“Janjaweed Reincarnate: Sudan’s New Army of War Criminals,” Akshaya Kumar and Omer Ismail, Enough Project, June 2014 | http://www.enoughproject.org/files/JanjaweedReincarnate_June2014.pdf •

This report, based on extensive research, consolidates and expands what we know about the “reincarnated” Janjaweed. I have argued for a number of years that the Janjaweed never disappeared from the scene in Darfur; rather, they were “recycled” into other security and paramilitary forces (e.g. Central Reserve Police (Abu Tira), the Border Intelligence Guards, the Popular Defense Forces, and indeed the Sudan Armed forces). At the same time, this timely report makes several important observations about the differences between the Arab militia forces of the earlier years of the genocide in Darfur and the current heavily armed and directly government-supported “Rapid Support Forces.” Below is a central excerpt from the report, containing numerous highly alarming facts about what has become the “new law” in Darfur. —ER

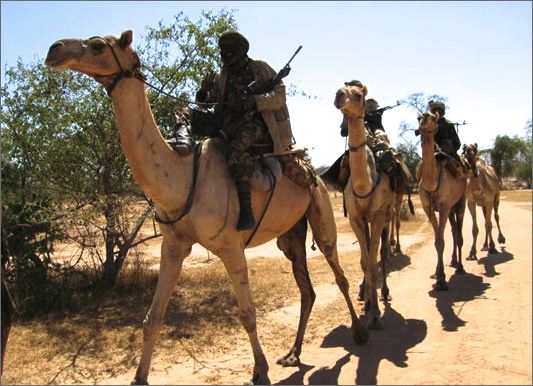

The Janjaweed of earlier years

From “Janjaweed Reincarnate: Sudan’s New Army of War Criminals” To breathe new energy into their fraying alliance with the Janjaweed, the Sudanese government offered a second life to one of its longtime clients: Mohammed Hamdan Dagolo, also known as “Hemmeti.” In exchange for recruiting a new force of 6,000 men, the militia commander was promoted to the rank of brigadier general within the NISS and given state-issued identification cards to sell to recruits. These cards entitle bearers to legal immunity under Sudan’s 2010 National Security Services Act and confer financial benefits from the state. In a May 2014 televised statement, the RSF’s Khartoum based commander Maj. Gen. Abbas Abdul-Aziz publicly confirmed that a majority of the members in the force “are Darfurians” recruited by Hemmeti. Since then, the Sudanese government has announced the creation of a new RSF-2, allegedly mostly composed of recruits from South Kordofan.

Under Hemmeti’s command, many original Janjaweed commanders have become officers in the RSF. Today’s fighters, however, are operating under vastly different circumstances from those under which the rag-tag militias that conducted the first wave of the Sudanese government’s genocidal campaign operated. Three significant changes are evident. First, these forces are better equipped. They also come under central command and are fully integrated into the state’s security apparatus. Second, they have legal immunity under Sudanese law from prosecution for any acts committed in the course of duty. Finally, although they were recruited in Darfur, the troops have been deployed around the country at the command of the Sudanese government. These forces also play a role in broader transnational criminal looting and poaching networks, adding a regional dynamic to their activities.

Complete integration

Today’s RSF fighters are far better equipped; they come under central command and are more fully integrated than the Janjaweed militias that the world came to fear in 2003. The newly launched army of war criminals is, however, engaged in the same type of ethnic cleansing campaign as the waves of fighters who came before them and fought under the command of militiamen like Musa Hilal and International Criminal Court (ICC) indictee Ali Kushayb. The Sudanese government has previously completely denied association with the Janjaweed militia forces. For their part, the feared Janjaweed fighters were difficult to engage, making it hard to challenge the government’s assertions. An Australian Broadcasting Corporation documentary sought out members of Janjaweed forces in 2006 to hear their side of the story.

Seizing the opportunity to speak to a Western audience, Hemmeti—who now commands the RSF—proclaimed to the camera that he was personally recruited by Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir to join the fight. In the interview, Hemmeti bragged that President Bashir asked him to carry out campaigns in northern Darfur during a meeting in Khartoum in 2003. At the time, this admission was groundbreaking. Up until that point, the Sudanese denied association with the Janjaweed militia forces. For their part, the feared Janjaweed fighters were difficult to engage, making it hard to challenge the government’s assertions. Up until that point, the Sudanese government had successfully portrayed these fighters as uncontrollable bandits and thugs. Later, Julie Flint and other researchers spent months with Hemmeti and other Janjaweed groups, seeking to understand their motivations. After a brief rebellion against the government, Hemmeti told International Crisis Group researchers, “We just wanted to attract the government’s attention, tell them we’re here, in order to get our rights: military ranks, political positions, and development in our area.”

Unlike the first wave of Janjaweed fighters in 2003 through 2005, who were desperate to tell the world about the state’s endorsement of their actions, this incarnation of the forces has no need to seek that type of affirmation. Hemmeti holds the rank of brigadier general. His RSF fighters carry the symbols of the NISS with them wherever they go. The NISS maintains a Facebook page that showcases the group’s activities. The Sudanese Embassy in Washington, D.C., distributes a fact sheet about the force. Senior RSF commanders hold public press conferences at government headquarters to defend their reputations. The government fact sheet on the RSF insists that the “RSF operates under disciplined military system and orderly chain of command. It’s (sic) movements and operations are fully controlled and governed by military laws and regulations.” Following a public parade in honor of the RSF, Ishraqa Sayed Mahmoud, Sudan’s minister of human resources development and labor, announced a financial donation to the RSF, congratulating them on the victories and noting that the “Sudanese people are appreciative of the sacrifices made by these forces.”

In late May 2014, the Director of NISS operations, Maj.-Gen. Ali Al-Nasih al Galla, the director of NISS support and operations forces, reaffirmed that “more than six thousand [RSF] security personnel are distributed at petroleum sites, co-deployed with the armed forces at borders and co-working with police to protect the national capital and other major towns.” Since that time, analysts report that the RSF’s ranks have swelled to at least 10,000 troops, 3,300 of which are stationed in Khartoum. The government’s own accounts reference the creation of a second RSF force specially focused on South Kordofan, raising the possibility that additional troops operate under the RSF banner. The newly recruited RSF troops obtained training from Sudan’s NISS and army high command. In early February 2014, Sudan’s opposition Popular Congress Party reported that at least 5,500 Janjaweed fighters received special training at bases north of Khartoum. Reliable sources confirm that the RSF troops trained with both the NISS and the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) at the Wadi Seidna and Al Jayli bases north of Omdurman and Khartoum, respectively. According to Hemmeti himself, senior NISS officials, including former Sudanese Prime Minister al-Sadiq al Mahdi’s son Bushra al-Sadiq al-Mahdi, were involved in the forces’ training program.

Once the RSF formally launched, the SAF actually reassigned its personnel to command the new forces. SAF Maj. Gen. Abdul-Aziz shares control over the forces. Additionally, Gen. Ali al-Nasih al-Galla, a senior NISS official, retains overall control as superior to both Hemmeti and Maj. Gen. Abdul-Aziz. In mid-May 2014, Gen. al-Galla evidenced his role as overall commander of the RSF when he promoted 35 Janjaweed officers to higher ranks within the RSF fighting force. Beyond this, it is difficult to trace command responsibility. According to Magdi el Gizouli, a fellow at the Rift Valley Institute, “The chain of command above [Hemmeti] and his men, it follows, is camouflaged by design to allow the officers at the helm to claim victory when it happens but avoid culpability for the carnage.” RSF commander Hemmeti has been pictured with Sudan’s Minister of Defense, Abdelrahim Mohamed Hussein, as well as with Ahmed Haroun, one of the original commanders of the Janjaweed. Both men are wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes and crimes against humanity in Darfur.

Full immunity

As members of the NISS, the RSF carry formal immunity for all actions. Under Sudan’s 2010 National Security Act, NISS agents are immune from prosecution and disciplinary action for all acts committed in the course of their work. Although the law does allow for the director of the NISS to waive immunity, this de facto blanket protection creates a climate of impunity. The Sudanese government fact sheet maintains that the “RSF includes discipline and control units such as military police, intelligence and military judiciary.” In practice, however, NISS agents are seldom taken to court, even in instances where they are alleged to have tortured detainees or committed serious human rights abuses. As Gizouli explains, “If the Janjaweed operated in a zone of legal immunity, [Hemmeti’s] forces constitute the law.”

All footnotes may be found in the ful report at: http://www.enoughproject.org/files/JanjaweedReincarnate_June2014.pdf

What the Janjaweed left in their wake (top photograph by Brian Steidle; bottom two photographs by Mia Farrow)

What the Janjaweed left in their wake (top photograph by Brian Steidle; bottom two photographs by Mia Farrow)