said. She also said that the attackers abducted her 13-year-old sister and her 15 year-old brother. She does not know the fate of her husband, mother or disabled uncle, whom she left behind in their home. “My whole family is lost,” she told Amnesty International researchers.

Nyanaath, a mother of three, said that government forces attacked her village in Guit county at midday on 10 May. She said the attackers, some of whom were in uniform, stole cows, looted property and set all the tukuls on fire.

Nyanaath said the attackers then raped women, herself included. She told Amnesty International that soldiers took her, pushed her on her back and pulled down her underwear. One started raping her while another pointed his gun at her. She also said she saw 10 boys and girls, aged between 10 and 13, being abducted by soldiers.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) says some 100,000 people have been displaced by the recent fighting in Unity state. About 2,300 civilians, mostly women and young children, have sought refuge at the UN base in Bentiu since 20 April, joining over 50,000 others who have fled there since the start of the conflict in December 2013. More are on their way.

Government forces have blocked others at checkpoints, preventing them from reaching the safety of the base. Thousands have fled into the bush or swamp areas.

The UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) reported that at least 28 towns and villages in Unity state were attacked in the space of two weeks, between 29 April and 12 May. Civilians were targeted and their property was looted.

“These attacks on civilians in Unity state, and the ensuing displacement, mirror events documented by Amnesty International in early 2014. The fact that some of the same villages and towns are being subjected to a repeat round of atrocities underlines the need for the African Union, the UN and other international bodies to match their tough rhetoric with concrete action to reduce the human costs of the conflict,” said Michelle Kagari.

“There must be a credible threat of accountability to deter those who carry on committing atrocities with total impunity, a comprehensive arms embargo to halt the flow of weapons that further fuel the conflict and targeted sanctions to provide a deterrent to those who continue violating international law,” said Michelle Kagari.

Amnesty International is calling for:

The UN Security Council to impose a comprehensive arms embargo against all parties to the conflict in South Sudan.

The UN Security Council to move quickly to impose asset freezes and travel bans against individuals and entities who have engaged in violations of international humanitarian law and violations and abuses of international human rights law.

The UN Security Council to make public and act upon a paper outlining options for accountability that Security Council members reportedly discussed on 12 May.

The AU Peace and Security Council to reverse its decision to shelve the report of the Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan pending the finalisation of a peace agreement, to consider the report during the AU Summit in June and to make it public.

The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), to quickly reconvene parties to the conflict and impress upon them that they are bound by commitments to abide by international humanitarian law incorporated within the 23 January cessation of hostilities agreement and recommitted to on numerous occasions over the past year, and to act on its repeated threats to impose targeted sanctions and an arms embargo.

[3] (Associated Press [Kampala, Uganda] May 22, 2015

South Sudan’s military Friday accused the Sudanese government of aiding a new rebel offensive in the southern country where oil fields are now threatened by fresh fighting.

The recent defection in South Sudan’s Upper Nile state of a key general to the rebel side was likely tied to incentives from Sudan’s government, including weapons and ammunition, South Sudanese military spokesman Col. Philip Aguer told The Associated Press. The general, Johnson Oloni, had previously been a member of the government’s military alliance against rebel forces loyal to former South Sudan Vice President Riek Machar, whose fighters control some parts of South Sudan and are pushing to seize oil fields.

“Sudan doesn’t just have a hand in the fighting, it has both hands in this,” Aguer said by phone from the South Sudanese capital of Juba. It’s not the first time South Sudan is accusing its neighbor of supporting rebels, charges routinely denied by Sudan’s government in Khartoum.

Fighting has recently escalated in the states of Unity and Upper Nile, where the last remaining functional fields are threatened by rebels who said this week their goal is to seize the oil hub of Paloich. South Sudan’s military later said the rebels had been repulsed but acknowledged fighting is ongoing in nearby counties. If Paloich were to fall to the rebels, it would be a disaster for President Salva Kiir’s government, which depends heavily on oil revenues to pay its bills.

Thousands of civilians are trapped in the fighting, many of them fleeing to unsanitary swamps as aid workers shut down their facilities and pull out. Doctors Without Borders described an “alarming humanitarian situation,” saying masses of people are hiding in the bush and that the “lack of access to the injured and displaced puts the lives of many South Sudanese at critical risk.”