UNAMID Withdrawal and International Abandonment: Violence in Darfur 2017 – 2019, a statistical analysis

Eric Reeves, author; Maya Baca, research, data collection, and editing – May 20, 2019 | https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qm

Report/Data Introduction

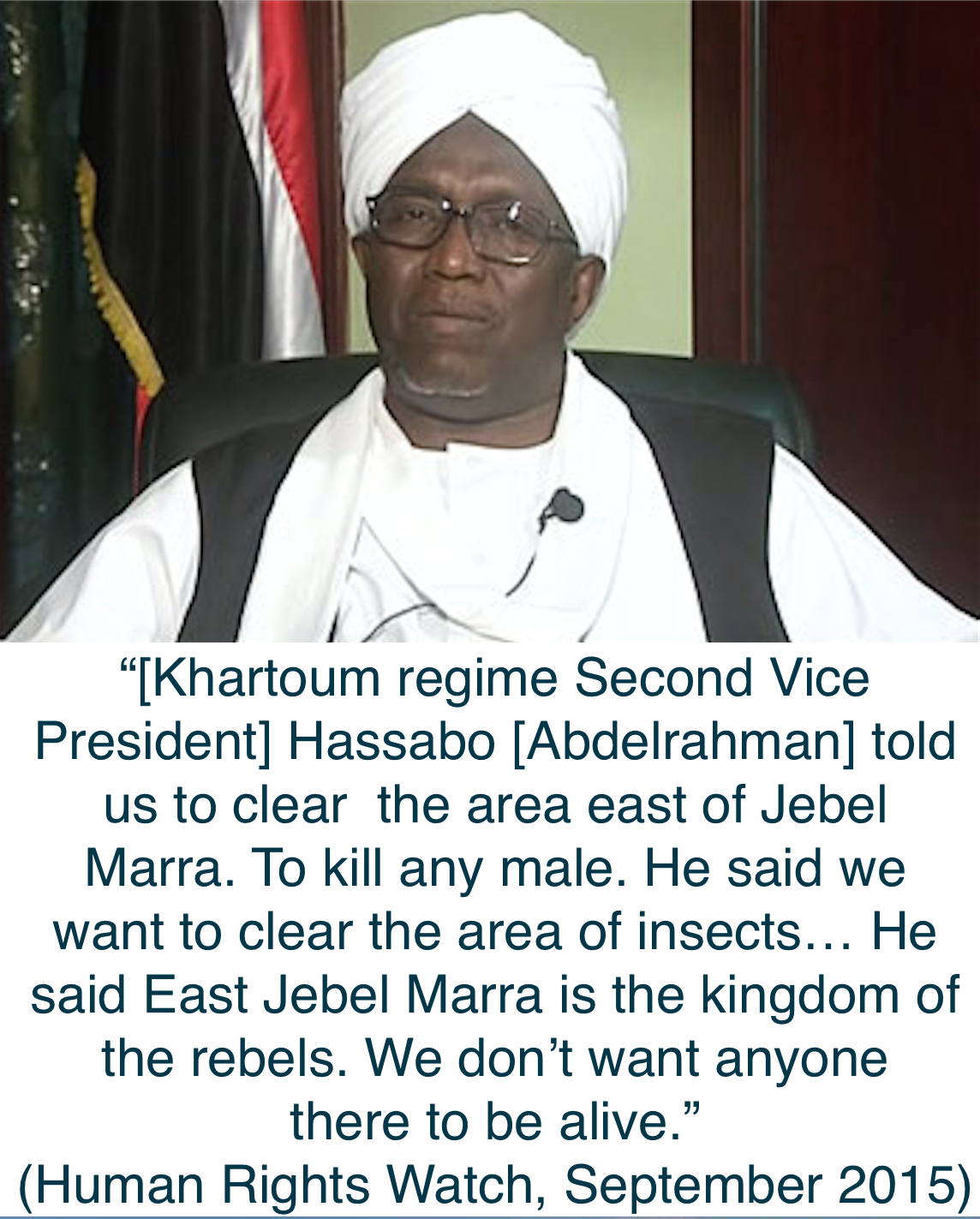

This brief monograph attempts to give as comprehensive an overview as possible of violence during a period in which the international community has largely abandoned efforts to protect civilians, specifically the non-Arab/African[1] populations of Darfur. Although Arab groups have suffered from significant violence at various points over the sixteen years of the Darfur conflict, particularly inter-tribal violence in East Darfur—and continue to suffer from violence in some areas—the genocidal ambitions of the Khartoum regime’s counter-insurgency campaign against Darfuri rebel groups has been directed overwhelmingly at non-Arab/African tribal groups. For this reason, human rights and Sudanese democracy groups have long warned about the ominous consequences of a premature removal of what is primarily a protection force for civilians and humanitarians.

Although the period broadly surveyed here includes all years subsequent to my 2012 archival history of Darfur and greater Sudan, the focus is on the years 2017 to the present. During this time there has been no report on Darfur from a major human rights organization. My own two monographs on violence during the years 2014 – 2015 provide what I think is a representative account of the period 2012 – 2015; moreover, these two documents comport extremely well with the two important reports from Human Rights Watch in 2015 and a major report on the military campaign against Jebel Marra released by Amnesty International in 2016 (these reports, as well as my monographs, appear in the accompanying Bibliography).

[The actual data sets and mappings of the data collected for the present analysis appear at the end of this monograph]

The period January 2017 to the present is significant not only because of the extent of continuing genocidal violence directed against non-Arab/African civilians, but because it is the period during which the peacekeeping operation of the UN and African Union began the process of withdrawal—a withdrawal based on serious misrepresentation of the levels of continuing violence and civilian insecurity in Darfur, and the corresponding need for effective protection.

The grim truth, tragically, is that UNAMID (UN/African Union Mission in Darfur)—an unprecedented “hybrid” mission—has been a grotesque failure, perhaps the most serious in UN peacekeeping history (for recent assessments of UNAMID performance, see | https://wp.me/p45rOG-2oy/). Since its official deployment in January 2008—over eleven years ago—it has allowed itself to be thoroughly compromised in all ways by the Khartoum regime. Indeed, Khartoum’s militia forces have repeatedly attacked UNAMID contingents, sometimes in deadly fashion. These attacks have sometimes been confirmed by UN officials, although without holding the al-Bashir regime accountable.

The “Status of Forces Agreement” negotiated by UNAMID (January 2008), allowing timely and unfettered access throughout Darfur, was a supreme example of the al-Bashir regime’s bad faith. Such unfettered access was never the case, and indeed Khartoum has repeatedly, pointedly, and consequentially denied both protective and investigative missions by UNAMID for the entire term of its deployment. Even as it was in the midst of planning for withdrawing entirely from Darfur, UNAMID was impeded and restricted in its movement. One finds in the reporting record constant dispatches such as this:

Sudan restricts UNAMID’s movement, says force commander | Sudan Tribune, May 9, 2018 (KHARTOUM) | UNAMID Force Commander, Leonard Muriuki Ngondi, Wednesday said the Sudanese government has often restricted the Mission’s freedom of movement…

The force itself has become hopelessly demoralized, and is given a shabby “success” only in the form of egregious misrepresentations by UNAMID officials and the UN (particularly the Secretariat and Department of Peacekeeping Operations).

[One reason that the reports of the UN Panel of Experts on Darfur figure so little in my assessment here is the failure of UNAMID to provide the access necessary for the Panel to do its reporting work. In the early years of the Panel—established by UN Security Council Resolution 1591 in March 2005—some very helpful reports emerged. But the Panel became increasingly politicized. With growing obstruction by the Khartoum regime and the Panel’s dependence on UNAMID for logistics and security clearances, its reports have devolved into largely meaningless accounts of the level and nature of violence in Darfur.]

Moreover, as UNAMID has begun to withdraw from various bases in different areas of Darfur, these bases have been converted by the Khartoum regime for use by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), in violation of commitments made by Khartoum (including the Status of Forces Agreement) and in violation as well of international law. Publicly UNAMID officials declare its bases are or have been converted to civilian uses, as stipulated in agreements with Khartoum. I have been informed, however—by a source with authoritative access to UNAMID officials and thinking—that UNAMID admits privately that all but one of the bases it has surrendered have been converted to use by the RSF. UNAMID itself has expressed concern about the transfers, but has not changed plans that result in augmentation of the RSF. There could be no grimmer conclusion to the work of UNAMID over the past eleven years. All this duplicity and acquiescence is of course well known to rebel groups on the ground and works in part to account for their suspicions of international mediation efforts. (Appendix A gives a timeline for UNAMID withdrawal by means of the consistently useful Sudan Tribune updates on decisions by the Mission leadership and the UN Security Council).

All this duplicity and acquiescence is of course well known to rebel groups on the ground and works in part to account for their suspicions of international mediation efforts. (Appendix A gives a timeline for UNAMID withdrawal by means of the consistently useful Sudan Tribune updates on decisions by the Mission leadership and the UN Security Council).

REPRESENTING VIOLENCE IN DARFUR

By “violence” in this monograph I mean not only actual physical assault, including rape, murder, and abduction, but actions by the various elements of the Sudan Armed Forces, militia forces (particularly the Rapid Support Forces, or RSF), and the various armed elements that have created an intolerable level of insecurity among a wide range of civilian populations, many of which have been either newly displaced, seen their lands violently expropriated, or experienced terrible agricultural losses, either by deliberate destruction (including cutting down or burning of mature fruit trees) or allowing livestock to graze on cultivated and fruitful lands.

I should emphasize that a great deal has not been included, and this should be borne in mind when examining the final mapping of the data for violence on five separate maps: South Darfur, what is now “East Darfur,” West Darfur, what is now “Central Darfur,” and North Darfur.

Important categories of reporting not represented in this mapping include:

• Many reports of arrests—or of releases following arrests (arrests in which abuse or torture is a clear possibility have been included);

• Executions, if “legally” carried out;

• Civil society protests and strikes;

• Self-serving “news” from UNAMID (which is typically disingenuous and/or incomplete);

• Road accidents;

• Fires—all too frequent in the camps—are not included unless there is some suggestion of arson (a notoriously difficult crime to prove, even with willing investigators). And it must be borne in mind that the very nature of IDP camps—with often flimsy shelters and dangerous cooking circumstances—makes them extremely vulnerable to fire, especially in the dry season;

• Humanitarian issues, unless they are directly related to ongoing violence;

• Non-violent criminal activity and law enforcement, including the ongoing campaign against cannabis trafficking and the many thefts reported in IDP camps, with the perpetrators from outside the camps;

• Reports on the Khartoum regime’s “disarmament campaign,” unless these reports include violent consequences to confiscation of weapons. In general, it should be noted that the “disarmament campaign” disproportionately targeted non-Arab/African civilians, and has been an excuse for a great deal of the violence of the past two years and more. The use of the RSF for “disarmament” has ensured that this often undisciplined force has severely abused its powers;

• Military developments outside Darfur, including violence in South Kordofan and Blue Nile, and military casualties in Yemen, most of them from Darfur (and a great many of them children):

South Darfur receives bodies of 17 militiamen killed in Yemen | Sudan Tribune, November 11, 2018 (NYALA) | At least 20 fighters from the government militia Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have been killed and more than 100 wounded in the fierce fighting that has been going on for days in Yemen, a reliable source told (…)

21 Sudanese troops killed in Yemen: Military sources | Sudan Tribune, May 27, 2017 (KHARTOUM) | Sudanese military sources Saturday have dismissed media reports that 80 Sudanese troops have been killed in Yemen saying only 21 were killed, including 4 officers. Sudanese soldiers carry the coffin (…)

Finally, it falls outside the scope of this report to chronicle in detail the brutal treatment of Darfuris seeking to escape the region via Libya. They have frequently been victims of terrible violence: kidnapped, tortured for ransom in torture centers, detained in no less violent official detention centers, and forced to work as slaves. They have also been forcibly recruited as fighters. In Niger many have been deported to Libya; many more have drowned in the Mediterranean. It is also the case that the Rapid Support Forces have been authoritatively shown to be trafficking in migrants, including Darfuris. Migrants smuggled by the RSF are often sold to Libyan traffickers. See on this topic:

“Multilateral Damage: The Impact of EU Migration Policies on Central Saharan Routes,” Clingendael, September 2018 | https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2018/multilateral-damage/

“Remote-Control Breakdown: Sudanese paramilitary forces and pro-government militias,” Small Arms Survey (Switzerland), April 2017 | http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/issue-briefs/HSBA-IB-27-Sudanese-paramilitary-forces.pdf

CONTEXT FOR THIS REPORT

This monograph has been prepared with the extraordinary national uprising in Sudan as backdrop (beginning December 19, 2019). The ferociously determined and morally urgent demonstrations have focused on a single goal: removing the al-Bashir regime—and all vestiges of the “deep state” his regime created over thirty years—as a way of restoring peace, freedom, and justice, however imperfectly. The fate of Darfur is in many ways being determined even as I write these words; there is, nonetheless, much evidence that violence and insecurity remain at intolerable levels, despite the disingenuous, expedient, and often mendacious claims from the UN and African Union.

I would again note in particular the continuing attacks of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), essentially those under the command of Lt. General Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, more commonly known as “Hemeti.” Hemeti, as I will refer to him, has assumed a position in the Transitional Military Council (TMC) now governing Sudan that makes him the equivalent of “Vice President”—second in command to his colleague in Darfur atrocities and the military activities of Sudan in Yemen, Abdel Fathah al-Burhan, head of the TMC. Attacks by the RSF on peaceful civilians continue in Darfur and South Kordofan, and there is no evidence that Hemeti is using his now immense (and growing) power to restrain these forces. Very recent reports (May 9, 2019) of violence against demonstrators have specifically pointed to the RSF as the responsible party.

The Sudanese Doctors Central Committee estimates that at least 90 people have been killed violently by regime elements during the current uprising. Estimates of the number of RSF troops under Hemeti’s command in the greater Khartoum urban area reach to 15,000—an army unto itself (although formally incorporated into the Sudan Armed Forces, the commander of the RSF is not in the army’s regular chain of command). It is Hemeti’s RSF who have been responsible for most of the genocidal violence in Darfur since the Force was constituted in 2013. (See Jerome Tubiana, “The Man Who Terrorized Darfur Is Leading Sudan’s Supposed Transition,” Foreign Policy, May 14, 2019.)

European countries, the U.S., and many other important state actors in Africa, the Arab world, and Asia have allowed narrow national self-interest to define Sudan policies, policies that encouraged the al-Bashir regime to believe that even the most ruthless and brutal crackdown on demonstrators would not bring real, consequential international pressure. Some countries, especially Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, as well as Russia and China, have actively supported al-Bashir and now his successor regime, the Transitional Military Council. To my knowledge, not a single Arab or African country has uttered anything like a full condemnation of the savagery by the Khartoum junta’s security forces, savagery that rages across the country.

Darfur has of course not been spared; but in addition to the violent repression of political protests, intolerable levels of violence and insecurity keep some 2.5 million Darfuri people trapped in camps for internally displaced persons and refugees in eastern Chad.[2] Despite their terrible conditions, the camps may soon suffer a grimmer fate: exactly a year ago, then-President al-Bashir promised that as a way of restoring Darfur, “the government would work to dismantle the IDPs camps.”

This vast population—more than a third of Darfur’s pre-war population—has nowhere to go, despite grand promises by al-Bashir and other regime officials that “services” and “new villages” would be provided. The simple fact is that there are neither the economic means nor any meaningful commitments to address the massive needs of this vast population: in the main their villages and lands have been destroyed or seized by Arab forces or settlers. And yet still the determination to “dismantle” camps, especially those perceived as troublesomely “political,” is urged as regime policy:

South Darfur governor reiterates threats to dismantle Kalma camp | Sudan Tribune, April 26, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – The governor of South Darfur State Adam al-Faki Thursday repeated threats that his government is determined to dismantle Kalama camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) and threatened to arrest the arrest the camp’s leaders who are accused of inciting the residents to reject returning to their areas of origin.

Those who attempt to return to their homes are typically greeted with hostility and violence. They are celebrated by the UN and African Union for “returning,” but typically no mention is made of the countless failed attempts to return, resulting in people going back to the camps, or being killed. It is for these very reasons they stay in camps that are squalid, constantly at risk of violence, and desperately under-served; “dismantling” them—whatever “services” are promised—will create vast, deeply depressing slum suburbs of the major towns, although without employment opportunities, decent health care, or education. It is a shameful scandal that the world ignores this looming catastrophe in its efforts to negotiate “peace” in Darfur.

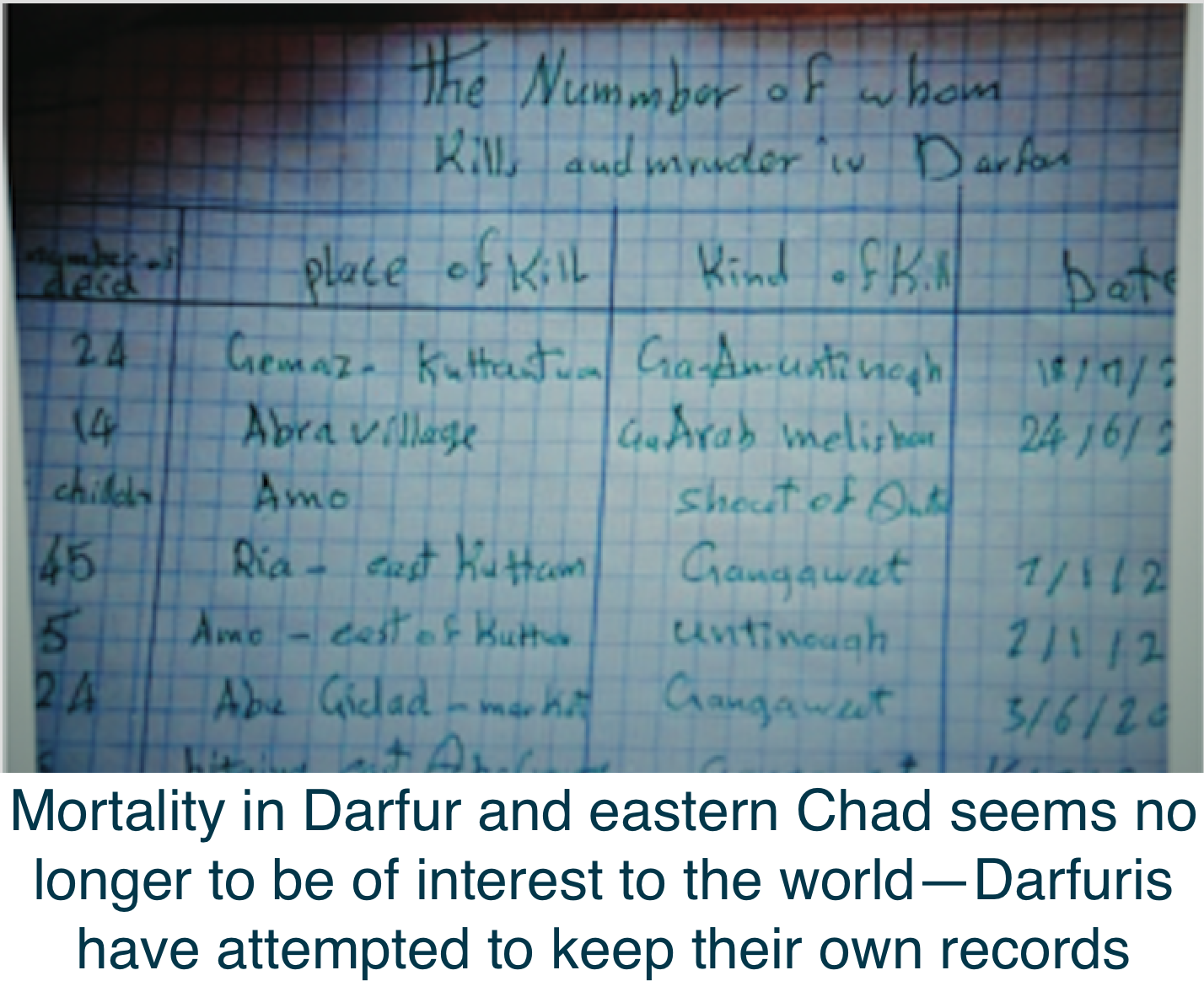

In fact, the only peace that has come after sixteen years of war is the peace of the dead. The grimmest statistic for the Darfur genocide is the mortality total: by my calculations, some 600,000 people have died as a direct or indirect result of violence loosed by the al-Bashir regime, targeting non-Arab/African villages, populations, and camps. The last UN estimate of mortality occurred in April 2008, when the UN head of humanitarian operations at the time, John Holmes, offered a figure of 300,000—the figure still almost always cited by current news reports. Over eleven years, there has been no update from the UN, no promulgation of data bearing on mortality, and no inclination to undertake this terrible reckoning. (I have received no meaningful critique of the data or methodology or conclusions in my analysis of August 2010 (updated 2012)—from the UN or any other source.)

Rape of girls and women also continues throughout all regions of Darfur, and my monograph of 2016 makes clear that while we can only estimate, based on all evidence I cannot believe that the total figure for sexual assaults on non-Arab/African girls and women is not in the many tens of thousands.

Unexploded Ordnance (UXO): There are continuous reports of people—primarily children—killed or badly injured by explosions of UXO. UNAMID has again failed badly in clearing the various regions of Darfur of these deadly objects, typically belonging to or fired by the SAF or RSF;

It should be noted—in ways the UN and UNAMID never do—that the overwhelming majority of displaced persons and victims of violence have been non-Arab/African. Given the continuing rates of ethnically-targeted human destruction and suffering—and what the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide specifies as “Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part”—it is important to underscore that genocide continues in Darfur, if with deaths directly resulting from violence significantly reduced from the most violent periods of the conflict (2003 – 2006, 2012 – 2016).

UNDERSTANDING THE REPORT DATA

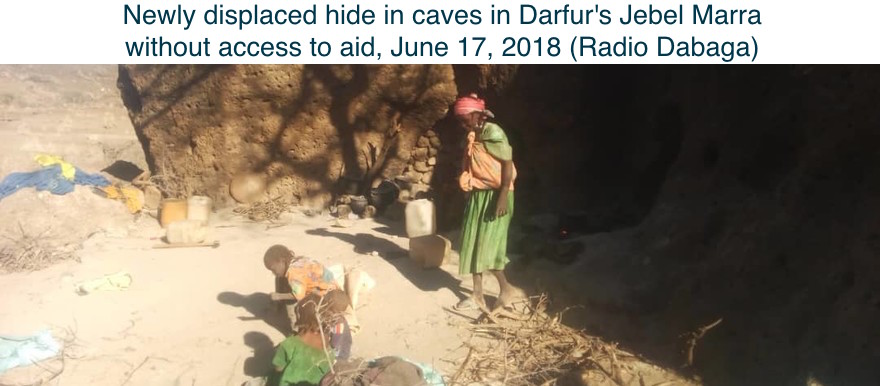

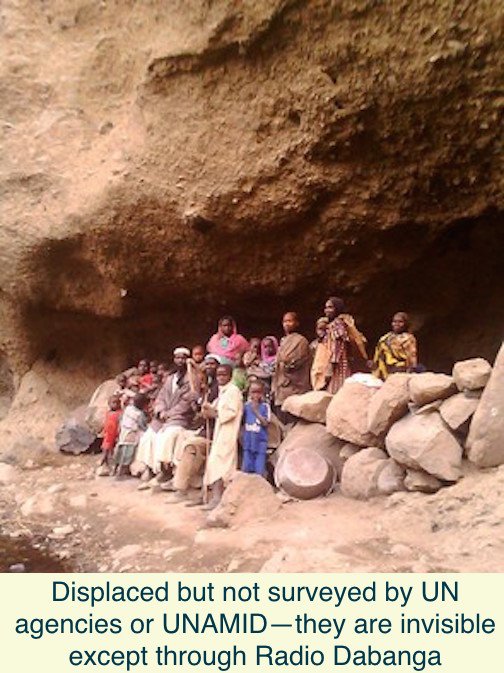

The data in this report comes mainly from Radio Dabanga, which continues to rely on an extraordinarily wide range of contacts on the ground in Darfur. Most dispatches concerning violent incidents have, in addition to dates, the locations of specific events, often names of victims, and detailed context for the violence. It is safe to say that without Radio Dabanga—given the appallingly inadequate reporting record of UNAMID—the al-Bashir regime would have succeeded in turning Darfur into a “black box” from which no information emanates.

In addition to the reports from Radio Dabanga—all represented in the data spreadsheet and data mapping—I have relied on numerous dispatches from Sudan Tribune and African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies (ACPJS), other open sources (especially human rights groups), as well as reports from confidential sources I know to be fully reliable.

Reports that have as their source rebel groups in Darfur are always indicated as such, but cannot be ignored simply because of sourcing concerns. Some information comes from confidential sources, unwilling to identify themselves publicly for security reasons.

The data generated from these dispatches can hardly be considered definitive; indeed, it is likely that many fewer than half the violent incidents have been reported by any source—perhaps as little as 20 – 30 percent. But they are so numerous that creation of data spreadsheets and subsequent data mappings is distinctly possible, and this gives us an approximate view of the scale and concentration of violence. The data comport fully with human rights reporting by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Small Arms Survey (see bibliography below). And this is the context in which we must judge the decision, accepted by all international actors of consequence, to withdraw UNAMID.

What becomes clear looking at the data collected in this report is that Darfur has been recently, and remains, a dangerous, violent, and highly insecure environment for non-Arab/African Darfuris (for an overview of a single month of violence from late 2018, see | http://sudanreeves.org/2018/11/23/a-very-violent-month-in-the-darfur-genocide/).

[A full explanation of the data appears below.]

DARFUR, GENOCIDE, AND THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY

The UN Security Council, UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations, the UN Secretary Generals, and the African Union Peace and Security Council have all given their blessing to the withdrawal of UNAMID, which however great its failings—and they are massive—provides at least the cover of international protection, primarily in the form of deterring even more brazen and larger violent attacks on civilians, especially those in IDP camps. East Darfur, South Darfur, and West Darfur are to see the complete withdrawal of UNAMID by June 2019—one month from now. All UNAMID forces are to be withdrawn from Darfur—including the still extremely violent regions of Central Darfur and North Darfur—by June 2020. This will mark the ignominious end to UNAMID’s terrible and shamefully profligate history. (Again, my detailed overview assessments of UNAMID’s relatively recent performance [2017 – 2018] can be found at https://wp.me/p45rOG-2oy/.)

UNAMID’s withdrawal thus confers a terrible distinction upon Darfur: it is site of the longest and most successful genocide in over a century.

Because the international community gives no sign of pushing for a new body to provide civilian protection in Darfur, it seems appropriate to survey the circumstances in which the victims of genocidal violence are being abandoned, as reflected in the most recent data concerning violence in the region. What we can see from the collated data is the scale and frequency of violence in the relatively recent past—this as a way of understanding what will confront the non-Arab/African populations of Darfur as the last remnant of protection is withdrawn; and absent success of the current popular uprising, provision of “security” will fall entirely to the new Transitional Military Council, and in particular its “new Janjaweed,” the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), involved in a tremendous number of attacks on civilians in camps and rural areas. Various Arab militia forces continue their predations as well, and all too often the local police—even if they are disposed to help—are overwhelmed by the sheer military force of the RSF.

UNAMID has never dared to confront either the Sudan Armed Forces or the Rapid Support Forces—or even investigate atrocity crimes without Khartoum’s explicit permission, which is typically denied. In this sense, withdrawal will not be as significant as it might have been had the Mission taken on its mandate. Withdrawal is most significant because it sends an incomprehensibly scandalous message to would-be génocidaires: “Genocide as a tool of domestic policy, including counter-insurgency efforts, can be successful.”

There can be little else to say about the failure of UNAMID—and the international community’s failure to make of UNAMID an effective force for halting genocide.

______________

Footnotes:

[1] I will use this combinatory phrase throughout as a means of skirting the controversy over nomenclature: while ethnicity is an enormously complex issue in Darfur, the fact remains that ethnic identity is highly significant and has become even more salient over the past fifteen years, particularly in ethnic self-identification. It is not accidental that the victims of militia and regular force attacks are overwhelmingly from the Fur, Massalit, Zaghawa, Berti, Bergid, Tama tribes. This is true whether we look at the vast population of internally displaced persons and refugees in eastern Chad, or those who have died directly or indirectly from Khartoum-sanctioned violence.

[2] In 2017 the UN OCHA figure for Internally Displaced Persons was 2.7 million/; the UNHCR figure for Darfuri refugees in eastern Chad in October 2018 was 337,000.

It is important to remember that the overwhelming majority of these people—displaced by violence and insecurity from their homes and lands—wish to return, but cannot because violence and insecurity remain at intolerable levels.

UNDERSTANDING THE DATA

The data underlying this report take three forms (all with separate links on my website): compilations of reports of violence from Darfur, the vast majority, as I have indicated, from the dispatches of Radio Dabanga, an extraordinary news organization in exile that has drawn from an extremely wide range of sources—in Darfur particularly, but Sudan generally as well. Having recently visited Radio Dabanga headquarters in Amsterdam, and followed the development of the news organization for more than a decade, I have complete confidence in its integrity. Dutch journalistic society has ensured that the same standards of integrity that obtain in other Western news organizations define Radio Dabanga.

I should note that as a matter of journalistic practice, Radio Dabanga does not identify the ethnicity of victims of violence, as Arab or non-Arab, even when specifically, nominally referring to what are Arab or non-Arab-tribes (e.g., Rizeigat, Fur, Massalit). Nonetheless the likely ethnicity of victims is often readily identifiable with a high degree of certainty, especially in rural areas. Various words have clear implications in these dispatches, e.g., “farm,” “farmers,” “crops,” “herders,” “riding on camels,” “militiamen,” “men in uniform,” “displaced person(s),” “camps,” and many others. We may be almost certain that the ethnicity of a 13-year-old girl raped by armed herders riding on camels as she collects firewood is non-Arab—and depending on the location (e.g., Jebel Marra), certainty only grows. In the data spreadsheets that grow out of the vast assemblage of news dispatches going back to January 1, 2017, the column identifying “ethnicity of victim(s)” should be understood as representing inferences of the sort I suggest above. Frequently the ethnicity is unknown; less frequently the ethnicity is clearly Arab.

Again, ethnicity in Darfur is a matter of great complexity; nomenclature is a matter of controversy. Moreover, “genocide” has become a term of debate with respect to Darfur, even as there can be no real doubt about the ethnically-targeted nature of destruction from the beginning of conflict in 2003. This targeting takes forms specifically identified in the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

All of these, to a greater or lesser extent, have defined the acts committed by the regular forces of the Khartoum regime or its militia proxies, increasingly the Rapid Support Forces of Lt. General Hemeti, Vice Chair of the Military Council that now exercises executive power in Sudan.

My other major source of current news in Darfur is Sudan Tribune, with a long history of reliable sources and a commitment to present conflict and violence in Darfur as accurately as possible. The Tribune often offers longer, more comprehensive dispatches on military movements and developments.

The broadest and in many ways most important perspective on violence in Darfur comes from the studies of Small Arms Survey (Geneva)—most notably:

“Remote-Control Breakdown: Sudanese paramilitary forces and pro-government militias,” Small Arms Survey (Switzerland), April 2017 | http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/issue-briefs/HSBA-IB-27-Sudanese-paramilitary-forces.pdf

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• HUMAN RIGHTS PUBLICATIONS INFORMING THIS STUDY

“Scorched Earth, Poisoned Air: Sudanese Government Forces Ravage Jebel Marra, Darfur,” Amnesty International, September 26, 2016 | https://www.amnestyusa.org/reports/scorched-earth-poisoned-air-sudanese-government-forces-ravage-jebel-marra-darfur

“‘Men With No Mercy”: Rapid Support Forces Attacks Against Civilians in Darfur, Sudan,’ Human Rights Watch, September 9, 2015 | https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/09/09/men-no-mercy/rapid-support-forces-attacks-against-civilians-darfur-sudan

“Mass Rape in North Darfur: Sudanese Army Attacks against Civilians in Tabit,” Human Rights Watch, February 11, 2015 | https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/02/11/mass-rape-north-darfur/sudanese-army-attacks-against-civilians-tabit

“Remote-Control Breakdown: Sudanese paramilitary forces and pro-government militias,” Small Arms Survey (Switzerland), April 2017 | http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/issue-briefs/HSBA-IB-27-Sudanese-paramilitary-forces.pdf

“Multilateral Damage: The Impact of EU Migration Policies on Central Saharan Routes,” Clingendael, September 2018 | https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2018/multilateral-damage/

PRIMARY PUBLICATIONS BY ERIC REEVES, 2015 – 2019

Books:

A Long Day’s Dying: Critical Moments in the Darfur Genocide (Key Publishing, 2007) (review commentary at http://www.sudanreeves.org/Article285.html)

Compromising with Evil: An archival history of greater Sudan, 2007 – 2012 (October 2012 in eBook format, www.CompromisingWithEvil.org) (review commentary at http://sudanreeves.org/2013/08/30/compromising-with-evil-an-archival-history-of-sudan-2007-2012-commentary/)

Monographs:

“‘They Bombed Everything that Moved”: Aerial Military Attacks on Civilians and Humanitarians in Sudan, 1999 – 2011,” May 9, 2011 (last updated 2015) | (analysis and bibliography of sources, 80+ pages with accompanying Excel spreadsheet, at | https://wp.me/s45rOG-7566

“‘Changing the Demography”: Violent Expropriation and Destruction of Farmlands in Darfur, November 2014 – November 2015,” Eric Reeves, author; May Baca research and editing. December 2015—includes framing analysis, extensive data spreadsheet covering all reported incidents of violence against farmers and farmland in Darfur, as well as a detailed mapping of these data onto three maps encompassing all of Darfur (monograph translated into Arabic) | http://wp.me/p45rOG-1P4

“Continuing Mass Rape of Girls in Darfur: The most heinous crime generates no international outrage” | January 2016 | Eric Reeves, author| Maya Baca, research and editing—includes framing analysis, extensive data spreadsheet for 2014 and 2015, as well as detailed mapping of these data onto three maps encompassing all of Darfur (monograph translated into Arabic) | http://wp.me/p45rOG-1QG

Op/Ed publications:

“Sudan could explode: Now is not the time for the U.S. to play nice with Khartoum,” The Washington Post (“Global Opinions”), December 16, 2016

“The World’s Abandonment of Darfur,” The Washington Post, May 16, 2015

“Don’t Forget Darfur,” The New York Times, February 16, 2016

“A Better Restitution for Darfur,” The New York Times, July 15, 2015

Academic publications:

“In the Absence of Will: Could genocide in Darfur have been halted or mitigated?” (chapter in Preventing Mass Atrocities: Policies and Practices, ed. Barbara Harff and Ted Robert Gurr | Routledge Studies in Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, 2018

“Armed Conflict in Sudan (Blue Nile, Darfur and South Kordofan),” Armed Conflict Survey 2018 (Routledge, 2018); edited by The International Institute for Strategic Studies

“Darfur: International Indifference has Created the Longest, Most Successful Genocide in Modern History,” (peer-reviewed) journal article for ABC-CLIO/Modern Genocide database (2018)

On-Line publications:

See | https://wp.me/p45rOG-2oA

Individual web-posted analyses have been organized by year and chronological order at | http://sudanreeves.org/archive/

OTHER PUBLICATIONS

Jonathan Loeb, “Time to Get Serious about Civilian Protection for Darfur,” Inter Press Service News Agency, December 20, 2016 | http://www.ipsnews.net/2016/12/time-to-get-serious-about-civilian-protection-for-darfur/

APPENDIX A – UNAMID deployment out of Darfur (dispatches in reverse chronological order:

2017

UNAMID completes closure of 11 sites in Darfur | Sudan Tribune, October 22, 2017 (KHARTOUM) – The hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) has handed over the Sudanese government 11 team sites as part of phase 1 of the reconfiguration process. “We have closed 11 team sites across Darfur (…)

UNAMID hands over three more team sites in Darfur | Sudan Tribune, October 17, 2017 (KHARTOUM) – The hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) has handed over three team sites in South and West Darfur states to the Sudanese government. In a brief statement seen by Sudan Tribune on Tuesday, the (…)

Sudan, UN, AU approve establishment of UNAMID base in Jebel Marra | Sudan Tribune, September 24, 2017 (KHARTOUM) – The hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) Sunday said the tripartite coordination mechanism on the Mission has approved the establishment of a temporary operating base in Golo, Jebel Mara. The (…)

UN official urges to authorise new UNAMID base in Darfur’s Jebel Marra | Sudan Tribune, July 22, 2017 (ZALINGEI) – The head of U.N. peacekeeping operations John Pierre Lacroix on Saturday paid a visit to Central Darfur State where he inspected the security situation and called to authorise the opening of a UNAMID base in (…)

UNAMID renews commitment to help bring lasting peace in Darfur | Sudan Tribune, May 24, 2017 (KHARTOUM) – The hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) has renewed commitment to exert every possible effort within its capabilities and mandate to assist the parties to the conflict to reach a lasting peace in (…)

2018

UNAMID is still waiting land for Jebel Marra base: UN chief | Sudan Tribune, January 6, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – In a recent report to the Security Council issued by the end of 2017, the UN chief said that Darfur hybrid peacekeeping mission has achieved progress in the implementation of phase one of the UNAMID (…)

UN, AU propose closure of UNAMID sites in Darfur except for Jebel Marra | Sudan Tribune June 11, 2018 (WASHINGTON) – UN Peacekeeping Chief, Jean-Pierre Lacroix, Monday proposed to close all the UNMAID sites in Darfur region expect the greater Jebel Marra area and to increase peacebuilding and development.

Security Council drastically cuts Darfur UNAMID ahead of full withdrawal | Sudan Tribune July 14, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – The United Nations Security Council unanimously decided to extend for one year the mandate the African Union-United Nations Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) and also to reduce the number of its troops in line with (…)

UNAMID to cut presence in Central Darfur in October: governor | Sudan Tribune, September 2, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – Governor of Central Darfur State Mohamed Ahmed Jad al-Sid said the hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) would cut its presence in the state in October. The semi-official Sudan Media Center (…)

UNAMID completes construction of new base in Jebel Marra | Sudan Tribune, September 12, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – An aerial photo published by the hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) Wednesday has shown completion of the Mission’s base in Golo, Jebel Marra area, Central Darfur State. Last year, the UN (…)

UNAMID to withdraw from 4 sites in North Darfur | Sudan Tribune, September 15, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – The government of North Darfur State said the hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) would withdraw from a number of sites in the state according to the exit strategy agreed among the Sudanese (…)

UNAMID to withdraw from two sites in West Darfur in November | Sudan Tribune, September 22, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – The hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) would hand over Morny and Mistry sites to West Darfur government next November, said West Darfur minister of urban planning Faisal Hassan Haroun The (…)

UNAMID sites in South Darfur to be turned into university colleges: governor | Sudan Tribune, October 3, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – Governor of South Darfur State Adam al-Faki on Wednesday visited premises of the hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) that would be handed over to his government at the end of the year as part of (…)

UNAMID hands over two additional sites in Darfur | Sudan Tribune, October 11, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – The hybrid peacekeeping operation known as UNAMID this week handed over two sites in North and South Darfur to the Sudanese authorities as part of its plan to finalize Mission’s reconfiguration process by (…)

UNAMID hands over two policing centres in South Darfur | Sudan Tribune, October 16, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – The hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) on Tuesday said it handed over two policing centres at IDPs camps to the Sudanese government as part of the exit strategy. “On 14 October 2018 UNAMID (…)

UNAMID hands over team site in East Darfur | Sudan Tribune, October 31, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – The hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) said it has withdrawn from a team site in East Darfur State. “On 30 October 2018, UNAMID officially handed over the Mission’s team site in Shaeria, East (…)

UNAMID to fully withdraw from South Darfur in January: official | Sudan Tribune, November 5, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – The Government of South Darfur said arrangements are underway to receive two sites from the hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) (…)

UNAMID hands over 4 team sites in Darfur | Sudan Tribune, November 11, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – The hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) has handed over four sites to the Sudanese government as part of the Mission’s exit strategy from the region. The Mission on November 1st has withdrawn (…)

UNAMID completes withdrawal from 10 sites in Darfur | Sudan Tribune, December 21, 2018 (KHARTOUM) – The hybrid peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID) Thursday said it has concluded the closure and handover of 10 team sites to the Sudanese government. In a press release on Thursday, the Mission (…)

A DETAILED ACCOUNT OF THE DATA UNDERLYING THIS REPORT

The data collected for the period January 2017 to April 2019 exists in three forms in the archive for this report: [1] compilations of dispatches and reports from this period for all five Darfur states; [2] data spreadsheets in which each violent event(s) is distilled into the tersest form: date of dispatch; date of event; location of event; nature of event; consequences of the violent event(s); perpetrators of violent event(s); ethnicity of victims of violence (if there is enough in a given dispatch to allow for an inference in this regard); the source, most often Radio Dabanga by virtue of its legion of reporting sources on the ground in Darfur; and finally [3] all data has been mapped quantitatively onto five maps of Darfur, one for each state.

The events in the five data spreadsheets have represented individually or grouped in units and then been “scaled” to a number from 1 – 25. In addition to simply tabulating the number of murders, rapes, and beatings, the scaling also reflects the amount of property damage (particularly to farms and crops), the threat to greater populations (e.g., denial of access to water), and other defining features of the violence. In short, every event is rendered quantitatively, if sometimes amalgamated with other events in the same area when there are an especially large number of events (e.g., Tawila locality, North Darfur, Gireida and Nyala, South Darfur, and particularly the extremely violent Nierteti area of Central Darur). Some events require even larger numbers (50+): these tend to be large violent displacements of non-Arab/African populations and inter-Arab fighting in East Darfur. However imperfect the method of quantification may be, it has been deployed consistently.

This consistency is important when representing a total tabulation of violent events for various areas on the five discrete maps for the five Darfur states. On each map, overall violence is represented by circles of different sizes and colors; a key for understanding these circles is provided with each map. Because of visual constraints, even some cartographic uncertainty in the underlying dispatches, there is inevitably some approximation in the placement of the circles. Moreover, they are, as I’ve already noted, sometimes aggregations of data about violence in specific areas. But there can be little doubt about where violence has been concentrated for the past two years and more.

Because the statistical record is only very partial, the “scaling” technique employed should be understood as giving only a geographically relative indication of where violence has been concentrated and to what extent. It does not and cannot comprehensively represent violence in Darfur; we simply do not have the data. Moreover, geographic representation cannot do full justice to the voluminous data of these five compendious spreadsheets.

The most revealing way of assessing violence in Darfur, as represented in this report, would be to look at the spreadsheets with continual reference to detailed maps of Darfur (I have used a number of maps, but my primary source is the highly detailed five-part UN reference map collection of 2012 – 2013).

There are more than 800 data entry points in the five spreadsheets altogether. Moreover, a great deal of the data in the spreadsheets (particularly fires in displaced persons camps) cannot be easily rendered visually as “violence”; but levels of destructiveness have been indicated in the spreadsheets.

These concentrations of violence should be compared with the sequence of UNAMID withdrawals, past and future, indicated chronologically in Appendix A above.

THE DATA

West Darfur:

Compilation of dispatches, reports: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qw

Data spreadsheet: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2q7

Mapping of data: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2pZ

Central Darfur:

Compilation of dispatches, reports: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qx

Data spreadsheet: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qp

Mapping of data: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qr

North Darfur:

Compilation of dispatches, reports: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qJ

Data spreadsheet: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qF

Mapping of data: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qA

South Darfur:

Compilation of dispatches. reports: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qI

Data spreadsheet: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qh

Mapping of data: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qc

East Darfur:

Compilation of dispatches, reports: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2qu

Data spreadsheet: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2pS

Mapping of data: https://wp.me/p45rOG-2pW