A Massive Catastrophe Looming in Darfur: Forcing displaced persons from camps in Darfur is a prelude to camp dismantling

Eric Reeves | January 5, 2016 | http://wp.me/p45rOG-1Qo

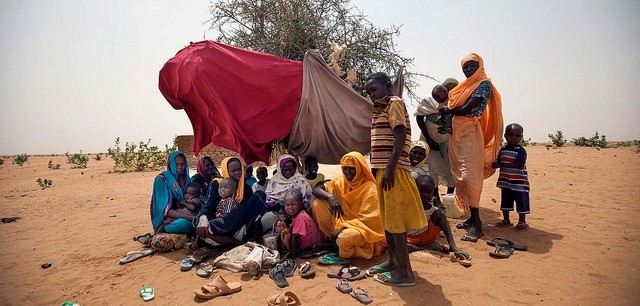

Recent statements from the Khartoum regime’s Second Vice-President, Hasabo Mohamed Abdelrahman, suggest that the National Islamic Front/National Congress Party is in fact moving more aggressively toward its long-announced plans to shut down and dismantle the camps for displaced persons in Darfur, a move that will have catastrophic consequences for these highly vulnerable populations, many of which are badly weakened by years of compromised humanitarian services and the fact of recent displacement. Outside the camps they will confront a vast, chaotic, immensely destructive maelstrom of violence, chiefly that orchestrated by Khartoum’s regular Sudan Armed Forces and the regime’s primary Arab militia ally, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF):

In a speech delivered before the representatives of former rebel groups and IDPs in El-Fasher, North Darfur on Monday, [Second Vice-President Hasabo Mohamed Abdelrahman] said Darfur has “completely recovered from the war and is now looking forward to achieve a full peace, stability and development.”

“IDP camps represent a significant and unfortunate loss of dignity and rights of citizens in their country” he said and called on the displaced “to choose within no more than a month between resettlement or return to their original areas.”

He further reiterated his government’s commitment to take all the measures and do the needful to achieve this goal, stressing that “the year 2016 will see the end of displacement in Darfur.” Abdel Rahman told the meeting that he has just ended a visit to Karnoi and Tina areas in North Darfur, adding the two areas which were affected by the conflict have totally recovered. He said his visit with a big delegation to the two areas “is a message sceptics in the fact that security and stability are back in Darfur”… (Sudan Tribune, December 28, 2015 | El Fasher, North Darfur) [all emphases in all quotes have been added—ER]

“Darfur has completely recovered from the war…” Second Vice-President Hasabo Mohamed Abdelrahman (photograph of militia fighters is from November 2015)

Radio Dabanga also reported on this highly significant, if utterly mendacious pronouncement:

Sudan’s Second Vice-President, Hasabo Mohamed Abdelrahman, said that his government is determined to close the camps for displaced people in Darfur next year [i.e., 2016—ER].

According to Sudan Tribune, the Second Vice President said Darfur has “completely recovered from the war and is now looking forward to achieve a full peace, stability and development.”

“The camps represent a significant and unfortunate loss of dignity and rights of citizens in their country,” he said, and called on the displaced people “to choose within no more than a month between resettlement or return to their original areas.” (Radio Dabanga, December 29, 2015 | Um Baru, North Darfur [“Vice President: Sudan determined to close Darfur camps”)

The Khartoum regime’s Second Vice-President, Hasabo Mohamed Abdelrahman—point-man in the dismantling camps for displaced persons in Darfur

The international community should hear Hasabo’s words with the greatest concern, particularly in his speaking of his “government’s commitment to take all the measures and do the needful to achieve this goal” of compulsory “repatriation.” The consequences of what will ultimately be forced expulsions from camps will be tremendous increases in violence, and mortality related to violence, a fact of which Darfuris are well aware. The response from the camps to Hasabo’s comments was predictable:

The Darfur Displaced and Refugees Association described the plans to dismantle the camps as “a major risk” and a violation of international humanitarian laws and human rights charters. Hussein Abu Sharati, the spokesman for the Association, told Radio Dabanga that there are no sufficient justifications for the dismantling of the camps.

“If the government would have realised a comprehensive peace in Darfur and Sudan, the displaced would have returned to their villages already – with the support from humanitarian organisations,” he said. “But we are still living in a war-like situation, with almost daily attacks by militiamen who kill, plunder, and rape with complete impunity.”

“The current situation in Darfur is much too dangerous for any return,” Abu Sharati added. “The entire region has been handed to militias. If the government cannot protect themselves in Darfur, how can it protect the people returning to their places of origin?” He stressed that the displaced would very much want to return, “yet only after the militiamen have been disarmed, and a secure and stable situation has been realised.”

These comments would take the same form in any of the IDP camps in Darfur. To the duplicitous inducement offered by Khartoum officials—offering to provide displaced persons with new, “model villages”—the response has also been unambiguous:

The residents of villages in the area of Aro in Wadi Azum locality, Central Darfur, took to the streets on Tuesday in protest against the construction of a model village in the area. The coordinator of Central Darfur camps for the displaced reported that the demonstrators moved to the Aro Basic School, chanting slogans against the commissioner of the locality, who was holding a speech at the school. The police responded by firing into the air to disperse the crowd. The shooting ignited fire at three school classes…

The Qatari government planned to fund the construction of water wells in 11 Darfur localities, as well as 10 model villages at a total cost of $70 million… [The Qataris are here simply attempting to “buy” the success of their ill-conceived, ill-fated, and diplomatically disastrous “Doha Document for Peace in Darfur” (see below) for which they provided auspices; there is no consideration of the security needs of displaced persons—ER]

The Darfur displaced reject their relocation to model villages as they consider the situation in the conflict-torn western region far from secure enough to leave the camps. Radio Dabanga, December 31, 2015 | Wadi Azum, (Central)/West Darfur [“Central Darfur villagers reject model village”]

Even more emphatic were these words from North Darfur, where violence is greatest:

The reactions of the displaced have continued to escalate following the announcement by the Second Vice President, Second Vice-President Hassabo Abdelrahman, that all camps will be dismantled in 2016. The displaced of the camps in Darfur have demanded the causes of the problems be solved first, before agreeing to the government’s option of dismantling the camps.

Omda Ahmed Ateem, coordinator of North Darfur camps, told Radio Dabanga that “now is not the time for the government’s option of dismantling the camp.” He said “the regime has committed crimes of genocide and ethnic cleansing. It must be removed first.” He asserts that all the camps are under the responsibility of the UN. “The UN has a right to act and not the government…”

The displaced of Central/(formerly West) Darfur camps have also refused the government’s plans of re-planning and voluntary return. The Coordinator of the Central Darfur camps told Radio Dabanga that the process of dismantling the camps is the government’s declaration of war and genocide again through starvation and forced displacement. He said the villages from which they have been displaced are now occupied by new [Arab] settlers.

He asserted that “the government’s move to dismantle the camps should be seen in the context of transferring the ownership of the displaced people’s lands to the new settlers.” (Radio Dabanga, January 1, 2016 | North Darfur [“Anger Escalates Over Sudan’s Plans to Dismantle Camps”])

That the international community fails to hear these assessments from Darfuris—or to understand the implications of Hasabo’s words, or to take seriously Khartoum’s plans—only encourages the regime to proceed. Hasabo’s comments were, as such comments typically are, a test of the international response; and so far the world has failed miserably in responding to the immense dangers reflected in Khartoum’s newly energized ambitions—or to the character of those announcing these ambitions.

In its singularly important report on the current violence in Darfur, Human Rights Watch reported (September 2015) on the character of the Rapid Support Forces, now the primary militia force deployed by Khartoum in Darfur, working in concert with the regular Sudan Armed Forces (SAF). One moment in particular stands out in this report. According to a defecting militiaman—speaking with the lead Human Right Watch investigator—in December 2014, the same Second Vice President, Hassabo Mohammed Abdel Rahman, exhorted SAF regular troops and RSF militiamen in North Darfur in the following terms:

“Hassabo told us to clear the area east of Jebel Marra…to kill any male.”

“He said East Jebel Marra is the kingdom of the rebels.”

“We don’t want anyone there to be alive.”

“He said we want to clear the area of insects…”

Darfur’s “insects”

This is the real face of Vice President Hasabo, and the Khartoum regime as a whole. We are currently witnessing a reprise of the brutally destructive dry season offensives of the past three years, offensives animated by the views expressed here by Hasabo—words he was evidently confident would never be published in any venue.

What Hasabo’s words about displaced persons really mean

We must make no mistake here: forced expulsions, by one means or another, are what Hasabo is speaking about. The project in its simplest and least persuasive form was first announced early in the genocide, when violence was at its most extreme. In the summer of 2004, just as humanitarian capacity was ramping up quickly and displacement was exploding throughout Darfur, plans for returns were being considered, and senior regime officials spoke publicly of returns as being in “full swing”—a crude effort at making something so by declaring it so. Abdel Rahim Mohamed Hussein, then Minister of the Interior and the regime’s special representative on Darfur, announced on Sudanese government-controlled radio on July 9, 2004 “that 86 percent of the Internally Displaced Persons had already returned to their villages.” Hussein further declared that “it was ‘most important’ to get people to return to their villages” [In fact, thousands of which had already been destroyed—ER]. Each state—the Darfur region has three—had its own plan of return” (UN Integrated Regional Information Networks, July 12, 2004). [An arrest warrant for Hussein has been issued by the International Criminal Court, charging him with massive crimes against humanity in Darfur—ER]

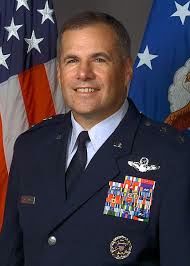

In 2010 Khartoum announced a “New Strategy for Darfur,” little more than a means of compelling further withdrawal by humanitarian organizations, since humanitarian needs were declared to be no longer compelling—a vicious example of regime mendacity (see “Accommodating Genocide: International Response to Khartoum’s ‘New Strategy for Darfur,’” Dissent Magazine (on-line), October 8, 2010). Disgracefully, this cynical initiative enjoyed the enthusiastic support of the incompetent U.S. special envoy for Sudan, Scott Gration, the equally incompetent AU negotiator in failed peace talks for Darfur, former South African president Thabo Mbeki, and Ibrahim Gambari of Nigeria, head of the AU/UN “hybrid” Mission in Darfur (UNAMID).

Such perverse support was not entirely unexpected, given Gration’s earlier shocking pronouncements concerning the issue of returns by displaced persons. Indeed, so shocking were Gration’s words in summer 2009 that he was confronted by a “humanitarian inter-agency management group,” which released harshly critical minutes of their meeting, all of which worked to reveal Gration’s profound ignorance of the crisis he was speaking about in such glib terms (see Washington Post, August 5, 2009). The same response to Gration’s assessments came from Darfuris themselves (see “U.S. Special Envoy on Returns of Displaced Persons in Darfur,” September 2009); additionally, Darfuris in exile also spoke harshly of Gration’s ignorance of the plight of IDPs (Sudan Tribune, September 13, 2009).

Scott Gration, the disastrous former special envoy for Sudan, appointed by President Obama despite a total lack of qualifications on Gration’s part; during his tenure he was immensely destructive of the chances for peace in Darfur

Presently, the expulsions Interior Minister Hussein was implicitly demanding in 2004 would force more than 2.5 million people into a vast arena of violence and extremely insecure conditions. The most recent report from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) indicates that there were, as of December 2014, 2.5 million people displaced in Darfur—and that 233,000 people were newly displaced in 2015 (Issue 52, December 21 – December 27, 2015). There is also a large population of displaced persons that does not appear in UN figures because they are inaccessible; many of these displaced are in remote areas of the Jebel Marra region, or remain simply uncounted in the chaos that continues to define Darfur. It is very likely that the populations in and around camps well exceeds 2.5 million—and this does not take into account the nearly 400,000 Darfuri refugees in eastern Chad.

Nor does the UN figure take into account the more than 500,000 Darfuris who have died from violence or the consequences of violence, now extending over 13 years. (The UN has offered no mortality estimate or update on its figure of 300,000 Darfuris dead from violence and its consequences since April 2008, nearly eight years ago.) This death toll represents a significant percentage of Darfur’s pre-conflict population.

The Experience of Darfuris “returning” to their lands and villages

The experiences of displaced persons attempting to return to their lands—even when nominally under the protection of the UN—have not been encouraging, despite some minor successes. Many incidents of the following sort have been reported, and word travels quickly in Darfur when the subject is the security of those returning:

[Seven] families who came back to the Guldo region [West Darfur] in the framework of the Sudanese Government’s voluntary repatriation initiative were found in an extremely worrying state. Witnesses told Radio Dabanga that they were part of 25 families who left Kalma Camp (South Darfur) as a part of the Voluntary Return program. However, the journey was too dangerous, and 18 families were forced to travel back to their original camp in South Darfur. Furthermore, they reported to Radio Dabanga that the remaining families did not receive any support from the province of West Darfur, even though it organized the deportation. They now call for international action to save these families, who are currently in a critical state. (Radio Dabanga | July 26, 2011)

More recently, Radio Dabanga reported (May 1, 2013):

Hundreds of displaced families who were returning to their areas of origin in South Darfur in connection with seasonal farming were forced to flee after large Misseriya [an Arab tribal group] crowds began arriving from different parts of the region. One of the farmers told Radio Dabanga on Wednesday that they are “concerned” with the presence of these groups settling in Shattai, “especially because there are so many of them and they are armed.” The farmers fear for “disastrous consequences if the Misseriya settle in their lands of origin.”

The claims to African farmland by Arab militiamen and thuggish opportunists present the greatest obstacle to peace in Darfur, and we have already seen all too fully what happens when men and women, girls and boys decide to leave the confines of camps, feeling that their only choice is to farm or starve. Many making these daring efforts to farm their lands, tend their cattle—or simply to gather wood, straw and clean water—are violently assaulted, killed, raped, or abducted. (See “‘Changing the Demography’: Violent Expropriation and Destruction of Farmlands in Darfur, November 2014 – November 2015,” December 3, 2015, which includes a data spreadsheet with more than 500 entries for this one-year period, all mapped onto three regional maps of Darfur.)

If we add to this present destructive dynamic the wholesale displacement of camp populations—literally forced out of the tenuous security of the camps, which also serve as focal points for the distribution of relief aid—a massive catastrophe will surely ensue. There may be efforts by the displaced to re-congregate in order to continue receiving international humanitarian relief. But Khartoum will most certainly not give access to INGOs in Darfur to work with these re-congregating populations of displaced persons.

Khartoum will be insistent on this point because it is key to the regime’s larger goal: remove the rationale for any continuing international presence in Darfur, including not only INGOs but also UNAMID. If the camps are shut, no matter what the forcibly expelled populations do, Khartoum will deny them as fully as possible humanitarian access. They are willing to accept considerable international criticism in order to complete what has long been a primary goal in the regime’s genocidal counter-insurgency war in Darfur.

KHARTOUM’S TOOLS FOR CAMP EXPULSIONS

• Attenuation of humanitarian capacity

Efforts to shut down the camps and compel “returns” have long extended to the deliberate diminishing of humanitarian capacity, both domestic and international. As Radio Dabanga recently reported in an all too representative dispatch:

The residents of the Otash camp for the displaced near Nyala, capital of South Darfur, have renewed their complaints about the shortage of drinking water. One of the Otash camp sheikhs told Radio Dabanga that the drinking water crisis started nearly one month ago after both the governmental Water and Sanitation Department (WES) and the organisation which used to provide fuel for the operation of the pump engines stopped their work at the camp “without providing a reason.” The sheikh appealed to the local and state authorities to speed up the provision of clean drinking water to the displaced. He pointed out that the camp residents lack the means to fetch water from the commercial wells. “They are now forced to buy a jerry can of water for SDG2 ($0.33).” (January 3, 2016 | Otash camp, South Darfur)

Lines for water in many camps can be extremely long and time-consuming; Khartoum is deliberately exacerbating the problem in some camps

Such efforts to make camp life increasingly unbearable have long been in evidence and are too numerous to catalog, but are now clearly escalating and are marked by greater coordination and targeting of critical resources.

At the same time, international nongovernmental humanitarian organizations (INGOs) continue their slow withdrawal from Darfur. Withdrawal of an INGO is typically quietly announced, with funding shortcomings most often given as the reason for suspending operations. And it is true that the international humanitarian community, governmental and nongovernmental, has developed a case of “compassion fatigue” when it comes to Darfur. There are notable, in some cases heroic exceptions—in individuals and in organizations. But in fact, insecurity is a primary consideration in virtually all withdrawals, along with Khartoum’s peremptory expulsions. Here we must recall that in March 2009 the regime expelled 13 of the world’s finest humanitarian organizations from Darfur, roughly half the humanitarian capacity in the region; other expulsions had preceded and many have followed. No remotely credible explanation was offered.

The most recent notable example is that of the UK’s Tearfund:

On Monday, government officials visited the offices of Tearfund across Sudan and ordered them closed until further notice…. “We are actively seeking the Government’s direction on how to proceed in order to resume our humanitarian activities.

“Tearfund project beneficiaries are our greatest concern at this time. Tearfund has been working in Darfur since 2004, and is currently delivering life-saving humanitarian assistance with a focus on nutrition, food security, water and sanitation,” the statement reads.

Radio Dabanga reported earlier this week that security agents raided the organisation’s office in Nierteti on Monday. “They seized all the materials, equipment, and devices, including more than SDG250,000 ($39,220) cash in the treasurer’s safe, and personal belongings of the staff members,” an eyewitness reported. “They then took the foreign and Sudanese staff to the office of the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) in Nierteti.” (Radio Dabanga “Sudan closes all Tearfund offices in the country,” Khartoum | December 17, 2015)

Such “asset stripping”—amounting to tens of millions of dollars stolen, extorted, and expropriated—was a signal feature of the massive expulsion of INGOs in March 2009. These monies and resources were as a consequence unavailable for other humanitarian crises around the world; instead of helping the most needy, money and resources belonging to humanitarian organizations slipped into the pockets of the kleptocrats who rule in Khartoum (see “Kleptocracy in Khartoum: Self-Enrichment by the National Islamic Front/National Congress Party, 2011 – 2015,” Eric Reeves/Enough Project Forum Report | http://www.enoughproject.org/blogs/enough-forum-release-kleptocracy-khartoum/).

Intimidation is another way in which Khartoum compromises the work of INGOs, accusing them preposterously of alleged “crimes against the state” (this was the same pretext used for the March 2009 mass expulsions):

North Sudan’s secretary for the political sector threatened Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) operating in Kordofan and Darfur with penalties or expulsion on Monday [July 11]. Gudbi-Al Mahadi, of Sudan’s ruling National Congress Party (NCP), is reported by the pro-Khartoum Sudanese Media Centre as threatening NGOs with “legal penalties” and “halting of activities” as some were “found providing logistical support to insurgents.” No evidence was provided to support the allegations against the NGOs. But officials from the ruling party said they do not want a repeat in South Kordofan of the large humanitarian presence and the creation of camps for the displaced civilians, as has happened in Darfur. (Sudan Tribune, July 11, 2011)

This atmosphere of intimidation and threats, reported by a wide range of sources to me and to colleagues, was borne out in a report (January 2011) by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR). In an egregious example of UN mendacity from late 2010, Georg Charpentier, in his capacity as UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Sudan, declared that “UN humanitarian agencies are not confronted by pressure or interference from the Government of Sudan”—this in a written statement to the Institute for War and Peace Reporting. Such a claim was a patent lie. In a very extensive series of interviews with UN officials (obviously obliged to speak off the record for the most part, but not entirely), IWPR found that:

According to UN officials who spoke to IWPR, the Sudanese government is actively preventing UN agencies which operate on the ground from accessing information necessary for compiling much needed reports on the humanitarian situation in the region. (“UN Accused of Caving In to Khartoum Over Darfur: Agencies said to be reluctant to confront Sudanese government about obstructions to humanitarian aid effort” | January 7, 2011)

And further that,

UN and diplomatic sources who spoke to IWPR say Khartoum is deliberately undermining humanitarian efforts.

Charpentier’s statement—”UN humanitarian agencies are not confronted by pressure or interference from the Government of Sudan”—was a despicable lie, and confirmed as such not only by IWPR but by journalists in Khartoum who sharply questioned Charpentier about his comments and reports.

Georg Charpentier—destructively dishonest in his role as chief of UN humanitarian operations in Sudan

A substantial Tufts University study, surveying Darfur in 2010, gave us a far more accurate assessment of the situation in Darfur. The Tufts study (“Navigating Without a Compass: The Erosion of Humanitarianism in Darfur,” January 2011 Briefing Paper) makes abundantly clear that the UN and INGOs were largely flying blind in Darfur, and that this was a direct result of Khartoum’s restrictions on humanitarian assessment activity; critically, the humanitarian community did not have nearly enough data for issues like malnutrition. The context defined by the Tufts study should have been terrifying, even as it has only become more threatening in the intervening five years:

Crucial information about the humanitarian situation is lacking. There are serious issues with the proper validation of the nutrition survey reports and their immediate release—without such data neither the government nor the international community can properly understand the severity of the humanitarian situation or the efficacy of the response.”

… International humanitarian capacities have been seriously eroded and impaired to a point that leaves Darfuris in a more vulnerable position now than at any other time since the counterinsurgency operations and forced displacements in 2003 and early 2004. (“Navigating Without a Compass: The Erosion of Humanitarianism in Darfur”)

The Tufts report also noted that the limited data available reflected “an extremely poor nutritional situation with implications for functional outcomes of mortality and morbidity risk,” which puts in question UN accounts. People were becoming ill and dying because they did not have enough food to eat. The report notes as well “several causes for concern with regard to the reporting of humanitarian indicators,” especially in the context of “frequent claims [by the regime that] the situation is stable”:

The regular occurrence of emergency levels of Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) on a seasonal basis [ … ] are ignored by the international community. If the emergency benchmark of 15% is felt not to apply to Darfur, this needs to be properly explained and justified based on evidence.

The poor reporting by UNICEF on the available malnutrition estimates [ … ] buries GAM estimates by scattering them about within the report, thus making it harder for readers to evaluate.

This accusation by Tufts’ researchers was confirmed by the leak in 2014 of an unreleased UNICEF report on malnutrition in Sudan, including Darfur (see “An Internal UNICEF Malnutrition Report on Sudan and Darfur: Why have these data been withheld?” | September 5, 2014). There, in data withheld from international scrutiny, UNICEF reports shocking figures for GAM (Global Acute Malnutrition), here for children under five): Acute malnutrition rates for children in Sudan are among the highest in the world:

North Darfur: 28 percent acute malnutrition among children

South Darfur: 18 percent acute malnutrition among children

East Darfur: 15 percent acute malnutrition among children

Central Darfur: 13 percent acute malnutrition among children

West Darfur: 8 percent acute malnutrition among children

Many consider that a GAM rate of more than 10 percent among children under five to be the emergency threshold in a conflict zone. In North Darfur, the rate is almost three times this threshold.

“Chronic malnutrition [also known as “stunting”—ER] among children in Sudan:

Central Darfur: 45 percent

East Darfur: 40 percent

West Darfur: 35 percent

North Darfur: 35 percent

South Darfur: 26 percent

Such chronic malnutrition has seriously deleterious long-term consequences for both physical and cognitive development in children.

Why have these figures not been fully and widely promulgated by UNICEF, given its agency mandate? The Tufts study also gives a grim account of UN acquiescence before Khartoum’s obstructionism, and highlights the “reported blocking of the release of nutrition survey reports.” This directly contradicts claims by the UN’s Charpentier, and makes clear the viciousness of his mendacity.

[See Appendix A for a fuller account of UN misrepresentations of humanitarian realities in Darfur and the consequences of such misrepresentation; see also Humanitarian Conditions in Darfur: Relief Efforts Perilously Close to Collapse (in two parts) 16 August 2013 | Part 1 at http://wp.me/p45rOG-15l | Part 2 at http://wp.me/p45rOG-15f/]

• Violent Assaults on the Camps

If those in camps for the displaced do not voluntarily “return” to their lands and villages—if the are forced to “return” no matter how insecure their lands, no matter how fully expropriated by Arab militia forces—then Khartoum is clearly prepared to escalate further its assaults on these highly vulnerable camps, attacks that have been reported for over a decade. The first such attack reported in detail came from Ambassador Baba Gana Kingibe, Special Representative of the Chairperson of the AU Commission on Darfur and head of the predecessor to UNAMID, the AU Mission in Sudan (AMIS). Though militarily small and weak, AMIS sometimes spoke with a voice of condemnation that UNAMID has never been able to muster.

In fall 2005 Aro Sharow camp for internally displaced persons, in the Jebel Moon area of West Darfur, and Camp Rwanda near Tawila (North Darfur) were savagely attacked by the Janjaweed, with conspicuous complicity on the part of Khartoum’s regular military forces. Kingibe minced no words:

On 28 September 2005, just four days ago, some reportedly 400 Janjaweed Arab militia on camels and horseback went on the rampage in Aru Sharo, Acho and Gozmena villages in West Darfur. Our reports also indicate that the day previous, and indeed on the actual day of the attack, Government of Sudan helicopter gunships were observed overhead. This apparent coordinated land and air assault gives credence to the repeated claim by the rebel movements of collusion between the Government of Sudan forces and the Janjaweed/Arab militia. This incident, which was confirmed not only by our investigators but also by workers of humanitarian agencies and nongovernmental organizations in the area, took a heavy toll resulting in 32 people killed, 4 injured and 7 missing, and about 80 houses/shelters looted and set ablaze.

The following day, a clearly premeditated and well-rehearsed combined operation was carried out by the Government of Sudan military and police at approximately 11am in the town of Tawilla and its Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp in North Darfur. The Government of Sudan forces used approximately 41 trucks and 7 land cruisers in the operation which resulted in a number of deaths, massive displacement of civilians and the destruction of several houses in the surrounding areas as well as some tents in the IDP camps. Indeed, the remains of discharged explosive devices were found in the IDP camp. During the attack, thousands from the township and the IDP camp and many humanitarian workers were forced to seek refuge near the AU camp for personal safety and security. (Transcript of press conference by Ambassador Baba Gana Kingibe, Special Representative of the Chairperson of the AU Commission on Darfur, Khartoum, October 1, 2005)

The following year would see additional direct attacks on camps for displaced persons. On November 2, 2006 even the feckless Secretary-General Kofi Annan finally found an occasion to condemn Khartoum’s genocidal assaults:

The Secretary-General condemns the large-scale militia attacks in the Jebel Moon area of West Darfur on 29 and 30 October [2006]. The attacks on eight civilian settlements, including a camp harbouring some 3,500 internally displaced persons, caused scores of civilian deaths and forced thousands to flee the area. The Secretary-General is particularly distressed on hearing reports that 27 of those killed were children under the age of 12.” (UN News Service [New York], November 2, 2006)

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Louise Arbour, also issued a report on these attacks, indicating that:

7,000 people fled the area [of the attacks]. The report [by the Office of the UN High Commission for Human Rights], [was] based on eyewitness testimony and village lists collected by UN monitors in the region. [ … ] Several witnesses quoted by the United Nations described seeing cold-blooded killings of children when the attackers ransacked villages, including a woman whose four-year-old was pulled from her grasp and shot dead. “Four children escaped in a group and ran under a tree for protection. An attacker came and shot at them, killing one of the children,” a witness was quoted as saying.

“Another group of three children (five, seven and nine years-old) were running in line. The five-year old fell down and was shot dead,” the witness reportedly added. One of the attackers reportedly told a boy who pleaded with him: “If I let you go then you will grow up.” The boy was then shot, the report said.” (Agence France-Presse [Geneva], November 3, 2006)

[This paragraph is strong evidence of “genocidal intent”: the boy, clearly ethnically African, was killed by an Arab militiaman, who made clear his intent that this African boy not grow to be an African man; that the militiaman may have feared the boy would ultimately grow up become a military opponent is irrelevant to the question of “intent,” i.e., killing the boy because he was African was killing him “as such,” the key determinant in genocidal intent—ER]

Amnesty International provided a highly informed account of the desperate humanitarian situation that confronted survivors of these massacres, suggesting that the total number of casualties from Janjaweed attacks would grow dramatically (the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights reported the terrified flight of approximately 7,000 civilians in an area then beyond humanitarian reach):

Janjawid militias attacked eight villages and a camp of displaced people in the Jebel Moon area of West Darfur on 29 October [2006], leaving at least 67 men, women and children dead. Other Janjawid attacks, including killings and abductions, have taken place in other parts of Darfur. Local inhabitants say the Janjawid are gathering in Sawani and Goz Banat, areas close to Jebel Moon, apparently in preparation for further attacks. Amnesty International is concerned for the safety of civilians who have fled the area, and of other villagers in West and North Darfur States.

While these attacks were occurring in West Darfur, North Darfur was enduring similar assaults, and the vulnerabilities of the displaced were brought into high relief by Lydia Polgreen of the New York Times, speaking specifically about the ominously named “Camp Rwanda” near Tawila:

A year ago it was a collection of straw huts, hastily thrown together in the aftermath of battle, hard by the razor-wire edge of a small African Union peacekeeper base. Today it is a tangle of sewage-choked lanes snaking among thousands of squalid shacks, an endless sprawl that dwarfs the base at its heart. Pounding rainstorms gather fetid pools that swarm with mosquitoes and flies spreading death in their filthy wake. All but one of the aid groups working here have pulled out.

Many who live here say the camp is named for the Rwandan soldiers based here as monitors of a tattered cease-fire. But the camp’s sheiks say the name has a darker meaning, one that reveals their deepest fears.

“What happened in Rwanda, it will happen here,” said Sheik Abdullah Muhammad Ali, who fled here from a nearby village seeking the safety that he hoped the presence of about 200 African Union peacekeepers would bring. But the Sudanese government has asked the African Union to quit Darfur rather than hand over its mission to the United Nations. “If these soldiers leave,” Sheik Ali said, “we will all be slaughtered.” (September 10, 2006, Camp Rwanda, near Tawila, North Darfur)

[The sheikh was referring to the very small African Union force known as AMIS; the much larger, though fatally compromised UN/AU hybrid force would not officially deploy until January 1, 2008—ER]

Since then attacks have grown more frequent, more violent, more threatening. In 2008, in a co-authored piece in the Wall Street Journal, I offered an account of a brutal attack on Kalma camp in South Darfur, near Nyala—the largest IDP camp in Darfur, then and now:

At 6am on the morning of August 25 [2008], Kalma camp, home to 90,000 displaced Darfuris, was surrounded by Sudanese government forces. By 7 am, 60 heavily armed military vehicles had entered the camp, shooting and setting straw huts ablaze. Terrified civilians—who had previously fled their burning villages when they were attacked by this same government and its proxy killers the Janjaweed—hastily armed themselves with sticks, spears and knives. Of course, these were no match for machine guns and automatic weapons. By 9am, the worst of the brutal assault was over. The vehicles rolled out leaving scores dead and over 100 wounded. Most were women and children. (Wall Street Journal, September 6, 2008; co-authored by Mia Farrow, who at the time had recently returned from Darfur)

The attacks on camps have been relentless. Notably, in August 2014 Khartoum’s regular military forces mounted a major assault on El Salam camp, also in South Darfur—an attack of the sort that is particularly likely to become a means of compelling people to leave the camps:

“Military raid on South Darfur’s El Salam camp” | Radio Dabanga, 5 August 2014 (El Salam Camp, Bielel Locality, South Darfur)

A large military force stormed El Salam camp for the displaced in Bielel locality, South Darfur, on Tuesday morning [5 August 2014]. The army troops searched the camp and detained 26 displaced. “At 6:30am on Tuesday, army forces in about 100 armoured vehicles raided El Salam camp,” Hussein Abu Sharati, the spokesman for the Darfur Displaced and Refugees Association reported to Radio Dabanga on Tuesday afternoon. “The soldiers searched the camp, treating the displaced in a degrading and humiliating way. They assaulted the people, treating them as suspects, and detained 26 camp residents. The market was pillaged, and the personal belongings of many displaced disappeared.”

According to Abu Sharati, the search for criminals, motorcycles, vehicles without number plates, and weapons in the camp, was done “under the pretext of the new emergency measures issued by the Governor of South Darfur State.” “But in fact the main objectives of this attack is terrorising the camp population, and the dismantling of the camp.” “Searches in this way constitute a violation of international humanitarian laws. They attacked the camp, beat and robbed the displaced, and pillaged the market. We do not know how many people were wounded yet. We are still are checking them, and inventorying the items missing.”

On August 8, 2014, Radio Dabanga published a follow-up report on the attack on El Salam camp for displaced persons:

The displaced of Darfur hold the UN Security Council and UNAMID responsible for the military raid on El Salam camp for the displaced in South Darfur, at the beginning of this week. In a statement to Radio Dabanga, the coordinator of the South Darfur camps said the attack on the El Salam in Nyala is contrary to the rules of displacement and the United Nations. “It is the UN and UNAMID’s responsibility to protect the displaced. The camps are not havens for criminality; people enter these camps because of the ravages of war.”

The leader of El Salam camp, Sheikh Mahjoub Adam Tabaldiya, confirmed to Radio Dabanga that a combined force consisting of security services, the army, and the police stormed the camp with more than 150 military vehicles, led by Abdulrahman Gardud, Commissioner of Nyala locality. Sheikh Tabaldiya termed the raid a farce. “When they entered the camp, they told the elders that they were searching for alcohol and drugs, but they were really looking for vehicles belonging to the armed movements, and families of rebels.”

“The military force did not find anything, but arrested more than 75 people and took them to the military court in Nyala. As there was no proof against them, all but four were released.” Aaron Saleh, Jacob Abdul Rahman Abdullah, Mahmoud, and Saleh Abdullah are reportedly still in detention in Nyala. Tabaldiya said that during the raid, 23 displaced people received various injuries as a result of beating and whipping.

There are now constant reports of attacks on the camps, larger and smaller in scale: rapes of women and girls gathering firewood or water near the camps, murder, abduction for ransom, and destruction of markets within the camps. Most recently (January 4, 2016), Radio Dabanga reported on another attack against the people of El Salam camp, and again this kind of attack, along with sustained threats and intimidation, will likely be typical of the violent efforts to compel people to leave the camps:

The residents of El Salam camp for the displaced south of Nyala in South Darfur have been terrorised by militiamen for a week. “For seven days now, a group of militiamen enter the camp each day from 8 am until 6 pm, and terrorise the people with their firing into the air,” Sheikh Mahjoub Adam Tabaldiya told Radio Dabanga from the camp. “On Friday evening, they seized Anwar Tarboush and beat him severely,” he added. “The people are terrified.”

The camp sheikh appealed to “the South Darfur government, UNAMID, and all those responsible, to stop the Abbala [Arab camel-herding—ER] militias’ access to El Salam camp, or allow them to enter without weapons.” With more than 80,000 residents, El Salam camp can be considered one of the largest camps in Darfur. Murnei camp in West Darfur, Zamzam camp in North Darfur, and Kalma camp in South Darfur are the largest camps, hosting about 125,000, 150,000, and 160,000 displaced respectively.

Appendix 2 (below) provides a selection of Radio Dabanga dispatches from the past month representing the violence into which displaced persons would be forced if Khartoum has its way, and the words of Second Vice-President, Hasabo Mohamed Abdelrahman are put into action.

More particularly, I have recently published an extensive survey of the past year’s violent assaults on Darfuri farmers, their families, as well as the destruction and expropriation of farmlands (“‘Changing the Demography’: Violent Expropriation and Destruction of Farmlands in Darfur, November 2014 – November 2015,” December 3, 2015). Whether living in or outside the camps, African farmers are clearly at risk if they attempt to reclaim or cultivate their lands. Indeed, as the overview makes clear, there are many areas in Darfur where forced returns will amount to a death sentence.

Darfuri refugees in Eastern Chad

Khartoum’s efforts to compel the returns of displaced persons cannot directly include the twelve Darfuri refugee camps in eastern Chad (running north to south, the distance is over 500 miles). But evidence suggests that Khartoum is pressuring N’Djamena more insistently to force the Darfuri refugee population of eastern Chad back into war-torn Darfur. Such compulsory repatriation would be an egregious violation of International Humanitarian Law, and yet UN agencies have done nothing to ensure violations of IHL do not occur. Indeed, in 2015 the World Food Program (WFP) announced that there is no budget to provide food to these refugees in 2016 (these are people who have already had their daily rations cut drastically by WFP). This has created enormous pressure on refugees to return to Darfur, no matter how violent the region may be.

The population currently numbers 380,000 according to UNHCR, a significant uptick over the last three years, directly contradicting bizarrely inaccurate reporting by the New York Times in February 2012, suggesting that the refugee population was actually diminishing (indeed, revealing a broader ignorance, one photograph in the dispatch was given a caption declaring that “peace had broken out” in Darfur). In February 2012, according to the UN High Commission for Refugees, the refugee population in eastern Chad was 282,000—a number at once largely static, and revealing in its precision: this total came from came registration numbers, which often bear a very imperfect relationship to the total population present at a given time. The current refugee population is approximately 100,000 greater than when the New York Times dispatch from West Darfur was filed.

Complicity of the Darfur Regional Authority (DRA)

One of the worst features of the 2011 Qatari-sponsored “Doha Document for Peace in Darfur” (DDPD) was the creation of a Darfur Regional Authority (DRA), always completely under the control of the Khartoum regime. The signatories to the DDPD were in no way representative of Darfuri civil society, which has overwhelming rejected both the DDPD and the DRA. Indeed, the “signatories” were nothing more than a ginned-up collection of rebel fragments, with very little power on the ground in Darfur and no relationship with the main rebel groups essential to any meaningful peace. Those who cobbled together this useless entity known as the Liberation and Justice “Movement” (LJM) made strange bedfellows indeed: chief among them were U.S. special envoy Scott Gration, yet again revealing his profound ignorance of Sudan and the Khartoum regime, and the now-deceased Libyan strongman Muamar Gadhafi (Gadhafi once caused a stir by referring to the Darfur conflict as a “quarrel over a donkey.”)

Julie Flint, who had been a close observer of the 2005 – 2006 peace talks in Abuja (Nigeria), which issued in a failed Darfur peace agreement, has in conversation described to me the Doha peace process in Doha as “Abuja replayed as farce.” No observer with whom I have communicated has shared a view much at odds with Ms. Flint’s. Nonetheless, there can be no denying that the Doha agreement was consequential.

It first gave Khartoum diplomatic protection from any international push to negotiate a meaningful peace agreement, one with significant buy-in from Darfur civil society. The regime cleaves vigorously to the DDPD precisely because it serves as insulation from pressure from the international community, and is the basis for various absurd characterizations of the security situation in Darfur. And in fact, for far too long the international community, including the EU, the U.S., the African Union, and the UN, have pretended as though the DDPD had some chance of success. It never did, but arguing that it should be “given a chance” gave these significant actors an excuse for doing no more to bring an end to fighting that has done nothing but escalate since the signing of the DDPD in July 2011.

The head of the Darfur Regional Authority, El Tigani Sese, long ago lost the respect of Darfuris he nominally represents, and now does little more than toe Khartoum’s line in speaking about the security situation and the need for the camps to be dismantled. He has become deeply corrupt, and is a fine example of NIF/NCP abilities to appropriate individuals and organizations for their own purposes.

El Tigani Sese, head of the Darfur Regional Authority and now widely regarded by Darfuris as corrupt and dishonest

Clearly at the regime’s behest, Sese recently offered outspoken support for the views of regime Second Vice-President Hasabo Mohamed Abdelrahman. In doing so, he has betrayed his people in deepest consequence:

According to Dr El Tijani Sese, the chairman of the Darfur Regional Authority (DRA), all areas formerly under control of the Darfur armed movements in the region are now secured by the Sudan Armed Forces. Tens of thousands of displaced and refugees have returned to their places of origin. Camp leaders strongly deny Sese’s report.

Reporting to the DRA Council in the North Darfur capital El Fasher on Thursday, Sese affirmed that the security situation in Darfur has become stable. “The region is now free of security threats. The people are freely moving around…”

Sese lauded the decisions of the governors [all Khartoum appointees–ER] of the five Darfur states to dismantle the camps for the displaced and transform a number of them into residential districts, as these camps “are not worthy for any Sudanese to live in…”

Several camp elders however described Sese’s speech as “sheer lies, fraud, and deception.” The spokesman for the Darfur Displaced and Refugees Association, Hussein Abu Sharati, strongly denied the figures presented by the DRA chairman. “I wonder if he can present us with a list of names of the villages and localities to which the displaced and refugees allegedly returned.

Sheikh Yousef Abdelrazeg, the coordinator of the Saraf Umra camps in North Darfur, challenged the DRA head to “take his vehicle from the DRA headquarters in El Fasher for a trip not further than one kilometre. I wonder what he will say then about secure situations in Darfur. “We wonder if Sese has not heard of the acts of murder, rape, robbery, and arson committed by militias in villages north of Kutum in North Darfur, south of Tabit in East Jebel Marra, and eastern Tur in South Darfur the past few weeks. Is he is living on another planet?” According to Abdelrazeg, Sese supports the Khartoum regime’s policies “only to keep his job and privileges.” (Radio Dabanga, December 12, 2015 | El Fasher)

[See Appendix 2 for a compendium of headlines for the last month, representing (if baldly) the extraordinary levels of violence that would confront all who are forcibly removed from the camps anywhere in Darfur.]

Unsurprisingly, Sese’s “authority” is regarded with contempt and deep distrust by Darfuris in the camps:

Displaced people living in Central Darfur state have rejected the project for the voluntary return of the displaced population, set up by the Darfur Regional Authority. “None of the displaced people will return to their home villages, because of the lack of security.” The coordinator of the Central Darfur camps said that the people refuse the voluntary return offered by the Darfur Regional Authority (DRA), “because the reasons for their displacement still exist.” He stressed that weapons from the militias should be collected, and criminals should be prosecuted, prior for the mass return of the displaced people. “We need to survive first before having institutions and buildings.” (Displaced refuse to obey Darfur Authority and leave camps | July 31, 2015 | Zalingei, formerly West Darfur / El Geneina, West Darfur)

Nonetheless, Sese is engaging not merely in servile rhetoric but in planning actions for which he provides Khartoum cover in their plans to dismantle the camps, as reported by SUDO/UK:

The Transitional Darfur Authority has formed committees to empty eight IDP Camps in Kass against the wishes of the displaced population that are present. The camps are home to some 235,000 people, many of whom have expressed concern over their personal safety outside of the camps. The Authority is planning to send the IDPs to the areas of Gerlang Banj, Rotoki, and Korley, all of which have newly been occupied by other settlers. (SUDO/UK | October 1, 2015)

Here we come face to face with the dangers the international community seems determined to ignore. If Sese and the Darfur Regional Authority are really planning to implement Khartoum’s policies, if they do in fact help in forcing IDPs to move “to the areas of Gerlang Banj, Rotoki, and Korley, all of which have newly been occupied by other [Arab] settlers,” then there will be massive bloodshed and it will be almost completely one-sided—and the DRA will be deeply complicit. The new Arab settlers on these lands have been heavily armed and people returning to lands that are theirs by right will stand no chance to make good their claims in the face of certain and overpowering violence. The past year has shown just how violent Darfur has become as genocidal counter-insurgency intensifies throughout Darfur (again, see “‘Changing the Demography’: Violent Expropriation and Destruction of Farmlands in Darfur, November 2014 – November 2015,” December 3, 2015).

Returning people to lands marked by such extraordinary violence is simply to accelerate the genocide.

APPENDIX 1: UN misrepresentations of Darfur’s realities and their consequences

The number of displaced persons in Darfur

Without a firm commitment to speak honestly about Darfur, the UN itself is ultimately complicit in Khartoum’s “final strategy” for the ravaged land, in the continuing violence, and in the failure to provide sufficient humanitarian capacity.

Disturbingly, the UN has for years consistently understated the figure for displaced persons, indeed sometimes—for expedient purposes—reduced the figure to a completely untenable level (see “UN Displacement Figures for Darfur: Assessment, Confused Guesses, or Dissimulation?” Sudan Tribune, December 20, 2015). The process began under Georg Charpentier, former head of UN humanitarian operations in Sudan from 2009 to 2011: he reduced the figure for displaced persons from 2.7 million (OCHA, January 1, 2009) to 1.9 million (Charpentier, July 2010)—a figure based on his “research,” which at a key juncture included reference to a non-existent report. But OCHA itself took this reduction in the number of IDPs much further: in its Sudan Humanitarian Bulletin #43 (November 4, 2012), the figure is “1.4 million Internally Displaced Persons in camps receiving food aid (WFP).”

I have on several occasions, going back to 2010, discussed in detail the absurdity of UN figures, and the untenable reduction by 1.3 million in the number of IDPs from the figure of January 1, 2009. Of particular note in trying to make sense of OCHA’s use of the figure of 1.4 million, even as qualified, are the staggering numbers of newly displaced persons during these years:

2007: 300,000 civilians newly displaced

2008: 317,000 civilians newly displaced

2009: 250,000 civilians newly displaced

2010: 300,000 civilians newly displaced

2011: 200,000 civilians newly displaced

2012: 150,000 civilians newly displaced

2013: 480,000 civilians newly displaced

2014: 430,000 civilians newly displaced

2015: 233,000 (as of December reporting 2015) civilians newly displaced

Total: over 2.6 million newly displaced, 2007 – 2015

(sources for all figures may be found in Appendix A of my December 20, 2015 analysis)

There are various ways to parse these data; one is to note that in the almost four years between January 1, 2009 (Darfur Humanitarian Profile No. 34, all iterations of which took very seriously figures for displacement) and the November 2012 OCHA weekly bulletin, 900,000 people had been newly displaced. And yet, incredibly, despite this massive new displacement, OCHA lowered its figure for displacement—by 500,000—to “1.4 million Internally Displaced Persons in camps receiving food aid (WFP).”

This occurred without explanation of new data sources or methodology—without any explanation at all. Unsurprising, OCHA eventually simply abandoned the figure—without explanation. But on its face, the figure of 1.4 million was always simply preposterous, given the estimate of 2.7 million for January 1, 2009 and the 900,000 who were subsequently displaced by the time OCHA issued its November 2012 estimate. Responsibility for this statistical grotesquerie has never been assigned, nor will it be. Georg Charpentier was duplicitous and finally destructive with his “calculation.” But the move from his July 2010 figure of 1.9 million to the OCHA November 2012 figure of 1.4 million—at a time of massive continuing displacement—will evidently never be explained.

Of one thing, however, we may be sure: at every step of the way Khartoum was pushing for a lower figure for the number of displaced. And to the extent the UN acquiesced, it supported Khartoum’s narrative about conditions improving and violence diminishing. It made sustaining the enormous, and enormously expensive, humanitarian operation in Darfur much more difficult. Conversely, UN statistical malfeasance made Khartoum’s job that much easier.

Malnutrition in Darfur

Similarly, UNICEF’s symptomatic refusal to promulgate publicly its 2014 report on malnutrition worked to obscure key humanitarian realities in Darfur until the document was leaked in outrage to Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times—obviously by someone appalled by UNICEF’s cynical self-censorship for Khartoum’s benefit. And certainly the withheld figures weakened efforts to avert severe malnutrition among children in Darfur. For to the extent the international humanitarian, and broader, community has been forced to fly blind on key issues of malnutrition in Darfur, UN complicity was perversely destructive. This point was made with force and clarity in the Tufts report:

Crucial information about the humanitarian situation is lacking. There are serious issues with the proper validation of the nutrition survey reports and their immediate release—without such data neither the government nor the international community can properly understand the severity of the humanitarian situation or the efficacy of the response.”

… international humanitarian capacities have been seriously eroded and impaired to a point that leaves Darfuris in a more vulnerable position now than at any other time since the counterinsurgency operations and forced displacements in 2003 and early 2004.” (“Navigating Without a Compass: The Erosion of Humanitarianism in Darfur”)

There clearly needs to be accountability, but we should expect none from a UN in which corruption becomes more stifling by the day.

APPENDIX 2: Compendium of violent incidents reported by Radio Dabanga over the past month

[See also “‘Changing the Demography’: Violent Expropriation and Destruction of Farmlands in Darfur, November 2014 – November 2015”]

Barrel bombs kill two children in Tawila, North Darfur | December 28, 2015 | Tawila, North Darfur

Two killed by barrel bombs in Darfur’s Jebel Marra | December 25, 2015 | Dubo el Omda, Jebel Marra

Darfur crime overview: Killings, ambushes in North Darfur | December 28, 2015 | Mukjar (formerly West Darfur) / Nyala, South Darfur / Tabit, North Darfur / Kabkabiya, North Darfur

Five kidnappings in Darfur this week | December 27, 2015 | Darfur

Soldiers rape woman, abduct brother in Darfur | December 26, 2015 | Fanga, North Darfur

Another farmer killed, protest march in El Fasher | December, 2015 | El Fasher, North Darfur

One killed, five wounded in Central (formerly West Darfur) Darfur camp attack | December 25, 2015 | Bindisi

Two gang-raped near Tabit, North Darfur | December 24, 2015 | Tawila, North Darfur

Student’s bullet-riddled body found in Central Darfur camp | December 24, 2015 | Garsila, formerly West Darfur

Farmers protest against herders’ attacks in North Darfur capital | December 23, 2015 | El Fasher

Village burned to ground in Tawila, North Darfur | December 22, 2015 | Tawila

18-year-old woman raped by seven in North Darfur | December 22, 2015 | Zamzam camp, North Darfur

Militiamen plunder homes in Tabit, North Darfur | December 21, 2015 | Tabit

Schoolgirl gang-raped in North Darfur | December 21, 2015 | Tawila

Villager killed, robbed in North Darfur | December 21, 2015 | Tabit

Police convoy attacked in South Darfur | December 20, 2015 | Bielel, South Darfur

North Darfur woman raped for five hours | December 20, 2015 | Kutum, North Darfur

Gunmen threaten to torch Central Darfur camp, market | December 20, 2015 | Bindisi, formally West Darfur

Rapists steal North Darfur woman’s sheep| December 19, 2015 | El Fasher

Herders shoot farmers in North and South Darfur | December 17, 2015 | El Fasher / Gireida, South Darfur

Woman raped for hours in Tawila, North Darfur | December 17, 2015 | Tawila

UN OCHA: More than 400,000 newly displaced in Sudan this year | December 17, 2015 | Khartoum

Two gang-raped in North Darfur’s Tawila locality | December 16, 2015 | Tawila

Newly displaced in North Darfur’s Tabit living rough | December 16, 2015 | Tabit

Barrel bombs dropped near Fanga in Darfur’s Jebel Marra | December 15, 2015 | Fanga, North Darfur

North Darfur’s Shangil Tobaya ‘besieged’ | December 15, 2015 | Shangil Tobaya, North Darfur

Gang-rape south of Tabit, Nort Darfur | December 14, 2015 | Tabit

Sudanese refugee killed in eastern Chad | December 14, 2015 | Eastern Chad

Livestock stolen from North Darfur village | December 14, 2015 | Kutum

Darfur crime overview: Students stabbed in North Darfur’s Kutum | December 14, 2015 | Dabanga Sudan

Sudan Air Force continues bombing East Jebel Marra | December 14, 2015 | El Aradeib El Ashara

14 dead in South Darfur fighting between farmers, herders | December 13, 2015 | Bulbul, South Darfur

One killed, two raped in North Darfur nomad settlement | December 13, 2015 | Tabit

Two Darfur women abducted in East Jebel Marra | December 11, 2015 | Mashrou Abu Zeid, North Darfur

North Darfur merchant released after payment of ransom | December 11, 2015 | Kutum

Air attack on Darfur’s East Jebel Marra | December 11, 2015 | Dubo El Omda, North Darfur

Child killed in grenade explosion in Darfur’s East Jebel Marra | December 11, 2015 | Tamara, North Darfur

Girl raped by four near Tabit, North Darfur | December 10, 2015 | Tabit

Farmer killed, another wounded in Darfur’s East Jebel Marra | December 10, 2015 | Taradona, North Darfur

North Darfur’s Saraf Umra tyrannised by local militias | December 10, 2015 | Saraf Umra, North Darfur

Sudanese paramilitaries attack Tur, South DarfurDecember 9, 2015 | Tur, South Darfur |

Farmers attacked, crops destroyed in Darfur | December 9, 2015 | Bindisi / Mukjar / Kubum

Sudanese Air Force bombs well near Tabit, North Darfur | December 8, 2015 | Tabit

Two gang-raped near North Darfur’s Tabit | December 7, 2015 | Tabit

North Darfur: Newly displaced arrive in Um Baru | December 7, 2015 | Kutum / Um Baru

East Jebel Marra villages cleared: Three Darfur children die | December 6, 2015 | East Jebel Marra

Man killed, three women raped in Darfur’s East Jebel Marra | December 6, 2015 | East Jebel Marra

Two dead, two injured in West Darfur shootings | December 6, 2015 | Sirba, West Darfur

Darfur’s Kutum raids: one person killed, cattle theft | December 4, 2015 | Anka, North Darfur

Many displaced by attacks in Darfur’s Jebel Marra | December 4, 2015 | Tabit

Gunmen abduct merchant in North Darfur | December 4, 2015 | Kutum

Thousands return to Central Darfur despite insecurity | December 4, 2015 | Um Dukhun

Two East Jebel Marra villages attacked | December 4, 2015 | Koto / Dali

Militia continue to attack villages in North Darfur’s Kutum | December 3, 2015 | Kutum

Three dead in Central Darfur tribal fighting | December 3, 2015 | Um Dukhun

Boy sees mother, sister raped in North Darfur | December 2, 2015 | Shangil Tobaya, North Darfur

One killed, six abducted in Kutum raids | December 2, 2015 | Kutum

Woman raped by two in North Darfur’s Tabit | December 1, 2015 | Tabit

Village sheikh strangled in Kabkabiya, North Darfur | December 1, 2015 | Kabkabiya, North Darfur