Eric Reeves, 15 July 2014 •

These twelve news reports and press releases below, long and short, all point to the same present realities: food insecurity already—right now—threatens some 4 million people in South Sudan; famine is “inevitable” in the words of a senior official of the US Agency for International Development; children are dying of malnutrition at ghastly rates well in excess of the emergency threshold in some locations; there was very little planting done during the appropriate months of spring to late spring, and an equally paltry harvest may be expected in the fall; armed looting of humanitarian supplies has become an acute problem.

Terrifying numbers of South Sudanese are fleeing to neighboring countries, particularly Ethiopia—perhaps as many as 700,000 by the end of the year the UN High Commission for Refugees has recently indicated. And inevitably this creates humanitarian crises in their own right. Despite these extraordinary realities and threats—judged as extraordinary even by some of the most experienced relief workers in the world—there are painfully large budget gaps in funding the bare minimum necessary for human survival in South Sudan. Neither UN agencies nor international nongovernmental relief organizations (INGOs) have nearly the funding they require. In the global allocation of money for all development and assistance efforts, South Sudan is suffering a morally intolerable deficit. There is no more urgent need for humanitarian efforts. What is unfolding in South Sudan—at this very moment—is the beginning of what may be one of the largest and most destructive famines in the past half century.

How to help

I know well and modestly support the work of many organizations operating in South Sudan through my Sudan Aid Fund (http://wp.me/p45rOG-V7/). All these organizations devote approximately 87 – 90 percent of funds raised to programs in the field; all have the highest rating awarded by Charity Navigator.

Another means of supporting this work, and acquiring a woodturning as well: see

https://www.etsy.com/shop/EricReevesWoodturner

These in particular have compelled my own giving:

• International Rescue Committee | http://www.rescue.org/

• Oxfam America | http://www.oxfamamerica.org/

• Save the Children | http://www.savethechildren.org/site/c.8rKLIXMGIpI4E/b.6115947/k.8D6E/Official_Site.htm

• Action Contre la Faim/Action Against Hunger | http://www.actionagainsthunger.org/

• Médecins Sans Frontières | http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/

• Catholic Relief Services | http://crs.org/

• Mercy Corps | http://www.mercycorps.org/south-sudan

Critical work is also being done by:

•International Committee of the Red Cross | http://www.icrc.org/eng/

•Samaritan’s Purse | http://www.samaritanspurse.org/?s=sudan

•Medair | http://relief.medair.org/en/where-we-help/south-sudan/

…and a number of other organizations are performing heroically, under extremely difficult—and often dangerous—circumstances, but face crippling funding deficits. All have particularly highlighted the vast humanitarian crisis in South Sudan.

UN organizations are also critically short of funding, especially:

• UNICEF (the UN’s Children Emergency Fund)

• UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR)

• UN World Food Program (WFP)

In the end, it is essentially up to wealthier donor nations to commit to UN and well as nongovernmental efforts. Commitments to help the people of South Sudan can be influenced by sufficient political pressure.

At the same time, intense political and diplomatic pressure must be brought to bear on the warring parties that have precipitated this massive crisis in South Sudan and bordering countries. A cease-fire, a genuine willingness by all political actors to discuss and implement governance reform, and a strong commitment to protect human rights are the context for any permanent protection of civilian lives and livelihoods in this young nation.

Twelve recent news reports, press releases from the past month

[1] PRESS RELEASE, FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) – JULY 14, 2014

CHILD MALNUTRITION RATES SKYROCKET IN SOUTH SUDAN

Children in parts of South Sudan are suffering from shocking rates of malnutrition, the international medical humanitarian organization Doctors Without Borders/ Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) said today.More than 13,270 children, most under the age of five, have been admitted to MSF feeding programs in South Sudan so far this year, amounting to 73 percent of the 18,125 admissions during the whole of 2013. Violence, displacement, and food shortages are the leading causes of the spike in malnutrition rates and the increasing numbers of children requiring urgent medical care in some locations where MSF is working. “We are now witnessing the shocking, cumulative consequences of one million people being displaced from their homes,” said Raphael Gorgeu, MSF head of mission in South Sudan. “This is a man-made disaster. Some people have been living in the bush for six months, drinking dirty swamp water and eating roots to survive.”

Rates of malnutrition have skyrocketed in parts of Upper Nile, Unity and Jonglei States since conflict erupted in South Sudan in December. In the town of Leer in Unity State, MSF teams were treating 40 malnutrition cases each month before the outbreak of hostilities. More than 1,000 new cases per month are now being treated. In Unity State, the scale of the malnutrition became clear when people who had been displaced by fighting returned to the town of Leer in May, following months living in the bush. “They began streaming into the hospital,” said Sarah Maynard, MSF project coordinator in Leer. “It was overwhelming. The levels of malnutrition were startling.”

MSF has admitted more people for malnutrition in Leer during just the last two months (2,810 cases in May and June 2014) than in all of 2013 (2,142 malnutrition cases). In Bentiu, a specialized MSF facility set up in May 2014 to treat severely malnourished people suffering from medical complications, including diarrhea, chest infections and dehydration, has already admitted 239 children, of whom 42 have died. In Jonglei state, MSF facilities in Lankien and Yuai have seen a 60 percent increase in admissions in the first six months of the year compared to the same period last year, from an average of 175 per month in 2013 to 290 admissions per month in 2014 so far. In Upper Nile State, MSF teams have admitted 2,064 people, mostly children, in the area north of Malakal. A recent mortality survey carried out there revealed very high death rates.

“Displaced people are forced to endure terrible living conditions and are dying from preventable illnesses,” said Patricia Trigales, MSF emergency medical coordinator. In Nasir, fighting in May forced MSF teams to evacuate its projects and many people fled the town, crossing into neighboring Ethiopia. MSF teams providing primary health care to hundreds of refugees crossing the border every day into the Gambella region report newly arriving malnourished refugees and high malnutrition rates overall: 20 percent for global acute malnutrition and 6 percent for severe acute malnutrition, which are well above emergency threshold levels. Testimonies from refugees describe food and safe shelter as important motivators for coming to Gambella.

“In May, South Sudanese fled because of the fighting,” said Dr. Natalie Roberts, MSF medical coordinator in Gambella. “Now they say they have left their country because of food deprivation.”

The vast numbers of displaced people in the bush have lost their cattle, crops, seeds and farming implements. They are trying to survive on a diet of roots and leaves, while living amidst muddy swamp water. The violence has interrupted planting and has prevented crop harvesting. Existing food stocks have been destroyed or looted. Markets have been disrupted and roads are impassable due to the conflict. The ongoing rainy season and annual “lean season” (usually from June to August, when food is scarce) are exacerbating the food crisis.

“Many people are now entirely dependent on humanitarian assistance to survive and will be for the foreseeable future,” said Gorgeu. “Continued humanitarian assistance in South Sudan is absolutely crucial to alleviate some of the suffering this conflict has caused.” Humanitarian actors on the ground must scale up assistance, preposition adequate supplies regionally to ensure food distributions, and meet funding goals to ensure people receive the assistance they deserve. Parties to the conflict must ensure that everything is done to facilitate humanitarian assistance to populations in need. This includes securing safe access by road and river within South Sudan as well as cross-border corridors for the delivery of humanitarian aid.

One of many young victims of cholera

[2] Via Twitter: UNOCHA South Sudan @OCHASouthSudan July 15 #SouthSudan #Cholera update – as of 13 July, there are 3403 total cholera cases, with 80 cumulative deaths (case fatality 2.4%) ht @WHO

[3] “Famine ‘Almost a Certainty,'” Africa Confidential, July 11, 2014, Vol. 55, No. 14 | http://www.africa-confidential.com/article-preview/id/5686/Famine_%E2%80%98almost_a_certainty%E2%80%99

The conflict has caused a food emergency and sanctions against the rival leaders for blocking progress are now on the table. One million South Sudanese are threatened by starvation, with at least another three million at serious risk, United Nations and United States’ officials say. The US Agency for International Development’s Assistant Administrator for Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance, Nancy Lindborg, gave the warning after the annual board meeting of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in Brussels on 2 July.

USAID’s “complex emergency” map shows the whole country except Western Equatoria as at least “stressed” for food security and most of it at “crisis” or “emergency” level. The next category is “catastrophe/ famine” and that is likely to be declared next month. “It is almost a certainty,” Lindborg told Africa Confidential. Nearly 100,000 people who have taken refuge from the violence in ten ever-expanding compounds of the UN Mission in South Sudan are at risk of cholera and other diseases. Another 100,000 at least, mainly women and children, are in Ethiopia’s Gambella Region, where the impact on local Nuer-Anyuak politics is worrying Premier Hailemariam Desalegn’s government, we understand.

Even more at risk are people, often displaced, in the three main conflict states: Unity, Upper Nile and Jonglei. These are hard to reach, even in peacetime, during the rainy season which is now under way. Vast areas are flooded, and the unmetalled roads are impassable. People haven’t been able to plant and food markets are disrupted. The only way to get assistance in right now is by air or by barge, said Lindborg. There is an urgent need for more money. OCHA says US$1.8 billion is needed to avert the loss of yet another generation of children but donors have so far committed only 40.3% or $725.4 million. Crises in Central African Republic, Iraq and Syria are also placing heavy demands on donor funds and staff – and summer is a bad time to appeal to the public in rich countries.

Aid agencies are concerned that they may not raise enough to cover the cost of a campaign. These problems might have been avoided if the UN and other donors had acted earlier to get food stocks in, say some aid workers. “It might not have worked,” said one in South Sudan, “but it is disturbing that we never made the attempt.” Part of the reason for this is donor politics but local politics is a bigger one.

[4] “Rainy season worsens South Sudan crisis; at one UN site alone, approximately four children below the age of five are dying each day,” Simona Foltyn for al-Jazeera [Bentiu, South Sudan], 13 Jul 2014

The onset of the rainy season has further exacerbated the ongoing humanitarian crisis in South Sudan. The UN warns that up to four million people are at risk of food insecurity, with young children facing the highest risk of malnutrition. One-year-old Chieng has been battling for his life for weeks. His father Peter sits by his side, fending off the relentless assault of flies.

Chieng suffers from acute diarrhoea, suspected TB and is fighting respiratory failure. His ribs protrude visibly through his thin skin as his chest rapidly pumps air into his tiny body. Chieng is one of 58 children admitted to Doctors without Borders (MSF) intensive therapeutic feeding centre in Bentiu’s UN Protection of Civilians (POC) site. Peter expresses hope that Chieng is getting better and says this clinic is his only chance for survival. As he speaks, a thunderstorm erupts, putting an end to a week-long dry spell unusual for this time of the year. Within minutes, the camp gets submerged in mud and water.

Some of the medical staff fear that the latest downpour will bring a new wave of admissions – and deaths. “The children are already malnourished and have very little fat to keep them warm. When it rains, they easily develop a cough or catch pneumonia, which makes their condition very serious,” Helmi Emmen, a paediatric nurse at the MSF clinic, told Al Jazeera. The next morning she tells Al Jazeera that Chieng was one of three children who passed away overnight.

Child mortality in Bentiu’s POC site has reached alarming levels, with approximately four children below the age of five dying per day. Aid workers fight an uphill battle against the deplorable water and sanitation conditions in the camp, which provide fertile ground for diseases. “Repeating cycles of infections accompanied by a drop in appetite often result in children eventually developing malnutrition. They never quite get better before the next infection comes along,” Vanessa Cramond, MSF’s health adviser, explains.

Approximately 45,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) have sought refuge at the POC site near Bentiu. They constitute the largest share of over 100,000 people currently living in UN bases as a result of South Sudan’s most recent violent conflict. An additional million are displaced around the country, and unlikely to return home anytime soon given the lack of respect for the ceasefire by government and opposition forces. With the increasing likelihood of a protracted humanitarian crisis, the UN and NGOs are trying to cope with the overcrowded conditions in Bentiu camp. “We are trying our best to catch up with the needs but it ‘ s very difficult with the rainy season plus the insecurity outside,” says Nora Echaibi, medical team leader at MSF Bentiu.

As of mid-June, only four litres of clean water were supplied per day compared to the minimum international standard of 15 litres, forcing many people to draw water from contaminated water sources. Only one pit latrine is available per 241 people, resulting in substantial open defecation around the camp. Heavy rains and muddy soil pose additional logistical challenges for water and sanitation teams trying to expand and maintain critical infrastructure. With ongoing insecurity and fighting outside the UN base, the population has been largely reliant on food aid.

The WFP conducts biweekly food distributions, yet ensuring families get the right amount of nutritional intake has proven difficult given high fluctuations in population levels as well as frequent sharing with families within, as well as outside the camp. “We only eat once per day,” Mary Nyajak, a mother of 10 told Al Jazeera. Four of her children stay with her inside the camp, while six others hide in the bush attending to the family’s cattle. “Sometimes family members come here and we give them food which they take back,” Nyajak says. Sharing food with extended families often means that children, the weakest members of the family, fall short of their requirements. Aid agencies warn that the rainy season further compounds the humanitarian crisis which already affects almost a third of South Sudan’s population of 11.3 million. According to UN estimates, 3.5 million people suffer from food insecurity, a number expected to increase to 4 million by August.

Although famine has not yet been declared and most people fall into categories three (acute food insecurity) and four (humanitarian emergency) on the UN’s five scale integrated food security phase classification, the situation could quickly deteriorate. “We are very worried about this population of 3.5 million, particularly those in phase four, because additional shocks, such as the lack of access to humanitarian assistance or continued inability for traders to come in with commercial goods, means that the population is extremely vulnerable to further decline,” Sue Lautze, deputy humanitarian coordinator and head of FAO in South Sudan told Al Jazeera.

Diversions of aid from intended beneficiaries to other parts of the population, including armed groups, risk further diluting of relief efforts. Only a few kilometres away from the Bentiu POC site, USAID grains openly get sold in the Rubkona market. Many of the customers here are SPLA soldiers from Rubkona’s fourth division. Sue Lautze says aid diversions are difficult to trace. “We give the assistance to the right people, but ensuring they hang on to it is difficult. But we are currently investigating allegations of food diversion.” The past six months of conflict further exacerbates the effects on long-term food security. Massive displacements and ongoing fighting have prevented farmers from tending to their fields. Development programmes aimed at increasing farming productivity and livestock health have come to a grinding halt, thus laying the foundations for long-term dependency on humanitarian aid.

Funding and access constraints

Despite the growing needs, international donor support has fallen short of the requirements thus far. Only $756m have been received towards the $1.8bn consolidated humanitarian appeal to cover the ongoing emergency in 2014. A lack of funding has been further compounded by a 30 percent drop in oil production as a result of the conflict, prompting the government to cut much needed development funds in favour of other spending areas. “We are producing 175,000 barrels [of oil] per day, which is sufficient to pay for the salaries of those who work for the government, but in the area of development, the impact has been very bad,” Ateny Wek Ateny, the spokesperson of the Office of the President, told Al Jazeera.

Gaining access to vulnerable populations has been a challenge amid ongoing fighting. Some areas are off limits to aid agencies, while the situation along the front-lines complicates liaison with the relevant authorities to ensure smooth passage of aid. The proliferation of armaments within the population along with a rising number of often autonomous checkpoints implies that orders from the top do not always get respected on the ground.

WFP has recently confirmed instances of looting which tend to occur especially when areas change hands between the government and rebels. “More recently 4,600 metric tonnes were looted, which is enough to feed a population of 275,000 people per month,” Joyce Luma, WFP’s country director in South Sudan told Al Jazeera. With the indefinite adjournment of peace talks, and the lack of a mechanism to enforce the ceasefire, hostilities as well as the humanitarian crisis are unlikely to subside. ” The main problem is that they are fighting. The lack of respect for the cessation of hostilities agreements is the number one access constraint,” Lautze told Al Jazeera.

[5] “Ethiopia Facing Flood of South Sudan Refugees: UN,” Agence France-Presse [Geneva], 2 July 2014)

Ethiopia is facing a huge wave of refugees from South Sudan, where the spectre of famine threatens to heap further misery on a people already rocked by civil war, the UN’s food aid agency warned on Wednesday. “The numbers are increasing exponentially in a very short period of time,” said Abdou Dieng, head of the World Food Programme’s Ethiopia operations. There are already around 147,000 South Sudanese refugees in camps in neighbouring Ethiopia, and at least 1,500 more are crossing the border every week.

“The situation is not improving in South Sudan, so we expect that they will continue to come. If there is a famine in South Sudan, as many people think there will be, that will push more people to come into Ethiopia,” he told reporters. The UN forecasts the South Sudanese refugee numbers could spiral to 300,000 by the end of the year. All told there are around half a million refugees – largely women and children – in camps in the country. Apart from the South Sudanese, most are from Somalia, which huge numbers fled amid conflict and a 2011 drought, and Eritrea, where mounting numbers are escaping the iron grip of the country’s regime.

“The government has a policy that they call the ‘open-door policy’ for refugees. Ethiopia today is hosting one of the biggest refugee numbers, without talking too much about it,” said Dieng. The UN needs around $20 million (14.6 million euros) per month to help feed refugees in Ethiopia, but is facing a massive funding shortfall and fears that its coffers will be empty by October, he added. South Sudan only gained its independence from Sudan three years ago after decades of fighting, and has been ravaged by ethnically-tinged conflict between rebels and the government since December. The fighting has driven more than one million people from their homes, meaning that many farmers have missed the planting season.

[6] “Armed men have killed at least 58 people at hospitals in South Sudan in the last six months, often shooting patients in their beds, medical charity Médecins Sans Frontières said on Tuesday,” (BBC [London] 3 July 2014)

Hospitals in the world’s newest country have been ransacked or set ablaze in at least six attacks, leaving hundreds of thousands of people cut off from healthcare, MSF said. Ambulances, hospital equipment, medicines and beds have been destroyed or stolen. Attackers have also killed health ministry staff. “The conflict has at times seen horrific levels of violence,” said MSF head of mission Raphael Gorgeu. “Patients have been shot in their beds, and lifesaving medical facilities have been burned and destroyed. These attacks have far-reaching consequences for hundreds of thousands of people who are cut off from medical care.”

Details of the attacks are outlined in an MSF report which calls for greater measures to ensure safe access to healthcare in South Sudan, where ethnic-fuelled violence threatens to tear apart a nation that only gained independence from Sudan in 2011. MSF, which has over 3,600 staff running 22 projects in the country, said hospitals have been ransacked in the towns of Bor, Malakal, Bentiu, Nasir and Leer. Probably the worst affected is Leer Hospital in Unity state which was destroyed early this year, along with equipment for surgery, the storage of vaccines and blood transfusions. It was the only secondary healthcare facility for approximately 270,000 people.

“Unfortunately, because of this crisis we lost track of many of our patients, some of whom may have died if they could not access ongoing treatment,” said MSF medical coordinator Muhammed Shoaib. “Now, we are back and treating some patients, but can only offer a fraction of our previous services. There are no options at all for surgery in the whole of southern Unity state, for example.” In February, armed groups shot dead 11 patients in their beds at Malakal Teaching Hospital in Upper Nile state. Survivors of the carnage told how gunmen shot patients who had no money or mobile phones to hand over. The attack came after 14 patients were shot dead at Bor State Hospital in Jonglei state in December. In April, attackers killed at least 27 people at Bentiu State Hospital who had sought shelter there after fleeing fighting. MSF said its figures only represented what it knew about incidents in areas where it had current or past operations.

[7] “War, rain and money – an anatomy of South Sudan’s food crisis: Millions of people in South Sudan need food aid,” Stephen Graham for IRIN [Juba], 19 June 2014

Across a swath of South Sudan, fields where green shoots should be poking through the wet soil lie untilled and overgrown; herds of cattle that would sustain communities through the lean season have been lost or stolen; food stores have been looted or burned.

The people of South Sudan, the world’s youngest and one of its poorest nations, are accustomed to hardship. But six months of war has uprooted so many of them and destroyed their meagre livelihoods that some four million require humanitarian assistance. Relief workers scrambling to avert a famine report daunting obstacles: from the failure of South Sudan’s feuding leaders to halt the conflict, to near-impossible logistics and limited international attention and resources. “The biggest single obstacle is the absence of peace,” Toby Lanzer, the top UN humanitarian official in South Sudan, told IRIN. “You still have a lot of people on the move, the continuation at least of a threat of violence breaking out at any stage.”

According to UN figures, about 1.5 million people have fled their homes since December, when fighting broke out between supporters of President Salva Kiir and those of his former deputy, Riek Machar. Thousands have died in the violence, including many civilians brutally targeted because of their ethnicity. The failure of international pressure to stop the fighting before the planting season has prompted increasingly loud warnings that starvation could lead to far more deaths unless beleaguered civilians receive urgent – and sustained – assistance. A survey carried out in May by government agencies and food security experts forecast that 3.9 million people, or one-third of South Sudan’s population, would face ‘crisis’ or ‘emergency’ levels of food insecurity by the end of August, up from 1.6 million a year earlier.

‘Crisis’ and ‘emergency’ represent levels three and four on the widely-used Integrated Food Security Phase Categorization (IPC) scale. Level five is “famine”, defined by the IPC as “the absolute inaccessibility of food to an entire population or sub-group of a population, potentially causing death in the short term.” For a famine to be declared, several conditions have to be met, notably a crude death rate of two per 10,000 people per day and a general acute malnutrition rate greater than 30 percent. In rural communities, families would normally store stocks of food to see them through to the next harvest.

But the displaced generally left their supplies behind, and host communities have had to share with relatives and strangers. Families have lost their livestock to theft, either by rival communities or ill-fed fighters from either side. In addition, traders who would bring foodstuffs from neighbouring countries such as Uganda and Sudan and exchange it for local commodities have been absent for months because of the fighting. Salt, for example, is almost impossible to find in some areas, Lanzer said. UNICEF, the UN Children’s Agency, said in April that the number of children under five years of age suffering severe acute malnutrition across South Sudan had reached 223,000, or double the total before the crisis. It warned that 50,000 of them could die this year unless they received assistance, such as therapeutic feeding.

Relief agencies identify the southern counties of Unity State and parts of neighbouring Jonglei among the most critically affected areas of the France-sized country. In Unity’s Panyijar county, thousands of families from the surrounding area have taken refuge on islands in vast marshlands west of the White Nile River. Relief officials say many are subsisting on water lilies and tree leaves – a traditional fall-back in lean times. World Food Program airdrops have brought some relief, but aid workers say malnutrition levels there are soaring.

Medical charity Medair said almost half of the 4,500 children it had screened in Panyijar since April were malnourished. It found that families were increasingly concentrating their meagre rations on their strongest offspring. “They want all their children to survive but they are worried that they will lose them all,” Medair spokeswoman Wendy van Amerongen said. Hopes of trucking food and other emergency supplies to isolated areas before the rains made many roads impassable were dashed by continued insecurity…. With most main roads impassable, WFP has had to focus on airlifting and airdropping supplies, mostly using huge Russian-built Ilyushin cargo planes. To make sure the rations reached the most needy, and help prevent aid being seized by combatants, Sackett said WFP was inserting small “hit-and-run” teams into crisis zones for little more than a week to assess requirements, register those in need, and oversee the airdrops and the distribution.

Other partners were vaccinating children and distributing seeds at the same time. He said WFP enjoyed considerable goodwill from the two warring parties – a legacy of its massive aid operation in the 1990s during Sudan’s long civil war – and that this helped keep its aircraft and ground teams safe. However, Sackett said his agency simply doesn’t have enough food to meet the needs.

Donors including the United States and United Kingdom pledged an extra US$600 million at a May conference in the Norwegian capital, Oslo. However, the UN says it is still US$800 million short of what is needed for this year alone. Sackett said it was still unclear how much of the new money would be allocated to WFP. “Even post-Oslo, we really haven’t seen any surge of new confirmed pledges that we can translate into physical food,” he said. Plans to distribute 17,000 tons of food in June, for instance, were probably not possible because of a “constrained pipeline,” he said. “We are overcoming the logistic constraints by more and more aircraft, but we don’t have the food to get up to the plan.”

The humanitarian effort has faced bureaucratic hurdles.

Lanzer said UN officials spent weeks persuading the government to remove dozens of checkpoints along the few main roads still open. Unofficial taxes were adding 4,500 Sudanese pounds (US$1,200) to the cost of delivering a truckload of supplies. The UN also persuaded the government to streamline customs and immigration procedures for aid workers and relief goods. The environment brings other challenges. In Bentiu and Panyijar, planes have been unable to land after rain because the airstrip becomes too boggy. The UN is negotiating with oil companies to get access to an all-weather strip north of Bentiu.

Still, UN agencies have reached over 80 locations in the past six months, mostly by air. The cost and limited capacity of even the largest aircraft means WFP is looking to send food barges up the White Nile, despite the hazards. In April, unidentified attackers fired guns and rocket-propelled grenades at barges carrying food and fuel to a UN base in Malakal, another tense northern town, injuring four crew members and UN peacekeepers. Lanzer said it was difficult to persuade barge operators to try again. But by early June, workers in Juba were loading food onto a convoy of barges that will have to cover the same route through both government and opposition controlled territory.

WFP officials were already negotiating with local power-brokers to try to ensure their safe passage. “They are also passing through areas where people are probably pretty hungry … so there are three main threats,” Sackett said. For civilians, the rainy season brings some respite. With richer grazing, cattle produce more milk, while wild foods and fish can be more plentiful. Moreover, the first so-called ‘green’ harvest comes in September, ahead of the main crop in November. But yields are expected to be meagre in the north and east, where the fighting has primarily raged. Once those crops are used up, the food crisis is expected to intensify. “From the end of this year, we will be plunging into a long lean season that will go right up to the September 2015 harvest,” Sackett said. “The likelihood of problems is certainly greater this time next year than it is now.”

[8] “100,000 people in UN-protected sites in South Sudan,” (Radio Tamazuj, 20 June 2014)

Fear and hunger continue to drive people to UN-protected sites in South Sudan, with the population of these sites now reported to be about 100,000; Doctors Without Borders/MSF finds that 3 children dying per day in Bentiu Camp Medical charity Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) warned Thursday of an “alarming number of deaths” from disease and hunger in Bentiu, Unity State.

[9] “OCHA: Bentiu camp “sharply” deteriorates, could hit 60,000 people,” Radio Tamazuj [Juba], 22 June 2014)

The United Nations’ humanitarian arm reported as of 20 June worsening conditions for civilians in the UN base in Bentiu, capital of South Sudan’s Unity State, and that the population in the already overcrowded site could soon hit 60,000 people. “Living conditions for the up to 46,000 displaced people sheltering in the UN base in Bentiu deteriorated sharply,” read the weekly bulletin of the Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

“The number of people in the base could increase to 60,000 in the coming weeks.” Around 100,000 people are sheltering in the UN’s bases in South Sudan, most fleeing the civil war that began in mid-December. Bentiu is already severely overcrowded, with “thousands” of malnourished people pouring in over the last two weeks. OCHA said aid agencies could only supply “4-9 litres of water per person per day, far below the SPHERE standard of 20 litres,” and that there are 234 people per latrine.

“Another 721 latrines were urgently needed to meet the emergency standard of one latrine for every 50 people,” the bulletin read. OCHA said there have been 599 cases of severe acute malnutrition among children and that over 100 children have died in Bentiu’s base over the past six weeks, mostly from diarrhea, pneumonia, and malnutrition, diseases which thrive in unsanitary, cramped conditions.

[10] “MSF says displaced dying at alarming rate in Unity state,” June 20, 2014 (JUBA)

Preventable diseases and severe acute malnutrition are causing alarming death numbers among an estimated 45,000 people taking refuge at the United Nations base in Unity state capital, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) said Friday. The situation, the medical charity warned in a statement, could worsen unless there was rapid increase in water supplies, hygiene promotion and latrine construction. According to MSF, the number of people seeking protection at the base increased nearly tenfold in the last two months due to relentless violence in Unity State, while recent flooding has left the area without enough clean water or sanitation facilities.

Medical reports from the camp also show that at least three children under 5 years were dying per day within Bentiu’s protection of civilian sites. Most of the deaths are reportedly due to acute diarrhoea, pneumonia and malnutrition linked to the existing harsh conditions. “People came here for safety but they are facing life-threatening conditions inside the camps,” said Nora Echaibi, medical team leader of an MSF hospital on site. “It is rapidly becoming catastrophic”, she added. Recent heavy rains exacerbated an already grim situation, flooding latrines and making it impossible for water trucks to use the roads for deliveries.

Medical facilities and other areas where aid organizations provide services have been flooded. As of mid-June, wells and tanker trucks are supplying only 4.4 litres of clean water per person per day, which is far below the international standard of 15 litres and residents are forced to drink from puddles that are often contaminated with human waste. The area reportedly has only one working latrine serving an average of 241 people daily.

Displaced people continue to arrive every day from surrounding regions in very bad conditions after walking long distances or surviving for a long time in the bush without food and assistance. Ongoing hostilities make it impossible to use the roads safely, even to collect supplies such as sand, which is essential to protect areas from flooding. Due to the flooding of the roads, all materials have to be transported by plane at high cost.

This is how many children will soon look without a substantial increase in humanitarian funding

[11] “Humanitarian responses should address vulnerable needs,” Sudan Tribune [Bor], 20 June 2014

A top United Nations official, who visited Jonglei’s state capital, Bor Friday expressed concerns over the worsening humanitarian conditions among the displaced people living in camps. Panos Moumtzis, a senior UN humanitarian advisor, led a team of eight people to Jonglei, one of the three states badly-hit by the mid-December 2013 violence. The visit, he said, was to encourage humanitarian agencies to reach conflict-affected communities in largely insecure areas of Akobo, Nyirol and Uror. “We want to make sure that the humanitarian response meets the needs of the people on the ground, and we are looking into how better (we can) improve our humanitarian response”, said Panos.

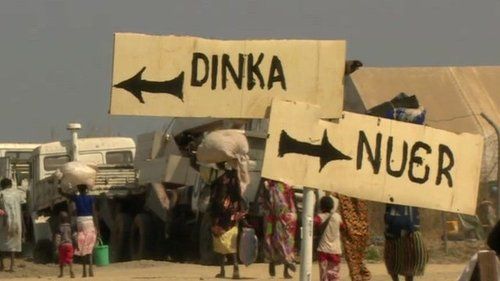

He stated that humanitarian involvement in crisis management, through provision of humanitarian aid, would not solve the ongoing suffering of people in Jonglei and South Sudan in general. “I clearly think humanitarian assistance is not an answer to the current crisis although we do our best to provide assistance”, said Panos. During the team’s visit, however, concerns were expressed about the presence of the Nuer displaced people in the UN compounds in Bor. Poor health conditions, lack of shelter and food were identified as some of the issues people facing the population in the civilian protection site in Bor. Nearly 6,000 individuals, mainly from the Nuer ethnic tribe, sought protection at Bor UN compound after violence broke out in the state on late December 2013.

On 17 April, about 60 people were killed at the UN premises when armed youth stormed the protection site demanding relocation of the displaced civilians, according to Jonglei state officials. The state information minister, Jodi Jonglei, said the government would cooperate with humanitarian agencies to better the lives of the conflict-affected people and that peace was the only solution.

[12] Medair in South Sudan reports via Twitter (June 24, 2014) that it has “screened over 6500 children in Panyijar County (Unity State). About 47% of them are malnourished.”

The ethnic violence tearing South Sudan apart must end for even the most robust humanitarian response to be effective