“‘Changing the Demography’: Violent Expropriation and Destruction of Farmlands in Darfur, November 2014 – November 2015”

Eric Reeves, author | Maya Baca, research and editing | December 1, 2015 | http://wp.me/p45rOG-1P4

This final distillation of dispatches from Radio Dabanga takes a very lengthy and more radical form, explained in the narrative that follows. Using all data from the past year (November 1, 2014 – present), I have represented violent expropriation of African farmlands by Arab militias—primarily, but far from exclusively, the Rapid Support Forces—as fully as possible. Beyond the framing narrative below, I provide a timeline of significant events for the period in question, as well as a guide to Darfur’s geography, and critical individuals and organizations. There is also a brief bibliography, followed by examples of contrasts in the reporting of Darfur’s realities by Radio Dabanga and by the Khartoum regime. Since this project is almost entirely reliant on Radio Dabanga, this contrast is of some significance. [All elements of the report, except for the maps, are here].

The quantification here of violent land expropriation—increasingly by Arab groups from outside Sudan—is unprecedented. My hope is that the significance of the issue can be rendered clearly, revealing what an enormous obstacle to any meaningful Darfur peace process this expropriation of land has created—and continues to go unaddressed in any negotiating process. For a sense of scale, we should recall that on January 24, 2015 the UN Panel of Experts on Darfur reported: “The effects of this [indiscriminate bombing campaign] have resulted in 3,324 villages being destroyed in Darfur over the five-month period surveyed by the Darfur Regional Authority, from December 2013 to April 2014.” And this is far from a complete survey, and does not represent any of the time period covered in this report (November 1, 2014 – November 2015).

The most important element of this project is a data spreadsheet representing every relevant event for the past year (more than 500) is available here; in turn, these data are visually represented on three maps of Darfur:

(1) West Darfur (including “Central Darfur”)

(2) South Darfur (including “East Darfur”)

(3) North Darfur

All three are based on the July 2012 UN administrative map for Darfur; primary guidance on more smaller-scale cartographic issues is the 2005 UN OCHA’s collection of Darfur Atlases.

What follows is the framing narrative.

Introduction

The primary purpose of this framing narrative is to provide context for the accompanying data spreadsheet and map set, both of which give a sense of the tremendous scale of violent expropriation and destruction of farms and arable land by Khartoum-backed Arab militias in Darfur, the vast western region of Sudan. This expropriation has been continuous since the beginning of the conflict, and indeed had occurred on a smaller scale in earlier years. Massalit lands were targeted in particular during this early phase of expropriation. The primary source for data is, perforce, Radio Dabanga, which has done a truly remarkable job of providing current, accurate, and detailed accounts of what is occurring in Darfur. In journalistic style and standards, it has improved dramatically over the past six years, and is now without rival in providing us insight into Darfur’s realties. Without Radio Dabanga these realities, it is safe to say, would be known only—and only very partially—by those on the ground; Radio Dabanga represents a pioneering effort in journalism amidst ongoing genocide. It should also be said, however, that Human Rights Watch has issued two highly significant reports on Darfur over the past year, and the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has been the source of a great deal of data concerning humanitarian issues.

[Proper nouns, unusual nouns, dates, and some numerical figures in the text have been put in bold on first appearance; all emphases in bold within quoted materials have been added; unless otherwise indicated, all dispatches and reports are from Radio Dabanga. See here for an extensive compilation of names, places, terms, as well as humanitarian, diplomatic, and military actors.]

Time-frames

The time-frame for the narrative and data is November 1, 2014 to the present—a little over a year. November 1 is only a partially arbitrary terminus a quo, for it was also the date on which the 36 hours of brutal sexual violence in Tabit, North Darfur finally ended. By then more than 220 girls and women had been raped by regular Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) soldiers—on the orders of the local garrison commander (something the commander has admitted). International response subsequently is a tale of weak, cowardly, and dishonest posturing; only a February 11, 2015 report by Human Rights Watch, conducted on the basis of a remarkable series of interviews with victims and eyewitnesses, provides authoritative insight into the events at Tabit (see below).

Pain and anguish are everywhere in Darfur

The present report may cover only a year of violent land expropriation and destruction—destroyed in the sense that armed Arab militias and militant groups set crops ablaze or bombed fields or loose their cattle and camels on lands that had been planted, with crops approaching harvesting. A UN report giving a dynamic sense of the violence at mid-year 2015 may be found here. But it is a year that largely replicates what had occurred the year before, and essentially the year before that, mutatis mutandis. And again, violent expropriation of farmland, livestock, indeed all portable possessions of value has been a constant in the genocidal counter-insurgency campaign of Khartoum’s National Islamic Front/National Congress Party regime. Elements of the campaign could be discerned in the events of 2002, but the broader effort began in earnest following the successful April 2003 attack on the El Fasher (North Darfur) air base by the Sudan Liberation Army/Movement (SLA/M—at the time a relatively united force).

The enormous success of the attack (which included destroying military aircraft on the ground, abducting the base commander, and making off with large stocks of weapons, ammunition and vehicles) was an intolerable scandal in the eyes of the leading military figures in the regime, including then Minister of the Interior (General) Abdel Rahim Mohamed Hussein. (An arrest warrant has been issued for Hussein by the International Criminal Court for massive crimes against humanity; warrants for both massive crimes against humanity and multiple counts of genocide in Darfur have been issued for President Omar al-Bashir.) The Arab militias recruited by these men and others in the regime were composed substantially of northern abbala, or camel-herding, fighters, but a number of Arab tribal groups in the south and west contributed as well. They became internationally notorious as the Janjaweed.

The years 2003 – 2005 saw almost inconceivable levels of village looting and destruction, killings, rapes, and violence of all descriptions. But while this diminished in subsequent years—largely because the vast majority of non-Arab/African villages had been destroyed—it did not cease, despite efforts in some quarters to suggest otherwise. The consensus among my numerous informed Darfuri contacts—with regular access to information coming from Darfur—was that by the end of 2006 roughly 80 percent of all African villages had been destroyed, wholly or partially (for a variety of reasons, I prefer the designation African to non-Arab, if only because it is increasingly the means of self-identification by the people meant to be designated). I have chronicled in detail the violence that continued after 2006, both in my lengthy e-Book Compromising With Evil: An archival history of greater Sudan, 2007 – 2012 and in the archives of my website | http://sudanreeves.org/archive/. (For a thin but all too complete bibliography, see here.)

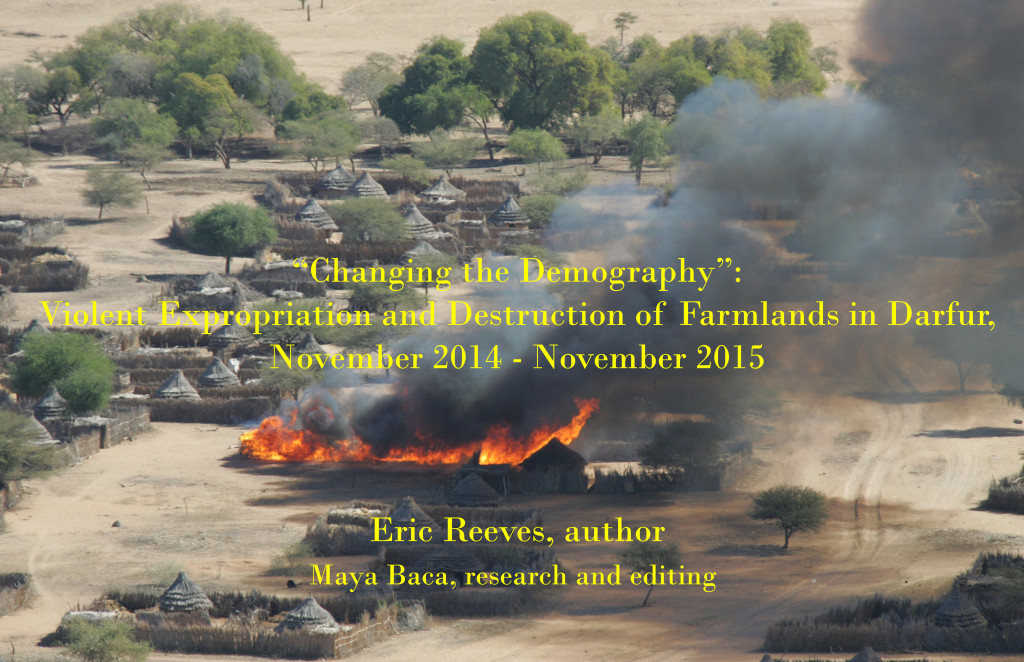

This scene from 2005 is being replicated with terrifying frequency at present; in North Darfur, the level of violence approximates to that of 2003 – 2005 (photograph by Brian Steidle)

What has been insufficiently recalled is how comprehensive the violent destruction of villages was, and how often it entailed destruction of the agricultural livelihoods of those whose villages had been attacked. Arab militia forces, especially in the early years of the genocide, worked hand-in-glove with the Khartoum regime’s Sudan Armed Forces when attacks were launched, very frequently early in the morning. Russian-built helicopter gunships and Antonov “bombers” would begin assaults on the village, rousing residents who were shot by Janjaweed and SAF forces when they left their homes—or forced to flee with nothing.

Khartoum relentlessly and deliberately bombs civilians and croplands in Darfur

Men and boys were the particular targets for killings; women and girls were more likely to be raped (and perhaps scarred or branded to ensure that the fact of rape could not be concealed). Destruction of villages entailed burning seed stocks and food stocks, the tearing up of irrigation systems, cutting down fruit trees, and—most destructively—poisoning wells with human or animal corpses. After all plundering of valuables was completed, the entire village would be torched. Once the village was destroyed, lands that had been planted with crops were often turned into foraging grounds for cattle and camels, further ensuring that food production would be impossible should villagers return.

Village destruction is extraordinarily comprehensive

We have had no relevant mortality data or data analysis since 2010. But by July 2010, data was sufficiently comprehensive to permit reasonable extrapolation to a figure for total mortality in excess of 500,000 human beings, dying directly from violence or the effects of violent displacement. For many fleeing their villages ended up dying of dehydration or lack of food because of the inauspicious direction in which they were forced to flee; many more died in camps that were insufficiently equipped to respond to the vast influx of displaced persons. There are now, according to the most recent report from the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, some 2.7 million internally displaced Darfuris, and this figure may well be low since only some of the displacement occurring over the past year is reflected in this figure; it also does not include those displaced living not in camps but instead with relatives, friends, and others in neighboring villages or even the larger towns of the Darfur region. Additionally, the most recent figure from the UN High Commission for Refugees puts the total number of Darfuri refugees in eastern Chad at 370,000—perhaps the most invisible of all large refugee populations in the world.

There have been two Darfur “peace agreements” signed over the past nine years—both disastrously conceived and falling apart rapidly without any positive impact on the level of violence. The Darfur Peace Agreement of 2006 (Abuja, Nigeria) succeeded mainly in dividing the rebel groups, since only one prominent rebel figure, Minni Minawi, signed the agreement. The rebel groups not associated with Minawi’s breakaway Sudan Liberation Army faction rejected the agreement, but were soon fighting among themselves; chances for a successful insurgency against the Khartoum regime were radically diminished.

In July 2011 a contrived, factitious group of “rebel leaders,” under the newly created name of the “Liberation and Justice Movement,” signed, along with the Khartoum regime, the “Doha Document for Peace in Darfur” (DDPD). Julie Flint, a keen observer of the Abuja negotiating process, on learning of how talks were conducted in Qatar, described them as “Abuja replayed as farce” (personal communication, March 22, 2011). And it has proved as much in the past four and a half years. The DDPD had no meaningful buy-in from Darfuri civil society, which has overwhelmingly rejected the Document. And for its part, Khartoum never abided by the terms of either the 2006 agreement or the 2011 agreement, and this was to be expected. The National Islamic Front/National Congress Party regime, which came to power by military coup in June 1989, has never abided by a single agreement made with any Sudanese party of actor—no one, not ever (for an extensive timeline of abrogated agreements, see here). Nor has the regime felt obliged to respect the “demands” of the UN Security Council. For example, when the Council belatedly recognized the role of Arab militias in the Darfur counter-insurgency campaign, it “demanded” of Khartoum in Resolution 1556 (July 2004) that the regime disarm and bring to justice the Janjaweed:

[Under Chapter 7 authority, the UN Security Council…]

- Demands that the Government of Sudan fulfill its commitments to disarm the Janjaweed militias and apprehend and bring to justice Janjaweed leaders and their associates who have incited and carried out human rights and international humanitarian law violations and other atrocities, and further requests the Secretary General to report in 30 days, and monthly thereafter, to the Council on the progress or lack thereof by the Government of Sudan on this matter and expresses its intention to consider further actions, including measures as provided for in Article 41 of the Charter of the United Nations on the Government of Sudan, in the event of non-compliance;

Khartoum’s response was contempt, and to the extent that it has responded to Janjaweed predations—often carried out in coordination with Khartoum’s regular ground and air forces—it has been by recycling Janjaweed militiamen into other paramilitary guises: the Popular Defense Forces (PDF), the Central Reserve Police (Abu Tira), the Border Intelligence Guards, and most recently the Rapid Support Forces, or RSF (al-Quwat al-Da’m al-Sari’ in Arabic).

A contingent of the fearsome Rapid Response Forces (RSF)

The latter are far better armed and equipped than the Janjaweed, and—significantly—enjoy the open support of all senior officials in the regime, including President al-Bashir. Khartoum never acknowledged the existence of the Janjaweed, even though the evidence of continuing military coordination between the SAF and various Janjaweed elements was consistent and overwhelming (see “Entrenching Impunity: Government Responsibility for International Crimes in Darfur,” Human Rights Watch, December 2005). Now, however, the RSF are celebrated as a key to “crushing the rebellions”—al-Bashir’s unfulfilled promise for the past three years, referring to popular military uprisings in not only Darfur, but also in South Kordofan and Blue Nile. Khartoum has also militarily annexed the contested Abyei region, which was denied a self-determination referendum in January 2011 and seized by Khartoum in May 2011.

[By far the most thorough and authoritative study of the RSF is contained in a report by Human Rights Watch: “‘Men With No Mercy”: Rapid Support Forces Attacks Against Civilians in Darfur, Sudan,” Human Rights Watch | September 9, 2015. Based on a great many interviews, including with those who had defected from the RSF and SAF, it is our best source other than Radio Dabanga in recording human rights abuses in Darfur; a distillation of the report may be found at | http://sudanreeves.org/2015/09/13/darfur-radio-dabanga-news-digest-number-24-13-september-2015/. Research was conducted between May 2014 and July 2015, and thus provides very considerable overlap with this narrative, although more broadly inclusive in its design, and less data-driven.]

Without fuller understanding of the character and extent of violent expropriation of farmland, and the violence that prevents farming and farm-related activities, the challenges to bring peace to Darfur simply cannot be understood. For the increasing pace and violence of land expropriation is made fully clear by the data assembled here; and this deadly acceleration shows no sign of diminishing.

The torching of villages is again a commonplace in Darfur

“Changing the Demography”: Forced returns of refugees and displaced persons

Returns of displaced persons from the camps in which they have lived, often for many years is a critical issue and something that the displaced greatly wish for—if there is adequate security. According to Radio Dabanga, 96.9 percent of those displaced worked in agriculture before they were displaced. More than anything, they wish to return to their lands and farms; but they will not do so when countless reports make clear the intensifying insecurity in the regions where their farms are located.

For its part, Khartoum has settled on a strategy for Darfur that rests on forcibly shutting down camps for displaced persons, doing so under the guise of “voluntary” returns, attempting to abuse the demographic and geographic ignorance of people desperate to return to their home and villages—or to new, “model” villages. Overwhelmingly, however, the people in the camps are all too aware of the new demographic realities—the continuing, relentlessly violent predations of Arab militias and the SAF—and refuse to leave what small bit of security is provided by the camps. That they chose to stay is telling: the camps for displaced persons in Darfur have what is now a long and gruesome history.

In 2004 a UN inter-agency investigating team found clear evidence that some of the camps for displaced persons had been turned into what were essentially “death camps.” The comparisons by seasoned relief workers, deeply shaken by what they found, were to Rwanda in 1994. Not coincidentally, in 2004 discussion began in Khartoum about compelling the returns of displaced persons in the camps, led by then-Minister of the Interior Abdel Rahmin Mohamed Hussein. This again became a central issue in 2010 in what would be billed by Khartoum as “The New Strategy for Darfur.”

The thinking by the regime has been that if the camps could be shut down, the rationale for an international humanitarian presence in Darfur would end. But security has never been great enough for people to return, and if some have succeeded, the vast majority have not. Camps themselves have been attacked frequently following the first major Janjaweed assault against displaced persons in Aro Sharow camp (West Darfur) in September 2005. These direct militia and military assaults on the camps have increased dramatically over the past decade, becoming more threatening and more violent. Overwhelmingly, Darfuris, both in Darfur and eastern Chad, reject returns as far too dangerous. News accounts of Darfur, except those from Radio Dabanga, are very rarely able to give voice to the views of Darfuris on this issue; this is also true of intimidated UN agencies, even as they are well aware of the importance Khartoum attaches to silencing these distressed and vulnerable voices.

But the realities of extreme insecurity cannot be wished away, nor will Darfuris be foolishly led to believe that a few “Potemkin villages” represent any fundamental shift in the attitude of the Khartoum regime. Several dispatches from Radio Dabanga make this eminently clear:

Displaced refuse to obey Darfur Authority and leave camps | July 31, 2015 | Zalingei, formerly West Darfur / El Geneina, West Darfur

Displaced people living in Central Darfur state have rejected the project for the voluntary return of the displaced population, set up by the Darfur Regional Authority. “None of the displaced people will return to their home villages, because of the lack of security.” The coordinator of the Central Darfur camps said that the people refuse the voluntary return offered by the Darfur Regional Authority (DRA), “because the reasons for their displacement still exist.” He stressed that weapons from the militias should be collected, and criminals should be prosecuted, prior for the mass return of the displaced people. “We need to survive first before having institutions and buildings.”

Despite the obvious cogency of the argument for security, pressure to return from the camps has been applied by other actors, including U.S. special envoy for Sudan Scott Gration during his disastrous two-year tenure (March 2009 – March 2011). He was taken to task by humanitarian actors who pointed out how little he knew about the implications of such returns. Gration also supported enthusiastically Khartoum’s “New Strategy for Darfur,” little more than a roadmap for ridding Darfur of international humanitarian actors, potential witnesses to what was occurring in Darfur. Of remaining relief workers in Darfur, 97 percent are Sudanese nationals and particularly vulnerable should they attempt to communicate what they have seen to the world outside Darfur, including the construction of “model villages”:

Central Darfur displaced reject model villages | August 27, 2015 | Ronga Tas, formerly West Darfur

The more than 30,000 residents of Ronga Tas camp for the displaced in Central Darfur’s Azum locality reject the moving of schools and health centres from the camp to model villages constructed by the Darfur Regional Authority. On Wednesday the coordinator of the Central Darfur camps told Radio Dabanga that the state government closed two basic schools, a secondary school and a health centre in the camp on Tuesday. “This is the first step towards the dismantling of the Ronga Tas camp which is part of the Darfur Regional Authority plans to force all displaced in Darfur to move to model villages it constructed with the financial support of Qatar,” he said. [The “Darfur Regional Authority” was a creation of the Doha Document for Peace in Darfur; under the leadership of Tijani Sese, the DRA has become riddled with corruption—ER]

Qatar is trying in effect to “buy” the “success” of the Doha Document for Peace in Darfur with its funding of “model villages.” This is well understood by Darfuris—only one of the reasons there is such deep distrust of Qataris as participants in a Darfur peace process.

Moreover, there have been a number of attempts to return displaced persons that have ended in catastrophe:

Militia kill nine, torch “voluntary return” village in South Darfur | December 14, 2014 | Gireida Locality, South Darfur

On Saturday, nine villagers were killed, and their homes burned to ashes in an attack by militiamen on Abu Jabra in Gireida locality, South Darfur. “About five weeks ago, the people of Abu Jabra had returned to their village, in the voluntary return programme organised by the Darfur Regional Authority,” an eyewitness from a neighbouring village told Radio Dabanga. “The formerly displaced had begun to settle themselves again at the place, located 20 km north of Gireida town.” “However, on Saturday afternoon, a large group of about 100 militiamen on camels and horses attacked the village, without any warning or clear reason. They fired at the people, killing nine instantly. After pillaging the entire village, they set it ablaze.”

In fact, there is a clear reason for the attack: the Arab militia forces have laid claim to the lands that are necessary for a village to thrive, indeed to survive at all. This was not only a murderous attack on people who had been led to believe that they really could begin life again, but a warning to others in camps throughout Darfur, making clear that despite Khartoum’s rhetoric, the militias that wield so much power in Darfur were determined that current land dispensations would not be challenged by returns. Surveying over 3 million internally displaced persons and refugees, these militias are prepared to use extreme violence to ensure that trends toward returns will not be allowed, whatever the regime in Khartoum may wish.

We should remember that there is a continual “referendum” on security in Darfur, conducted every day by the 370,000 Darfuri refugees in eastern Chad: they adamantly refuse to return to their lands and their country because insecurity is simply too great. And camps in eastern Chad are in many ways even less well served than those in Darfur itself. In August 2015, the UN’s World Food Program announced that in 2016 there would be no funding for continuing the provision of food to the refugee populations in the twelve refugee camps running north to south along the Chad/Sudan border. This comes on top of what have already been severe cuts to daily rations.

Despite the privation and extreme difficulty of life in eastern Chad, the refugees stay—and each day that they stay represents a collective judgment that as bad as life may be in Chad, the violent insecurity in Darfur is worse:

Refugees in eastern Chad refuse to return to Darfur | November 1, 2015 | Eastern Chad

The Darfuri refugees in eastern Chad categorically refuse to join the voluntary repatriation programme in the current insecure climate. The refugees set the restoration of the rule of law, disarmament of the militias, prosecution of the perpetrators of war crimes, and compensation, as conditions for their voluntary return. A delegation of the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) and a representative of the Chadian government, held a meeting with refugee leaders in the Djabal camp on Tuesday concerning the voluntary repatriation programme, as agreed between the UNHCR and the Sudanese and Chadian authorities in September.

“They told us that a Sudanese delegation will visit the camps in November to prepare for the return of the refugees,” El Zein Mohamed Ahmed, Radio Dabanga correspondent in eastern Chad reported. “The refugee elders and sheikhs asserted their categorical rejection of the voluntary repatriation programme while the situation in most parts of Darfur is still extremely unsafe and insecure,” he said. “They told them the refugees will not welcome any delegation from the Khartoum regime, which is the main cause of their suffering.”

It will bear close watching in the coming weeks and months to see if pressure from the UN High Commission for Refugees or Chadian strongman Idriss Déby’s regime in N’Djamena is brought to bear to force returns. Such compelled repatriation clearly violates international humanitarian law.

The connection between violent land expropriation and the issue of returns is captured in miniature in a single Radio Dabanga dispatch, and reveals just how unwilling Khartoum is to take on the new Arab settlers of lands that have been violently expropriated from the displaced:

Kalma displaced reject South Darfur housing plans | September 30, 2015 | Kalma camp

The residents of Kalma camp, near Nyala, capital of South Darfur, denounced the state Governor’s announcement of housing projects for the displaced on Tuesday. Their places of origin have been taken over by new settlers. The Governor intends to house the displaced in other areas. Yagoub Mohamed Abdallah, the coordinator-general of the Darfur camps told Radio Dabanga that in a meeting between Kalma camp leaders and Governor Adam El Faki, the latter said his government is seeking to implement a housing project at the camp site, similar to the one planned in neighbouring Kass locality. “El Faki intends to grant the more than 160,000 displaced in Kalma camp about 3,000 residential plots in Kass and, after re-planning of the Kalma camp itself, around 10,000 plots at the camp site.”

“[Governor el Faki] said that we cannot return to our areas of origin, as new migrant groups have settled there. This is unacceptable of course.”

The victims of the Darfur genocide and Khartoum’s effort to “change the demography of Darfur” will not yield to such misleading blandishments. They want their own lands back, and cannot be made to understand why Arab militiamen—some from Chad, Niger, even Mali—have been allowed to settle on those lands. The weakness of Khartoum’s “New Strategy for Darfur” (“model villages” representing “development,” as opposed to humanitarian responses to acute needs, justifying an international presence) could not be clearer. One way of understanding the upsurge of attacks on camps for the displaced—by both militia and regular military and security forces—is as a reflection of the regime’s belief that it can terrify weary residents, suffering from years of privation, into fleeing to these “Potemkin villages.”

The recent past

Despite poor reporting from international news organizations about Darfur, it is clear that following the signing of the Doha Document for Peace in Darfur—after a short hiatus for appearance’s sake—genocidal counter-insurgency began to accelerate again in early 2012. For almost four years, violence has escalated, as suggested by various individual archival entries for 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015 from www.sudanreeves.org. The past two years have seen extraordinary levels of violence, rivaling the destruction in the early years of the genocide. A timeline of events for the past year appears here. The militia and regular military forces have continued to sweep across all regions of Darfur, but have come over the past two years to concentrate on North Darfur, and in particular that area of North Darfur known as “East Jebel Marra”—east of the Jebel Marra massif and west of El Fasher, capital of North Darfur.

Tawila and Kutum have been the epicenters for the destruction in East Jebel Marra (EJM), both because there are relatively rich agricultural lands and because the region is a stronghold of the Fur tribe—the largest African ethnic group in Darfur (“Dar Fur” means something like “homeland of the Fur”). The Sudan Liberation Army faction of Abdel Wahid al-Nur is strong in Jebel Marra and parts of EJM, and Khartoum calculates that by destroying the Fur civilian base of support for al-Nur, they will gradually bring his forces to their knees. In short, what we are witnessing is an effort to further the enterprise first articulated in a memorandum from the Misterhiya, North Darfur headquarters of Musal Hilal, the most notorious of the Janjaweed leaders and identified by numerous witnesses as being present as commander in some of the very worst atrocities in the early years of violence. Dated August 2004, the memorandum has a chillingly clear central exhortation: “Change the demography of Darfur; empty it of African tribes.”

Musa Hilal

“Changing the demography of Darfur” in recent years has meant primarily the violent expropriation of farmlands from African farmers. This expropriation is also violently enforced, should farmers attempt to return to their lands, even from relatively nearby camps for displaced persons. Women and girls leaving to work on farms have been subject to an onslaught of sexual violence, long evident and still epidemic in nature. Men and boys are more likely to be killed, or simply badly beaten if they are lucky. Camels, the primary livestock of northern militia elements, are turned loose in huge numbers on lands where crops have been planted and are in various stages of maturation.

The ethnic animus in RSF and other militia’s violence is captured in an extraordinary passage from the Human Rights Watch report (“Men with No Mercy,” see above):

Ahmed, a 35-year-old officer in the Border Guards, spent two weeks at a military base in Guba [North Darfur] in December 2014 before being sent to fight rebels around Fanga. Two senior RSF officials, the commanding officer, Alnour Guba, and Col. Badre ab-Creash were present on the Guba base.

Ahmed said that a few days prior to leaving for East Jebel Marra, Sudanese Vice President Hassabo Mohammed Abdel Rahman directly addressed several hundred army and RSF soldiers:

“Hassabo told us to clear the area east of Jebel Marra. To kill any male. He said we want to clear the area of insects… He said East Jebel Marra is the kingdom of the rebels. We don’t want anyone there to be alive.”

Skepticism about whether genocide continues in Darfur would seem to be incinerated by such reports; moreover, the reference to the African rebel groups as “insects” has terribly ominous echoes of Rwanda.

Vice President Hassabo Mohammed Abdel Rahman

The RSF and other militia and paramilitary forces have declared ownership of the lands they have cleared on behalf of the Khartoum regime, and therein lies the greatest obstacle to peace in Darfur. Unless this pattern is changed decisively, and expropriated agricultural lands restored to their rightful owners, peace cannot come to Darfur. Those who have lost their lands will never accept a peace in which they are required to sacrifice their major livelihood asset; failure to address this issue realistically was the major flaw in both the Darfur Peace Agreement and the Doha Document for Peace in Darfur. The latter—which has provided a diplomatic excuse for inaction on the part of many Western countries, including the U.S.—has now been dismissed as unworkable and useless by all good faith actors, again including the U.S. Only Khartoum cleaves to the Doha agreement as a means of avoiding true mediation of the 12-year-old conflict.

But there is a terrible obverse to the problem of restoring lands to the displaced African farming communities, again now numbering more than 2.7 million internally displaced persons along with 370,000 Darfuri refugees in eastern Chad. For the various Arab militias—including some authoritatively reported to be from Chad, Niger, and Mali—will not willingly give up land they now see as theirs. This, they believe, is their reward for the genocidal counter-insurgency effort that has been directed primarily against African farmers in rural villages and areas, and increasingly in the camps and their immediate environs.

Newly displaced persons near the Chad/Darfur border; refugees in eastern Chad refuse to return to a violence-torn Darfur

Certainly these violent expropriations and control of farmlands have occurred with the clear approval of Khartoum, however chaotic the violence becomes at times (militia groups fighting one another, or even attacking local police and the SAF itself). But there can be no peace without a restoration of African farmlands, even if that restoration cannot be complete: Khartoum’s sanctioning of Arab efforts to seize lands and use them as pasturage for their livestock has created a situation the regime will find increasingly difficult to reverse, had it the will to do so. Any attempt by Khartoum to induce the Arab militias to give up the lands they have violently claimed would produce a violent backlash, and involve the regime in a new war—this time against Arab groups as well as the present, largely African rebel groups.

This issue points to the primary obstacle to a real peace in Darfur, and yet there is no international discussion of this issue. It has not figured in meaningful ways in either the Darfur Peace Agreement or the Doha Document for Peace in Darfur. And in December of last year, the incompetent and perversely ambitious Thabo Mbeki and his so-called African Union High-Level Implementation Panel suspended Darfur peace mediation efforts. There is presently no momentum behind any talks, merely vague discussion of possible mediation by Gulf states (this despite the fact that the Qataris are deeply mistrusted by Darfuris after their complicity in the Doha agreement, as are Arab actors in general, having acquiesced in Darfur’s destruction for so many years).

But violence in Darfur continues at a shocking level (see my most recent Darfur News Digest, November 6, 2015, which includes links to all previous reports). We have continual reports of rape, murder, beatings, and kidnappings as a means of extortion—and most significantly, violent expropriation of farmlands and violence used as a means of keeping farmers from returning to or working on these lands. The destruction of crops by livestock let loose to forage has been especially intense this harvest season.

Prospects

In short, the situation in Darfur is not static; it is getting worse, a great deal worse. The present security force in the region, the UN/African Union “hybrid” Mission in Darfur (UNAMID), has been a dismaying failure, and is slowly being drawn down by the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations under Hervé Ladsous. A force originally mandated to include over 25,000 personnel will soon have only about 15,000 and Khartoum is pushing hard for further reductions—indeed, for an “exit strategy” from all of Darfur. West Darfur came very close to being sacrificed in the June 2015 UN Security Council renewal (UNAMID would have been required to pull all its personnel from this area of Darfur). And yet any survey of violence over the past year reveals a tremendous amount has occurred in West Darfur—and much more if we recall that “Central Darfur” is an artificial geographical cut-out from West Darfur by the Khartoum regime, created entirely for political purposes.

The incompetence, corruption, and dishonesty of UNAMID have been repeatedly exposed, particularly in the leadership of Rodolphe Adada (Congo), Ibrahim Gambari (Nigeria), and Mohamed Ibn Chambas (Ghana). Urgent pleas from victims of ongoing atrocity crimes go unheeded, protection provided by the force is minimal for a mission of this size. Khartoum repeatedly denies access to UNAMID, even into camps for displaced persons, grounds UNAMID aircraft, and on at least one occasion denied the medical evacuation of a critically injured peacekeeper, who later died of his wounds. Unsurprisingly, suffering from poor morale, UNAMID makes fewer and fewer forays into dangerous areas, and reporting on events is inevitably dismal, indeed largely worthless. In trying to understand the context for UNAMID failures, however, we should bear in mind that Khartoum-backed Arab militias are clearly responsible for a majority of the most serious and deadly armed attacks on UNAMID patrols and convoys. The evidence in aggregate is overwhelming, and yet no international actor of consequences will say as much.

Radio Dabanga versus UNAMID as a reporting authority on events in Darfur

We catch clear sight of the reason for using the dispatches of Radio Dabanga, upon which this report is essentially based (as opposed to the terse and uninformative UNAMID reports), in surveying UNAMID’s response to the mass rapes at Tabit, North Darfur. For 36 hours, from October 31 into November 1, 2014, regular Sudan Armed Forces troops, on orders from their garrison commander, brutally raped more than 220 girls and women in Tabit, and severely beat many men. The first report of the nature of the events at Tabit came from Radio Dabanga in a November 2, 2014 dispatch, accurate to an astonishing degree given the chaos that followed such a terrifying event. Virtually all in the dispatch was confirmed by an extraordinary report from Human Rights Watch (“Mass Rape in North Darfur,” February 11, 2015), using the evidence gathered so diligently and effectively by lead researcher Jonathan Loeb.

What was UNAMID’s response to reports of the events at Tabit, easily accessible by road from a nearby UNAMID post? A team of investigators was allowed in only after eight days (November 9) had passed, giving Khartoum and the SAF, along with Military Intelligence, ample time to sanitize the crime scene and terrify into silence all potential witnesses. The security presence during the UNAMID investigation was overwhelming and highly intimidating, and everything that occurred during the investigation was conspicuously recorded. On the basis of interviews conducted in this environment, UNAMID nonetheless published a very short report (November 10) declaring it “found no evidence of mass rapes.” Shortly thereafter, however, an internal UNAMID report on the investigation was leaked to me, making clear that UNAMID was well aware of the impossibility of their conducting a meaningful investigation in the circumstances that prevailed.

But having allowed one UNAMID mission to investigate Tabit, however badly, Khartoum refused to allow a subsequent UNAMID mission, and has denied all subsequent international calls, including from the UN, the EU, and the U.S., for an independent investigation. But no real pressure was applied on Khartoum, and predictably, the regime offered no opportunity for further investigation. It did close down UNAMID’s human rights office in Khartoum (November 25, 2015); it did expel two senior UN humanitarian officials the following month; and it has become much more emphatic in its demands for UNAMID to withdraw entirely. Supported unstintingly by Russia on the Security Council, even on the matter of investigating events at Tabit, Khartoum will likely prevail in reducing further the mandate and makeup of UNAMID when it comes up for renewal in June 2016.

To this day, Khartoum denies anything occurred at Tabit, denies all charges of rape by SAF soldiers, and upbraids the international community for fabricating a story meant to discredit the regime. This is despite the fact noted above and first reported by Radio Dabanga that the garrison commander admitted the rapes occurred.

Khartoum’s ambitions

Instead of searching for a viable peace process, al-Bashir and his generals remain committed to military success that entails “crushing the rebellion,” and the army is currently preparing for yet another dry season offensive in South Kordofan and Blue Nile. Aerial attacks on civilian and humanitarian targets have long been a constant in both regions as a means of collapsing the agricultural economy and terrifying people into fleeing; the very same strategy has long been deployed in Darfur, and gives all signs of continuing with brutal regularity and complete lack of discrimination between military targets and civilians. Such attacks are war crimes, and in aggregate constitute crimes against humanity under the Rome Treaty that is the statutory basis for the International Criminal Court (see pages 19 – 20 of “‘They Bombed Everything that Moved”: Aerial military attacks on civilians and humanitarians in Sudan, 1999 – 2012”).

Unless the international community puts serious pressure on Khartoum to halt these war crimes, they will continue indefinitely. The same is true of violent land expropriation in Darfur, particularly North Darfur. There are no signs that the problem is well understood by recent negotiators, including Mbeki, and no signs that the international community intends to pressure Khartoum to halt attacks that make peace increasingly difficult.

Khartoum has been enormously successful in turning Darfur into a “black box” from which very little information is allowed to flow to the outside world. The vast range of contacts that provide Radio Dabanga with its ability to report so fully is quite unique, indeed represents something unprecedented on the part of people in the very midst of ongoing genocidal destruction. But by excluding journalists—except on rare, heavily controlled visits to particular locations—and by keeping all human rights reporters out of Darfur, the regime has succeeded in obscuring almost entirely a region that once had broad international advocacy support in its bid to escape tyranny and violence. And even as this “black box” has been created, there have been energetic efforts to re-write the Darfur narrative, some extraordinarily perverse.

The UN humanitarian agencies, for their part, have been almost completely intimidated by the regime and release very little of the information they possess by virtue of their presence in Darfur. Rigid self-censorship became the norm under perversely accommodating former UN head of mission Georg Charpentier; and this in turn imposed the same obligation of silence on international nongovernmental humanitarian organizations (INGOs), thirteen of which were expelled at a stroke in early March 2009. UN officials at the time estimated that the effect of the expulsions was to reduce humanitarian capacity in Darfur by approximately 50 percent. Altogether, more than 30 INGOs have been expelled from Darfur, or forced by insecurity or lack of funding to halt operations. None of those INGOs remaining dare to go beyond what the UN says in speaking about Darfur’s horrific realities.

It is hardly surprising that Khartoum has worked very hard to shut down Radio Dabanga (based in The Netherlands), block its signal, and do whatever it can with alternative broadcast sources in an effort to reduce the huge following Radio Dabanga has in its radio broadcasts and web-distributed dispatches. In July of this year the Arab Satellite Communication Organization yielded to Khartoum’s demand that it end broadcasting Radio Dabanga.

Data on violent expropriation and destruction of farmlands in Darfur

While the data represented in the spreadsheet (more than 500 discrete entries) and three maps focus specifically on violent land expropriation and the violence that prevents farmers from working their lands, this is only part of the story of violence in Darfur. But the issue is critical, as I’ve stressed, and must be placed squarely at the center of negotiations before there is any chance of a peaceful resolution to the fighting. The international community has done a terrible job to date in recognizing the problem and its centrality to the peace that is so widely sought in the abstract.

The Khartoum regime appears far from prepared to accept land issues as a serious matter under the auspices of the Doha agreement to which it cleaves ferociously. It is almost certain that regime change will be necessary before meaningful negotiations can begin. Meanwhile, Darfur drifts further and further into a violent chaos in which the most basic human needs are not met. At the same time, the degree of insecurity prevailing on the ground may oblige all remaining relief organizations to withdraw. If this includes UN agencies such as the World Food Program and World Health Organization, massive mortality will surely ensue.

The stakes for millions of human beings are very, very high. The international community seems content with a vague grasp of realities on the ground, and has yet to see the import of data such as those collected in this report.