Khartoum’s Military Offensive in the Nuba Mountains: Chemical weapons use is imminent according to highly reliable source

Eric Reeves | 14 November 2014 | http://wp.me/p45rOG-1×6

[This previous overview should be read in light of the September 29, 2016 report by Amnesty International on Khartoum’s campaign against civilians in Jebel Marra

“Scorched Earth, Poisoned Air: Sudanese Government Forces Ravage Jebel Marra, Darfur,” Amnesty International (109 pages; released September 29, 2016)]

Serious fighting has begun in the Dalami area of South Kordofan, where Khartoum’s Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) are determined to end the war militarily this year. It has been almost three and a half years since Khartoum initiated fighting on June 5, 2011, and the regime—and the army leadership in particular—is well aware that this conflict, along with those in Blue Nile and Darfur, is bleeding the meager, and declining, revenues that remain available amidst an imploding economy. The situation might well be described as desperate from Khartoum’s point of view, something that emerges clearly in the leaked minutes of the August 31 meeting of senior military and security officials in Khartoum [see Arabic original and English translation at http://wp.me/p45rOG-1tC/].

Because there is a promising crop of sorghum this year in South Kordofan (the grain staple in the Nuba Mountains, where fighting is now concentrated), the regime has decided to destroy the crop as a means of “starving” the civilians who are perceived as the base of support for the rebels. The words of Lt. General Siddiig Aamir, Director of Military Intelligence and Security, were blunt:

“This year the Sudan People’s Army (SPLA-N) managed to cultivate large areas in South Kordofan State. We must not allow them to harvest these crops. We should prevent them. Good harvest means supplies to the war effort. We must starve them, so that, commanders and civilians desert them and we recruit the deserters to use them in the war to defeat the rebels.”

He is echoed by Lt. General Imadadiin Adaw, Chief of Joint Operations: “We should attack them before the harvest and bombard their food stores and block them completely.”

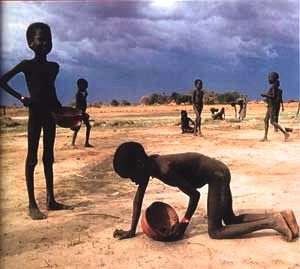

This is what “starving” people look like—mother and child

This is what “starving” people look like—children hunting for ants during the terrible famine in Bahr el-Ghazal (1998)

Such genocidal barbarism—conducting war by means of starving civilians of a particular ethnicity—should make all too plausible the report that has very recently come to me from a highly reliable source in the Nuba: during the Dalami offensive, Khartoum plans to use chemical weapons to secure control of this key town. My source from the Nuba reports that “residents of Dalami Locality have started fleeing into caves due to fear of the shelling and fears of a potential chemical attack.”

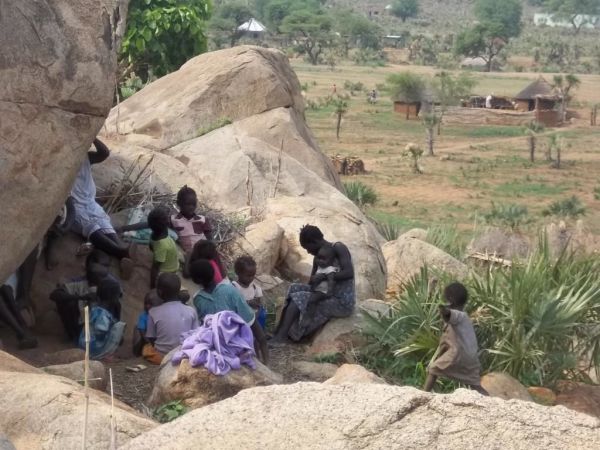

For more than three years now, people have been forced to flee their lands and villages because of relentless aerial assault; their grim lives are lived in caves.

There have been numerous reports over many years of the Khartoum regime’s possession and use of chemical weapons. The misguided U.S. intelligence that led to the mistaken attack on the al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory should do nothing to blind us to the evidence and reports we do have. Perhaps the most compelling of these reports came from Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in their 2000 study of Khartoum’s relentless bombing of civilian and humanitarian targets (it is worth recalling that MSF won the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize):

MSF [Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders] is particularly worried about the use or alleged use of prohibited weapons (such as cluster bombs and chemical bombs) that have indiscriminate effect. The allegations regarding the use of chemical bombs started on 23 July 1999, when the villages of Lainya and Loka (Yei County) were bombed with chemical products. In a reaction to this event, a group of non-governmental organizations had taken samples on the 30th of July, and on the 7th of August; the United Nations did the same.

Although the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) is competent and empowered to carry out such an “investigation of alleged use,” it needs an official request made by another State Party. To date, we deplore that OPCW has not received any official request from any State Party to investigate, and that since the UN sample-taking, no public statement has been made concerning these samples or the results of the laboratory tests.

MSF offers several eyewitness accounts of chemical weapons in bombs, including a grim narrative of events in Yei County (now Central Equatoria):

The increase of the bombings on the civilian population and civilian targets in 1999 was accompanied by the use of cluster bombs and weapons containing chemical products. On 23 July 1999, the towns of Lainya and Loka (Yei County) were bombed with chemical products. At the time of this bombing, the usual subsequent results (i.e., shrapnel, destruction to the immediate environment, impact, etc.) did not take place. [Rather], the aftermath of this bombing resulted in a nauseating, thick cloud of smoke, and later symptoms such as children and adults vomiting blood and pregnant women having miscarriages were reported.

These symptoms of the victims leave no doubt as to the nature of the weapons used. Two field staff of the World Food Program (WFP) who went back to Lainya, three days after the bombing, had to be evacuated on the 27th of July. They were suffering from nausea, vomiting, eye and skin burns, loss of balance and headaches.

After this incident, the WFP interrupted its operations in the area, and most of the humanitarian organizations that are members of the Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) had to suspend their activities after the UN had declared the area to be dangerous for its personnel.

MSF concludes:

[E]vidence has been found and serious allegations have been made that weapons of internationally prohibited nature are regularly employed against the civilian population, such as cluster bombs and bombs with “chemical contents.” (Living under aerial bombardments: Report of an investigation in the Province of Equatoria, Southern Sudan, February 20, 2000)

The cluster bombs MSF reports have in fact been used in a number of locations, including the against civilians and the rebel Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North. Below is a photograph of what such ordnance looks like if it fails to detonate (each of the bomblets may carry ball bearings, flechettes, or other weapons designed to kill or main “soft targets”). There are may be thousands in a single bomb.

An unexploded cluster bomb (anti-personnel bomb) dropped in South Kordofan

A piece of shrapnel from an Antonov barrel-bomb; it can easily cut right through a person

A young victim of an Antonov attack

Chemical weapons delivered by aerial bombardment have also been repeatedly reported by Darfuris, over a number of years, especially in the Jebel Marra area. Khartoum continues to deny the UN/African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) access to Jebel Marra, in blatant contravention of the Status of Forces Agreement (2008). Even so, in 2004 the German newspaper Die Welt reported (15 September 2004) that Syria tested chemical weapons on civilians in Sudan’s Darfur region in June and killed dozens of people. Die Welt cited unnamed western security sources, saying that injuries apparently caused by chemical arms were found on the bodies of the victims.

[The article in Die Welt] said that witnesses quoted by an Arabic news website called ILAF in an article on August 2 had said that several frozen bodies arrived suddenly at the “al-Fasher Hospital” in Khartoum in June. Die Welt’s sources had indicated that the weapons tests were undertaken following a military exercise between Syria and Sudan. Syrian officers were reported to have met in May with Sudanese military leaders in a Khartoum suburb to discuss the possibility of improving cooperation between their armies. According to Die Welt, the Syrians had suggested close cooperation on developing chemical weapons, and it was proposed that the arms be tested on the rebel SPLA, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, in the south. (summary by Agence France-Press, 16 September 2004)

Many of Khartoum’s weapons come from Iran, part of the “strategic relationship” that is so often evoked in the minutes of August 31, indeed celebrated by Defense Minister Lt. Gen. Abdal-Rahim Mohammed Hussein:

I start with our relation with Iran and say it is strategic and everlasting. We cannot compromise or lose it. All the advancement in our military industry is from Iran. They opened the doors of their stores of weapons for us, at a time the Arabs stood against us. The Iranian support came at a time we were fighting a rebellion that spread in all the directions including the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). The Iranian provided us with experts and they trained our M.I. and security cadres. Also they trained us in weapons production and transferred to us modern technology in military production industry.

They are still present with us. There is one full Battalion of the Republican Guards still with us here and other experts who are constructing for us interception and spying bases in order to protect us, plus an advanced Air Defense system. They built for us Kenana and Jebel Awliya Air Force bases. One month ago they transported to us BM missile launchers and their rockets using civil aviation planes.

Iran’s chemical weapons capacity is unclear at present, but they have certainly manufactured such weapons in the past, notably in the wake of the war with Iraq, in which Saddam Hussein ordered the use of chemical weapons to turn back an Iranian assault. There have been several reports that Saddam off-loaded much of his chemical weaponry to Sudan prior to the first Gulf War. Iran and Sudan are both signatories to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons, but this clearly means little. Moreover, the regime certainly has the capacity, in the military industrial complexes outside Khartoum, to manufacture simpler chemical weapons (e.g., mustard gas) and perhaps even more toxic and militarily sophisticated agents.

[ On 23 October 2012 Israel launched a midnight raid on the Yarmouk arms factory outside Khartoum. The attack started a huge fire in the factory and surrounding buildings. Though unconfirmed by Israel itself, the attack almost certain took place as described and with the purpose of destroying what was believed to by Khartoum’s chemical weapons capacity. Sudan has long been a conduit for Iranian weapons making their way to Hamas in Gaza. ]

At the very least, the international community should be closely monitoring fighting in the Dalami area of South Kordofan, and should attempt to gather as much information as possible from the ground.

Indiscriminate Aerial Warfare

The primary reason for an international convention banning chemical weapons is their inherently indiscriminate nature: they are as likely to kill a child or a pregnant woman as an enemy soldier. Slight shifts in wind direction can wreak havoc with any efforts at “targeting,” a futile endeavor in any event.

But if Khartoum has demonstrated anything over the years in fighting South Sudan, in Darfur, in South Kordofan and Blue Nile, it is that the regime cares nothing about the indiscriminate use of its weaponry. Antonov “bombers”—which recently attacked South Sudan near Raga in Western Bahr el-Ghazal and Upper Nile some 30 miles northeast of Bunj (Kortombak, Mabaan County)—are the mainstay of Khartoum’s aerial war-making and are by their very nature indiscriminate. They are not military aircraft at all, but retrofitted Russian cargo planes; they fly at very high altitudes (from a military point of view) to avoid ground fire, even as this reduces their accuracy tremendously. And this “accuracy” is very poor to begin with: there is no bomb-sighting equipment, and bombs are simply rolled out the cargo bay. They are loaded with shrapnel, and while modest in explosive force, that force is more than enough to send deadly shrapnel in all directions.

Antonov “bomber” (crudely retro-fitted Russian cargo plane)

When I traveled in South Sudan in early 2003, before the cease-fire of October 2002 had fully taken hold, there were fox-hole bomb shelters at every civilian site I saw.

A foxhole dug for protection from Antonov “bombers” (Yei Market)

The market at Yei in Central Equatoria, for example, was lively and filled with food and various items. But near virtually every stall was a fox-hole of the sort that appears below. Yei market was directly hit with Antonov shrapnel bombs in 2000, killing many and wounding many more. Reuters reported at the time:

“Our agents said the bombs fell at 2:45pm (1145 GMT),” said Dan Eiffe, a spokesman for the Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) group which has operations in south Sudan. “We heard the news by radio. Apparently the bombs landed smack in the middle of a market place. It is carnage,” he added. (Reuters [Nairobi] 20 November 2000)

Sudan has also used in South Kordofan a highly significant new aerial weapon, Chinese long-range missiles. On February 17 and 18, 2012, advanced, long-range Chinese WeiShi rockets hit the villages of Um Serdeba and Tabanya in the Nuba Mountains (an earlier attack was reported by Ryan Boyette from the Nuba Mountains to Sudan Tribune, 5 December 2011). A father was killed in these later attacks, along with his three daughters and a son; his wife and another child were badly wounded. Enough fragments survived from these attacks to be identified by a weapons expert working for Amnesty International:

The [WeiShi] rockets fired from more than 25 miles away, travel at 3,000 miles per hour and pack a 330-pound warhead often loaded with steel ball bearings to increase lethality, experts say. Where they land is random, witnesses say, and they often slam into villages instead of legitimate military targets. “They arrive without any warning,” said Helen Hughes, an arms control researcher at Amnesty International. “And they are being used indiscriminately, which is violation of international humanitarian law.” (New York Times [Nairobi], March 13, 2012)

Amnesty International also reported WeiShi missile attacks in June 2012:

China has also been one of the main suppliers of conventional arms to the SAF. Amnesty International has identified the use of Chinese-manufactured 302mm Weishi multiple-launch rockets in ground bombardments in the area of Kauda in late 2011 and early 2012, which have been used indiscriminately in civilian areas. (“‘We can run away from bombs, but not from hunger’: Sudan’s Refugees in South Sudan,” June 2012, page 11)

It is impossible to credit Khartoum with any moral scruples about whether or not to use chemical weapons, given the indiscriminate nature of the weapons favored: Antonov bombings; cluster bombs; long-range missiles that cannot be targeted accurately. And given Khartoum’s “strategic relationship with Iran”, there can be little doubt that chemical weapons are available to the regime, and again, the secretive military production plants outside Khartoum may also be producing chemical weapons.

Given the military frustration with the determined resistance put up in South Kordofan by the forces of Abdel Aziz al-Hilu and the SPLA-North, there is undoubtedly a powerful temptation to use chemical weapons against an enemy they cannot defeat in any other way.

If Khartoum feels the eyes of the world are not on its military actions in the Dalami region, the regime will be that much closer to using chemical weapons against its foes—and inevitably any civilians who are caught up in the clouds of chemical weapons.