A startling title from an Agence France-Presse dispatch tells us too much about attitudes and capacity in South Sudan: “50,000 and not counting; South Sudan’s war dead” (15 November 2014):

Missing from the conflict is a clear death toll, as nobody—not even United Nations peacekeepers—has been keeping count. The International Crisis Group (ICG), a conflict think-tank, estimates at least 50,000 people have already died but it admits the true figure could even be double that. It also says the failure to count the dead is a scandal—both as a dishonour to the victims and as something that has kept the country’s suffering off the international radar. [The entire text appears below as Appendix One; all emphases in all quoted text has been added—ER]

This “failure to count the dead” is indeed a scandal, and for precisely the reasons ICG indicates: this failure “dishonours the victims” and “has kept the country’s suffering off the international radar.” If in fact some 100,000 South Sudanese have died, we should know this—and it should make a difference in shaking the conscience of the international community. This is especially true given how tenuous the humanitarian situation remains, how close to famine the country remains, and how an upsurge in fighting this dry season could bring catastrophic mortality.

Mortality in Darfur

But Darfur represents an even more egregious failure to count the dead. And this failure ultimately bespeaks a kind of contempt, not merely a dishonoring of the dead. The last official UN figure on mortality in Darfur was offered in April 2008 by John Holmes, then UN Under-secretary for Humanitarian Affairs: 300,000 dead. But this was not the result of a mortality analysis, new data, or new studies; a BBC account of the press interview in which Holmes announced the figure is revealing:

Mr. Holmes gave the revised total to a meeting of the United Nations Security Council in New York. Sudan disputes the figure, saying 10,000 are now known to have died. The previous figure of 200,000 came from a 2006 study by the World Health Organisation. It included those killed in the fighting itself as well as people who died from disease and malnutrition because of the conflict. The 2006 figure “must be much higher now—perhaps as much as half again,” Mr. Holmes said. He said the new total was an extrapolation from the previous figure and was not based on a new study. (“Darfur deaths ‘could be 300,000,” 23 April 2008)

Shortly after the WHO report was released in 2006, I asked a senior UN official deeply involved with preparation of the report when he expected another mortality study would be conducted. His response? “Never!” The hostility of the Khartoum regime to the WHO efforts of 2005 and 2006 had been so great, so threatening that it would be impossible to imagine conducting any further studies, he informed me. And so there have been none. As Holmes stresses in his crude estimate: “the new total was an extrapolation from the previous figure and was not based on a new study.”

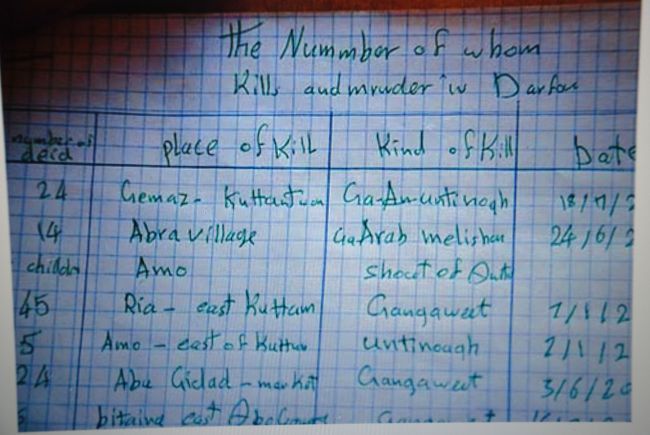

Darfuris in eastern Chad attempt crude calculations of number of dead, type of violence, location; they are doing more than the UN appears willing to do

In other words, there has been no statistical or epidemiological effort by the UN to estimate the number of casualties in the Darfur conflict since 2006—eight years ago. And the most “recent” estimate—constantly cited by news organizations of all sorts—is six years old and represents nothing more than a crude extrapolation: “The 2006 figure ‘must be much higher now—perhaps as much as half again.'”

How many have died in the past six years? How accurate was the UN’s 2006 estimate, which lacked a great deal of the data sought? Is Holmes’ crude extrapolation—simply increasing the old figure by fifty percent because two years had passed since it was published—reasonable when we are speaking of hundreds of thousands of lives? What the International Crisis Group says about mortality in South Sudan is even more true of Darfur: “the failure to count the dead is a scandal—both as a dishonour to the victims and as something that has kept the country’s [Darfur’s] suffering off the international radar.”

Driven by this sense of our “dishonoring” the victims of the Darfur genocide, I made repeated attempts through August 2010 to gather more data, more reports, more anecdotal evidence, and to devise a more adequate methodology in a situation that resisted all traditional epidemiological mortality techniques. This required at various points making assumptions—always in my view conservative, given what we knew at the time—collating all the data at hand and devising a straightforward methodology that could accommodate all these data. Thus while I was able to incorporate important data from the only other significant mortality study since 2008—that of the Center for Research on the Epidemiology (CRED) in Leuven, Belgium (January 2010). Just as importantly, I was able to incorporate extremely significant data collected and meticulously analyzed by specialists for “Darfurian Voices” in Eastern Chad, July 2010.

[Bibliographic information for the CRED study: Olivier Degomme and Debarati Guha-Sapir, “Patterns of mortality rates in Darfur conflict,” The Lancet, January 23, 2010 (pages 294-300) http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2809%2961967-X/abstract]

In the course of using data from the report by “Darfurian Voices,” I was also able to offer a correction to CRED’s gross misrepresentation of violent mortality in the first year of the genocide (particularly February 2003 to August 2003, this on the basis of a widely discredited U.S. State Department document that has been withdrawn from the department’s website). While persuasive in its use of very considerable data about death from malnutrition and disease, CRED offers a preposterous figure of 1,000 – 4,500 deaths for the period February 2003 through August 2003. The simple truth is that CRED has no mortality data of any sort in its database for 2003—for any Darfur state—during this, the most violent year of the genocide to date. Other critical weaknesses are outlined in my August 2010 mortality study, a key section of which appears below as Appendix Two). Lacking data for 2003, the authors play fast and loose with their timeline and whether 2003 appears in the language of the study (sometimes it does, sometimes it doesn’t). They wanted the period covered to run from 2003 – 2008; but without data for 2003, this is nonsense.

[When I questioned author Guha-Sapir at a conference on Darfur (Rockefeller Institute, Bellagio, April 2012), she was unable to explain the critical dating problems I pointed out.]

My own study was the culmination of a dozen previous efforts addressing the question of human mortality in Darfur and eastern Chad (omitted entirely by the CRED study). In my view, based on all extant research and data, the number of dead in August 2010 was very approximately 500,000 (as likely to be higher as lower). I have been unable to find any but anecdotal reporting subsequently, and nothing that would allow me to update the August 2010 finding in a significant way. We do know, however, from many reports by Radio Dabanga and Sudan Tribune, that casualties of war have been enormous, not only from violence—military assaults, murder, continuing displacement, and brutal rapes that are too often fatal, especially for younger girls—but as in the early years of the genocide, from mortality that is the consequence of that violence and violent displacement, including malnutrition, dehydration, and disease (from the very beginning of the Darfur conflict, displacement and violence have correlated extremely highly).

Where is the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations?

Over the past four years tens of thousands of Darfuris have died as a consequence of what has become “genocide by attrition.” But we have no idea about how many tens of thousands have died. For the UN/African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) has proved itself hopelessly inadequate in reporting on rape, mortality, aerial bombardment of civilian targets, and many others forms of violence that have made Darfur today more insecure than at any time since the early yeas of the violence that began over a decade ago. And while the African Union, particularly the leaders of UNAMID and the African Union Peace and Security Council, is most culpable on the ground, it is the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations that must bear primary responsibility in allowing the international community to view UNAMID as somehow a functioning peacekeeping force. It is not—and Hervé Ladsous, head of UN DPKO, deserves a great deal of the blame for not frankly acknowledging the fact. He has not made clear enough, to either the Secretariat or the Security Council, the scale of UNAMID’s failures, even as UNAMID will go down in UN peacekeeping history as the largest, most expensive, and least effective operation to date.

Ladsous is of course aware of the failures that have been regularly reported. He is aware that the recent UN report on UNAMID’s failings—prompted by the shocking disclosures of reporting failures by former UNAMID spokeswoman Aicha Elbasri—is a whitewash, that finds no serious culpability in the reporting by UNAMID. And Ladsous is also aware that the whitewash was necessary to protect him and UN DPKO generally, since UNAMID is a “hybrid” UN and AU effort, with personnel wearing the symbolic UN blue helmets and all vehicles and aircraft marked “UN.”

The senior UN official who told me years ago that the UN would not feel safe conducting further studies of mortality in Darfur has certainly been vindicated by the performance of UNAMID, which cannot protect itself, let alone the people of Darfur who live in an environment of terrifying insecurity—or even report honestly, as the recent account of the Tabit rapes reveals. The UNAMID press release [November 10] declares, evidently without shame or hesitation:

None of those interviewed confirmed that any incident of rape took place in Tabit on the day of that media report. The team neither found any evidence nor received any information regarding the media allegations during the period in question. [Incredibly, no mention is made in the press release of the extraordinarily heavy military and security presence during the UNAMID investigation, or the obvious intimidation that had preceded the investigators’ arrival a week after they first sought entry—or the fact that this was ample time in which to sanitize the crime scene and ensure that all necessary intimidation had occurred—ER]

But why is UNAMID allowed to continue in its present disastrous ways? Here the answer lies in New York, not el-Fasher. UN DPKO simply refuses to speak honestly about the failings of the mission, its immensely consequential lack of reporting, and its refusal to intervene to protect civilians—and the vanishingly small likelihood that things will improve. The solution offered by Ladsous in late April 2012 was to declare that UNAMID could be drawn down because security in Darfur had improved; he made this claim even as violence was sharply escalating, and has continued to do so. His was apparently a desperately expedient and disingenuous attempt to reduce the cost of UNAMID to UN DPKO, tacit recognition of the mission’s failing. His assessment of “conditions on the ground” (Ladsous’ phrase) could not possibly have been so ill-informed. A year later Ladsous again simply lied again, declaring that UNAMID “has the inherent robustness to deal with the situation” in Darfur” (Agence France-Presse [Khartoum], July 2013). Everything we knew then and now about UNAMID contradicts this claim, and yet because it is made by the head of UN Peacekeeping Operations it stands unchallenged in the Security Council and the Secretariat. This is appalling deception and makes real improvement in the security conditions in Darfur impossible.

If UNAMID won’t report or speak honestly, if UN DPKO is more interested in reducing costs and deflecting blame, where does that leave us in addressing the question of mortality in Darfur? Given the gross and mutually self-serving expediency of UNAMID and UN DPKO, it is unlikely that the world will see any time soon—if ever—the counting of the hundreds of thousands of Darfuris “dishonored” in their deaths.

Images of Darfur’s future

APPENDIX ONE: 50,000 and not counting: South Sudan’s war dead

(Agence France-Presse [Nairobi] 15 November 2014)

When gunfire shattered the silence of a December evening last year in South Sudan’s capital Juba, initial reports pointed to several dozen rival soldiers dead. In the following days, gunfire and explosions continued to shake the city, as troops loyal to President Salva Kiir fought it out with those allied to his ousted deputy, Riek Machar, and terrified residents cowered in their homes and independent observers kept indoors under curfew. Witnesses reported soldiers going door-to-door, as members of Kiir’s Dinka tribe hunted down ethnic Nuer, the people of Machar. At night, bodies were discreetly trucked out of the city and burned or buried, witnesses and human rights groups say.

“We estimate as many as 5,000 people died in Juba during that first week alone. After that, it’s been the same kind of thing over and over again in other towns. In some places, people have been there to count, in others, not at all,” said one Western aid worker, who asked that his name nor that of his organization be published due to the sensitivity of the issue.

Eleven months on and South Sudan is still locked in civil war, with the killings in Juba having set off a cycle of retaliatory killings across large swathes of the country. Both Kiir’s forces and rebels loyal to Machar have been accused of widespread atrocities — massacres, gang rapes and child soldier recruitment—that have seen the country teeter on the brink of genocide. But missing from the conflict is a clear death toll, as nobody—not even United Nations peacekeepers—has been keeping count.

The International Crisis Group (ICG), a conflict think-tank, estimates at least 50,000 people have already died but it admits the true figure could even be double that. It also says the failure to count the dead is a scandal — both as a dishonour to the victims and as something that has kept the country’s suffering off the international radar.

“It’s shocking that in 2014, in a country with one of the largest UN peacekeeping missions in the world, tens of thousands of people can be killed and no one can even begin to confirm the death toll,” ICG researcher Casie Copeland told AFP. “Surely more can be done to understand whether the figure is closer to 50,000 or 1,00,000?” Instead, she argues, the South Sudanese are victims of a process of “appalling dehumanization”—the result being a lack of “concerted action to end the war.”

“Counting the dead goes beyond understanding the scale of this devastating war, it honours those who have been lost and is a minimum form of respect to the tens of thousands of South Sudanese who have been killed.” Akshaya Kumar of the Enough Project, a genocide prevention campaign group, stressed the need to create accountability with clear numbers in order to “counter the widespread belief that combatants have immunity in South Sudan.” “It’s an imperfect science but in other countries, such as Syria, the UN has done a much better job of tracking the numbers of civilians killed than in South Sudan,” added Skye Wheeler from Human Rights Watch.

“Alongside more vigorous reporting on human rights abuses, public estimates would have shed light on the violence and the extent of abuse, and helped put pressure on both sides to end abusive tactics.” The reality in South Sudan, however, has been the polar opposite: without any apparent fear of the consequences, armed groups have shot and gang raped patients in their hospital beds, massacred civilians in churches, machine-gunned fleeing civilians in swamps — leaving their bodies to rot, be carried away by the Nile river or be consumed by its crocodiles.

Tens of thousands more are feared to have died from hunger and disease in isolated villages, swamps and bush beyond the reach of aid agencies. The UN peacekeeping mission to South Sudan, UNMISS, says they are unable to provide “a reasonably precise estimate of the casualty toll”, saying only that “thousands” have been killed. The 14,000-strong peacekeeping mission said in a statement that it “doesn’t have a presence in every single county in South Sudan, so it is impossible to provide a comprehensive and independently verifiable number.”

The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs also admits it has “unfortunately … not been collecting information on the number of deaths since the crisis broke out” — although it does track those still alive, notably the 3.8 million people in need of aid and the 1.91 million people displaced. “If the UN is able to estimate with such precision the number of displaced, it is inexplicable that they cannot similarly monitor those killed,” the ICG’s Copeland said.

As the body counters opt out of South Sudan’s civil war, a group of South Sudanese civil society activists are trying to step in — launching the “Naming Those We Lost” project to try and name the dead. But they have a long way to go — having so far confirmed around a thousand names. “It’s a vital step to recognizing the collective loss,” said project organizer Anyieth D’Awol. “The lack of justice, accountability and acknowledgement of losses suffered by people has fuelled the current conflict.”

APPENDIX TWO:

A response to the findings of CRED researchers Olivier Degomme and Debarati Guha-Sapir, “Patterns of mortality rates in Darfur conflict,” The Lancet, January 23, 2010 (pages 294-300, http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2809%2961967-X/abstract

From: QUANTIFYING GENOCIDE: Darfur Mortality Update, 6 August 2010 | http://sudanreeves.org/2010/08/07/quantifying-genocide-darfur-mortality-update-august-6-2010/

Very usefully, many of…smaller-scale mortality reports have been extracted, collected, and analyzed by Olivier Degomme and Debarati Guha-Sapir… Their account draws in particular on the “Complex Emergency Database” (http://www.cedat.be/guidelines) of the Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED). While excluding from its estimates of violent mortality any consideration of the [Coalition for International Justice study commissioned by the US State Department, August – September 2004] their study offers important conclusions about deaths from disease and malnutrition that are likely to be approximately right, though excluding mortality in eastern Chad as well as mortality from the period February 2003 to “early 2004″ (see below for discussion of this critical lacuna).

This highly technical paper, statistically of enormous potential richness, offers some very clear conclusions: the authors “estimate the excess number of deaths in Darfur to be 298,271 (95% Confidence Interval, 178,258 – 461,520 [i.e., the high-end mortality figure that must be included to achieve their 95% confidence interval—ER, 16 November 2014] in the time period “from early 2004 to the end of 2008″ (N.B. the terminus a quo and the terminus ad quem). Of these approximately 300,000 excess deaths, they argue that “more than 80% of the excess deaths were not as a result of the violence” but from “diseases such as diarrhoea,” at least on the basis of the numerous studies archived at CRED’s “Complex Emergency Database.” This yields a figure of roughly 240,000 deaths from disease (which presumably includes the effects of malnutrition, which has in various times and places in Darfur been extremely high), and a corresponding figure of roughly 60,000 deaths from violence in the period “from early 2004 to the end of 2008.”

Unfortunately, Degomme and Guha-Sapir seem incapable of recognizing the direct connection between deaths from disease and malnutrition and the antecedent violence that was responsible for these deaths—this is so even as they speak abstractly of “excess deaths.” Indeed, they seem to have only a very superficial knowledge of Darfur and the nature of the conflict, as well as key date markers. But of course the deaths they speak of are “excessive” because of the genocidal violence that created the conditions in which people died of malnutrition and disease. And there is nothing abstract about this brutal violence. For the moment, however, we may ignore this peculiar myopia.

In the course of their study, the authors explain their limitations. They have not included mortality in Chad (again, 57,250 people killed according to data from “Darfurian Voices,” in addition to victims of disease and malnutrition). They have not included mortality from December 2008 to the present. But even more tellingly they confess that, “Another constraint was that we could not identify any survey that included the first few months of the conflict before the deterioration in September, 2003.” [Their suggestion that the conflict “deteriorated” in September 2003 seriously misrepresents the escalation of violence following the successful raid on el-Fasher air base in April 2003, the precipitating event in launching the Janjaweed militia forces in a campaign of wholesale civilian destruction, targeting non-Arab or African villages—ER, 16 November 2014]

In fact, there are no mortality studies at all for Darfur for the year 2003 in CRED’s “Complex Emergency Database”: entering this year and any of the three Darfur states into the site’s search engine yields only the message, “No entries found, please try broaden your search parameters.” This is why Degomme and Guha-Sapir’s narrative indicates that the period actually represented by their conclusions is January or February 2004 to December 2008, not February 2003, when conflict actually begins in earnest: “298,271 (95% Confidence Interval, 178,258 – 461,520)” excess deaths in the time period “from early 2004 to the end of 2008.” (Tellingly, the authors do not specify precisely what is meant by “early 2004.”)

This delimitation of time period is highly significant. In excluding the period from February 2003 to “early 2004″—an approximately yearlong period of extraordinary violent mortality, as well as highly significant mortality from other causes—the authors leave out an essential part of the global mortality picture with almost no acknowledgement. Of the half-year period from February 2003 to August 2003 (“phase 1″ in their Panel 1) they say only: “not included in any retrospective survey, and mortality data should therefore be estimated by other techniques.”

The truth is that they have not identified any Darfur mortality study for any months in 2003. Even so, Degomme and Guha-Sapir push on to offer what is a transparently untenable figure from the US State Department for this critically omitted period of time (“February [2003] to August 2003″): “between 1,000 4,500 deaths” (from all causes).

In fact, this figure is an erroneous citation by the authors: the State Department “fact sheet” (“Sudan: Death Toll in Darfur,” March 25, 2005)—as originally promulgated on the State Department website—found that “4,100 – 8,800 excess deaths are estimated to have occurred primarily in North and West Darfur [during the period March September 2003].” Notably, though unsurprisingly, Degomme and Guha-Sapir do not cite the URL for this State Department estimate; rather they cite the tendentious U.S. Government Accounting Office report on mortality studies that cites this four-page “fact sheet.” The inability to cite the URL for the document in question derives from the fact that the State Department removed this statistical travesty from its website (www.state.gov/s/inr/rls/fs/2005/45105.htm is now a dead link). But at the time of its initial distribution I analyzed in detail (http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article9364) the “fact sheet’s” numerous methodological problems, its highly consequential factual errors, the lack of citation or statistical analysis, and a consistent disingenuousness (I accessed the document from the State Department website on April 23, 2005 at the now defunct URL).

Critically for present purposes, Degomme and Guha-Sapir leave ambiguous whether there are relevant mortality studies or considerations for the period between September 2003 and January 2004, this despite their subsequent parceling out of various “phases of the Darfur conflict,” including “September 2003 to March 2004″ (“phase 2″ of Panel 1—again, N.B. the terminus ad quem for this “phase”). In their statistical analysis for this period they indicate “excess deaths” of “45,137 (95% Confidence Interval, 27,320 to 73,380).” But it remains unclear what data were used for September 2003 through the end of December 2003: again, there is nothing in CRED’s “Complex Emergency Database.” Nor is it clear what data was used to calculate violent mortality for the period January 2004 to their “March 2004″ endpoint for “phase 2…”

Let us be clear about the significance of the figure “1,000 4,500″ deaths—from all causes—in the period February 2003 through August 2003 (by which time Khartoum had substantially deployed its Janjaweed militias, as well as its regular military forces, in genocidal destruction). It is simply preposterous and has no justification in fact or data. Degomme and Guha-Sapir conclude that total excess mortality in Darfur is 298,271 “from early 2004 to the end of 2008.” But by a tawdry statistical sleight-of-hand, this time-frame is disingenuously expanded by almost a year to become “about 300,00″ “between March 2003 and December 2008.” A year that includes some of the greatest violent mortality in the Darfur genocide (February 2003 to “early 2004″) is brought within their final estimate and time-frame on the basis of a completely vitiated State Department “fact sheet,” which purportedly supports an estimate of “between 1,000 – 4,500 deaths” in this time period.