Eric Reeves on himself and Sudan, September 2014

Eric Reeves, 2014

For more than fifteen years I’ve worked long hours every week attempting to bring a just peace to greater Sudan, now including Sudan and South Sudan. It is the most daunting and perhaps dispiriting of advocacy tasks, but I’ve not been tempted to give up—tempted, perhaps, but never so much as to end my efforts. At the same time, were greater Sudan actually, magically to achieve a just and inclusive peace, my advocacy days would be over. I’m certainly not tempted to move on to another country or another issue, in part because of the grim realities and lack of progress toward this present goal. But the constant temptation to lay down the burden, to pass on whatever mantle I wear, continually gives way to the pull on my heart of the Sudanese people, in ways evermore powerful. Sudan has become what I do, and what I care most about in worldly affairs. Although often asked by news organizations, I don’t offer opinions—at least for publication or broadcast—on other African countries, or other foreign policy issues. I haven’t nearly the knowledge about them that I do of Sudan, and I squander what credibility I may have by speaking about issues I know less well.

The fact of such deep engagement with work on Sudan still surprises me; I catch myself wondering, “how does this very peculiar turn of events connect with all that I did before in my life?” I began working on Sudan when I was 49 years old and had not been politically active—excepting faculty politics at Smith College, where I have taught for 35 years—or engaged in any sort of advocacy work. I don’t think I have a very good answer as to why, and when I’m asked, I typically retreat into a literary explanation, suggesting a reading of the profound, parable-like short story by Ursula LeGuin, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” I won’t presume to summarize this powerful examination of the most basic human decisions, but suffice it to say that the story presents the terms in which I think of my own moral life.

I will say that explaining this mid-life transformation has often been frustratingly difficult, and hence the present essay. One reason is that as a well-established, or at least tenured professor of English, I’ve been constantly forced to deal with skeptical queries about my expertise on Sudan, dismissive characterizations of my background, even outright contempt. The evident assumption by some is that the research skills from one academic domain have no portability, that no matter how much reading, research, interviewing, and assessment work I’ve done over fifteen years, I’m not qualified to write about Sudan. I think this is nonsense, driven in part, for some, by envy of my lengthy record of publication on Sudan and the frequency with which I am interviewed by the BBC, Radio France Internationale, and many others.

I’ve also repeatedly been forced to answer to the charge, often explicit, that I’ve made only one month-long trip to Sudan, and that in January 2003, so what can I possibly know of this country? By contrast, I like to consider as representative the opinions of numerous Sudanese and leading students of Sudan offered on the occasion of my publishing a lengthy e-Book, Compromising with Evil: An archival history of greater Sudan, 2007 – 2012 (2012). There is no other way in which I can speak to this accusation of ignorance, other than to point out that I have many scores of Sudanese friends and contacts, many of them highly informed about events in both Sudan and South Sudan.

Mohammed Ahmed Eisa, Darfuri activist and the former director of the Amal Center for the Treatment and Rehabilitation of Victims of Torture; Robert F. Kennedy human rights award laureate for 2007. It is to “Dr. Mohamed,” as he affectionately known to friends, that I dedicated Compromising with Evil. He also offered a most generous assessment of the book’s achievements.

As it happens January 2003 was also the month in which I learned I had leukemia, and after a brief period of being asymptomatic, the illness attacked with a vengeance in late 2004. The past ten years have been a time of great trial, and treatment has left me without a fully functioning immune system and extremely vulnerable on many medical fronts: I simply could not safely travel back to South Sudan, in part because the stem cell transplant that saved my life in 2008 continues to haunt me. I am seriously immuno-suppressed, highly susceptible to dangerous pneumonias, and can’t be inoculated with any live virus vaccines, several of which are necessary for travel to South Sudan (the Khartoum regime would never grant me a visa or travel permit for Sudan). But I feel no less impassioned at a distance about the cause that chose me, and continues to choose me. For I hear constantly from the people of Sudan, north and south, telling me—often in poor, but unembarrassed English—that I am their voice to the world, that I speak as if from their heart—and that someday I will be welcome into their homes and towns. Although this is an unlikely event, the passion and gratefulness represented by the invitations is poignantly gratifying.

But it also imposes a terrible burden of responsibility. For if what I hear from my Sudanese friends—most completely unknown to me in a personal sense—is true, then advocacy for a just peace in greater Sudan has become my inescapable cause; and judging from recent and current events, that cause will need advocates for many years to come. Sudan profoundly defines my life even at a distance of 7,000 miles.

My work began in January 1999, following a lengthy conversation with the head of Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)/USA, Joelle Tanguy.

Joelle Tanguy

The organization had for a number of years been the beneficiary of gallery profits from my woodturning, a craft art I’d learned as a teenager and returned to some thirty years later, finding that I had more talent than I imagined, at least judging by gallery sales. Joelle and I were speaking about the various places where MSF worked, and our attention swung inevitably to southern Sudan, which she lamented as a conflict both lengthy and apparently intractable—not ideal for an international organization that views itself as an emergency medical response resource.

Not only was the conflict intractable, but MSF and others had begun to worry that humanitarian assistance was increasingly being commandeered by the southern rebel army, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army—and that this was actually sustaining conflict. Joelle looked away wistfully at one point, saying only, “Sudan needs a champion .…” She was most definitely not thinking of me, whom she knew only as a generous woodturner. But something happened—to this day I really don’t know what—and I said simply, with what might have seemed pure arrogance, that “I would see what I could do.” Joelle was surely much amused by my words, though her thoughts about this fateful moment may have shifted over the past fifteen years. I of course had no idea what this declaration would come to mean for my life—none.

I did, however, begin work immediately on returning from New York City, and my attention was immediately drawn to the role oil was then playing in the conflict, especially in an area then known as Western Upper Nile (now essentially Unity State in South Sudan). And in attempting to highlight the complicity of the Canadian oil company Talisman Energy in the growing carnage, I discovered in May 1999 the power of the op/ed as a genre. It was a critical lesson.

On May 4, 1999 Canada’s national newspaper, The Globe and Mail, published my account of what was occurring in this part of Sudan under the title “Don’t Let Oil Revenues in Sudan Fuel Genocide.” A blunt instrument of a title to be sure (and not my choice), but a contact I’d developed in the Canadian foreign ministry whispered to me in a telephone conversation the day it appeared, “That thing went off like a bomb in this building!” Canadians are famously too polite to write such a brutally critical piece; whether true or not, an American English professor had helped set in motion events that would eventually lead Foreign Minister Lloyd Axworthy to appoint a commission of inquiry, which reported in January 2000 that the realities I had written about were in fact borne out by what they saw and the witnesses they’d interviewed (“Human Security in Sudan,” January 2000).

Although I continued to write about Talisman’s role in the oil regions of Sudan, I’d also begun a more specific advocacy effort: a divestment campaign targeting Talisman shares trading on the New York Stock Exchange. I began again by means of an op/ed, this time in The Los Angeles Times (30 August 1999): “As in South Africa, It’s Time to Let Our Wallets Do the Talking.” There soon came to be what oil analysts called a “Sudan overhang” in Talisman share price—a roughly 25 percent decline in what should have been the stock’s approximate share price. The reason was clear: in a little over two years, every American public institutional shareholder of Talisman stock had divested—big ones, in states like Texas, California, New York, Wisconsin and others. The pension giant TIAA-CREF also unloaded all their shares. It was inevitable that Talisman would be forced to withdraw—and in 2004 they did, taking with them irreplaceable technical expertise, access to world capital markets, and strong managerial capacity.

Working Alone

The effect of these early “no holds barred” publications convinced me that I worked best alone, as I had for my entire professional career (I began teaching at Smith College in 1979). The longer I worked on Sudan, the less I wanted what seemed to me the encumbrances of organizational or institutional affiliation with any particular human rights group, or coalition, or political movement. I wanted to be able to say clearly and honestly what my research revealed, I wanted to vet my own sources, and I wanted to do all this on my timetable—which always means urgently. As this became clear to a wider audience of those in Sudan and working on Sudan policy, and as my readers increased rapidly in number, I became the beneficiary of an increasing number of confidential sources, who knew that I could be counted on both to protect identities scrupulously, but also to see that the information provided to me—if I fully trusted the source—would be read by many people, and in the very near term following my receiving the original communication. At least one of my sources became the focus of an intense UN internal investigation in 2001 following a particularly explosive leaking of information about the oil regions; but communication intercepts were harder a decade ago, and my source only recently left her UN position in Sudan.

At the same time, while committed to working alone, I made wonderful friends, both Sudanese and among the many friends of Sudan. This has been one of the great redeeming features of work that too often removes me from social interaction. I benefit enormously from having a remarkable group of people who both understand why I do what I do, understand its importance, and offer solace, company of various kinds (a few exclusively via email), and heartfelt expressions of appreciation. They mean the world to me, in many ways they are my world, and I could not continue without them. I would name some of them here, but fear that too many would be omitted. I will mention only my great friend and brother in the cause, Ted Dagne. Himself a refugee from Ethiopia during the tyrannical Mengistu regime, Ted is the person to whom I feel closest in all of this work. He is dedicated, overwhelmingly dedicated to the cause of South Sudan; he is tireless and selfless in his work, which has taken various forms; and he truly has the heart of a lion. He is physically fearless and cannot abide dissimulation. He is my moral and political compass on all matters relating to South Sudan.

Ted Dagne in his Congressional Research Service office

In Sudan

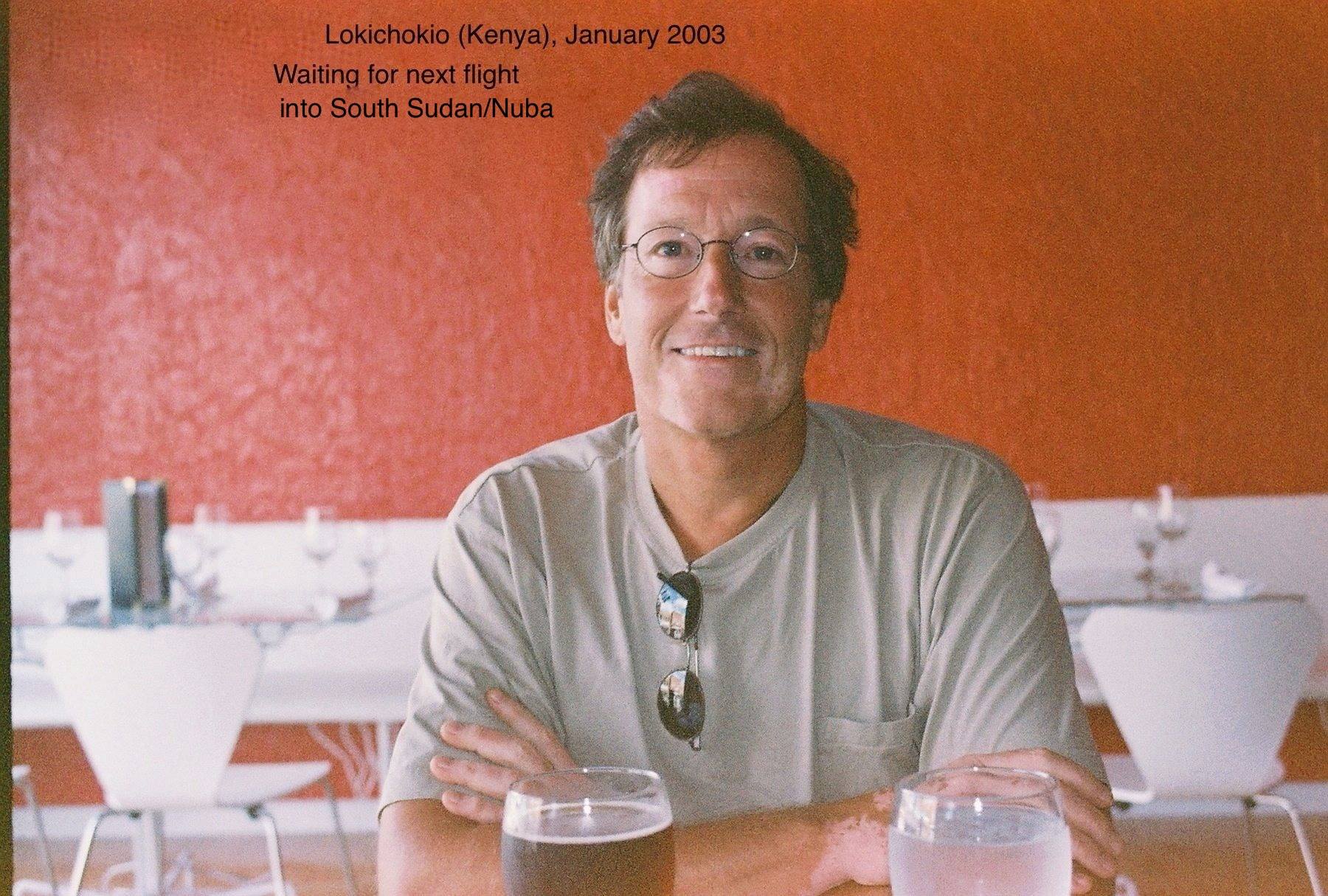

In January 2003 I finally made my first and only trip to Sudan. I traveled first to Nairobi and from there to Lokichokkio in northern Kenya. Over the coming weeks I would travel to Marial Bai, Rumbek, Yei, Lui, Mundri, and the Nuba Mountains in northern Sudan—the most powerfully moving days of my time in Sudan. I had got myself in particularly good shape, since walking is the primary form of transportation in many locations; I’d thought carefully about what to take (besides my anti-malarial drugs and my camera); and was prepared to deal with the uncertainty of getting around. I was traveling completely independently, had no advance plans, and paid for my own airfare. But that could get me only as far as Loki (as it was called by all). For of course at the time there was no commercial air transport into South Sudan: I was obliged to “hitch” a flight over beer at the local watering hole in Loki. Tukuls in the Kauda Valley of the Nuba Mountains (Photograph by Eric Reeves, January 2003)

Tukuls in the Kauda Valley of the Nuba Mountains (Photograph by Eric Reeves, January 2003)

Woman working with thatch, Kauda Valley of the Nuba Mountains (Photograph by Eric Reeves, January 2003)

Woman working with thatch, Kauda Valley of the Nuba Mountains (Photograph by Eric Reeves, January 2003)

Dinka boy with cattle, Rumbek, Lakes State (Photograph by Eric Reeves, January 2003)

Irish GOAL was accommodating, gave me a seat, and I was, quite fortuitously, out of Loki and into Sudan the following day. My destination was Rumbek in Lakes State; but before going there the GOAL team needed to make stops, including one in Marial Bai in the far northwestern part of Bahr el-Ghazal. Since I’d begun the flight in what was essentially the southeastern corner South Sudan, the trip took what seemed forever in our single-prop aircraft. But it was a chance to feel the vastness of the land—and to see how completely without development it remained 47 years after the nominal independence of Sudan from Anglo-Egyptian Condominium rule. There were no roads, no wires for telephone or electricity (and what would they connect with wherever they might lead?), no signs of an integrated economy. Mainly I saw just vast tracks of land stretching to the horizon; there were almost no villages visible.

When I finally made it to Rumbek, news was coming to me first-hand—fighting persisted in many nearby regions and Khartoum was violating the terms of an October 2002 ceasefire. Hearing of this in “real time” from the investigators based in Rumbek, I was able to commandeer a laptop to draft a brief report on what was occurring, and received permission from the Civilian Protection Monitoring Team (CPMT) to use their satellite communications gear for 45 minutes to send it to anyone whose email address I could remember (and I urged them to forward on the information).

Back in Loki I was able to write at greater leisure as I waited for my next flight into Sudan and used the erratic Internet again to email news. And some of the news was extraordinary, as highly confidential information was passed on to me in the form of photographs showing that Khartoum’s Sudan Armed Forces were clearly abusing the terms of the October 2002 agreement by moving barges of military equipment southward on the White Nile River. Humanitarian security personnel in Loki had heard of me, and over beers I was again vetted, found trustworthy, and have stayed in touch with one official ever since.

Woman in the Yei market; just out of sight is a foxhole meant to serve as protection in the event Khartoum attacks with Antonov bombings (see below)

Such foxholes were everywhere in 2003—a testament to the fear generated by the Anontov bombings. The Antonov is a retrofitted Russian cargo plane with no targeting accuracy; it is useless for military purposes and is an instrument of civilian terror.

Women and children at a water bore-hole in the hills above Kauda

My days in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan came in the middle of my time in Sudan/Loki, but they were extraordinary days. I flew into Kauda, drove past the northern Sudanese military checkpoint (more than a bit unnerving, given what I had written about the regime in Khartoum by this time), and to the NGO tukul that was to be my home for a few days.

The Kauda valley in the very center of the Nuba Mountains is a truly beautiful place, one of the most beautiful I’ve ever encountered. The hillsides are alive with tukuls, and terraced landscapes that give the impression of always having been there—of belonging there.

A typical view in the Kauda Valley of the Nuba Mountains

During my days near Kauda I took long walks into the remoter regions of the valley, taking many pictures and communicating awkwardly with folks I met. My camera seemed the perfect translation tool, as most of the people I photographed had never had the experience before, especially the children. And when they saw themselves—typically for the first time in their lives—in my flip-out monitor, the inevitable reaction (once recognition took place—not always an immediate process) was unconstrained laughter. I’m not sure I understood the laughter, or that there was much to understand beyond the fact that seeing themselves was hugely entertaining and out of the ordinary.

Girls in the Nuba, vastly amused by my photographic antics

Boy in the Nuba, puzzled by my camera

I attended a local church service in Kauda town, where I was welcomed graciously, and every word not sung was laboriously (and in places bewilderingly) translated for me. This made the service rather long, but it was a sign of real appreciation. Afterwards there was a beautiful interweaving of communicants, walking in opposite directions around the church. All the women and children were in colorful finery, and the men were dressed in their best attire.

But I also attended a much grimmer gathering, in the rocky hillside well above Kauda: a meeting of Nuba military and civil society leaders, led by the deputy governor of the region (the governor was in Nairobi), in a large tent set up for this occasion. These people, having heard about me, were determined that I should hear their story, and they were deadly serious in telling it. Again and again I felt the force of decades of anger and disappointment pushing me back in my seat. I learned first-hand how bitter the people of the Nuba were, having been left out of consideration at the time of independence (1956), and in the Addis Ababa peace agreement (1972) that ended Sudan’s first civil war. They would not be left out of the next peace agreement they insisted, with a vehemence that was almost shocking, and clearly meant to be conveyed to those in whose hands their fate rested.

The Nuba, a group of related African tribal groups in this central region, knew that key decisions were going to be made about their future, and they wanted a voice. Most of all they wanted self-determination, even as they knew that the Nuba Mountains were not only north of the 1956 boundary between northern and southern Sudan—now two different countries—but were nowhere contiguous with what became the Republic of South Sudan on July 9, 2011 Their fear was that they would be left alone in a (north) Sudan dominated by Khartoum’s ideological Islam and Arabism (African people of the Nuba are quite tolerant and follow a number of religions, including Islam).

And their worst fears have been realized. The Kauda valley I found so movingly beautiful has become the epicenter of aerial attacks by Khartoum’s military forces, attacks that have destroyed the region’s agricultural production, destroyed countless villages, and have left (according to UN figures) more than a million people displaced or in acute need of humanitarian assistance in South Kordofan State, where the Nuba Mountains are located. For over three years Khartoum has imposed a total humanitarian embargo on areas controlled by the rebel movement, made up of many of the men and women I met in January 2003.

Deputy Governor Ismail Khamis had told me bluntly on the occasion of our meeting, “Khartoum doesn’t regard us as human beings.” Given such attitudes, the Nuba believe, it was clear to me—then and now—that the Nuba are defending their homeland and their way of life. They have no alternative: as Khamis said to me during our 2003 meeting, “we have no way out.” Given the geography of South Kordofan, there can be little quarreling with this assessment. That said, it is clear that these people will fight bravely to the death, and have demonstrated much courage and military prowess since Khartoum’s military assault on the region began in June of 2011. Still, the power of relentless aerial bombardment, the consequences of deliberate human displacement, and the destruction of the Nuba agricultural economy are taking a terrible toll on the Nuba as a whole. Malnutrition rates have soared; many have fled to South Sudan as refugees; many have died. By the end of June 2011, I argued in a piece that appeared in Dissent Magazine that we were yet again confronting genocidal destruction—a reprise of what the jihadist campaign of annihilation mounted by this same Khartoum regime in the 1990s, a campaign that very nearly succeeded. And a reprise as well of events in Darfur, as I’ll suggest in a moment.

In the current world of human rights and peace advocacy, there is one great leveler of influence, even for “Lone Rangers” such as myself. For we live in an age of digital electronic communication, by which I mean various kinds of computers and computer-like devices, word processing, email, faxes, PDFs, websites, portable and satellite telephones, satellite imagery in real time—all of which continue to offer the potential for exponentially greater advocacy power as these technologies rapidly improve. Jody Williams, co-recipient of the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize for her work in the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, was asked how she got so much done in such a relatively short space of time. Her one-word answer: “email.” And those of us who remember how relatively primitive email was in 1997 know full well how much more powerful this tool is now.

“Sudan Central”–where I work

I have leveraged my very large email list-serve, along with all the forms of electronic communication readily available, to the very maximum. My primary website receives hundreds of page views a day; two other websites related to my primary site also receive substantial traffic. Several social media tools have greatly expanded the reach of all that I write, and Twitter in particular seems well-suited for this kind of work, where I have some 2,400 followers. Moreover, there is considerable self-selection reflected in this readership: primarily Sudanese from all over Sudan and the diaspora, but also a great many journalists (many covering Africa and many senior reporters or editors), NGO staff in Sudan and in their organizational headquarters, academics and students of Sudan, think tanks, UN personnel, U.S. and other country governmental officials with responsibility for Sudan policy, advocacy groups—and individuals. Pieces I publish on my website and social media sites can often have hundreds of thousands of readers, or at least be forwarded as a link to the piece on my website.

The immediate occasion for beginning this retrospective essay, beyond the need to have an autobiographical sketch to which I can refer people, has been my ongoing reflection about the meaning of the tenth anniversary of my Washington Post op/ed (“Unnoticed Genocide,” February 25, 2004) which turns out to have been the first and most prominent declaration that what was occurring in the Darfur region of western Sudan was clearly genocide. Evidence had been emerging for over a year suggesting something monstrous was unfolding as the Khartoum regime responded to rebellion by the (then-united) Sudan Liberation Army, which had wide support in its battling years of marginalization, harassment, absence of services, a totally incompetent judiciary, and growing land appropriation by Arab tribal groups. The idea of having written about genocide ten years ago, and finding that it is still the central task in my Sudan advocacy, seemed perverse enough to stimulate further self-reflection, and the implications of what I’ve come to know about this tortured region.

Khartoum has engaged in brutal, comprehensive destruction of African villages and agricultural resources—and continues to do so. The photograph below is by Mia Farrow, 2007

The level of destruction wrought me ground and aerial assaults is almost inconceivable. (Aerial photograph by Brian Steidle, 2005)

Khartoum’s counter-insurgency response in Darfur—after a series of early punishing military losses—was not an ordinary military campaign. Recruiting, arming, and working in concert with the notorious Arab militias known as the Janjaweed, Khartoum’s forces began the systematic destruction of African villages, populations, and means of living. Thousands of African villages were partially or wholly destroyed, including the poisoning of wells, burning of homes, torching of food and seed stocks (Arab villages, sometimes only a few hundred yards away, were left untouched). Fleeing civilians—including women, children, and the infirm—were killed by men pursuing them on horses and camels, shooting with automatic weapons. Helicopter gunships and fixed-wing aircraft attacked with immensely destructive force countless civilian targets with no military presence. Girls and women were raped by the thousands—an onslaught of sexual violence continues to this day. After more than a decade of violence and displacement, it is a grim certainty that tens of thousands of girls and women have been sexually assaulted.

Victim of rape, scarred to make the shame and fact of rape more visible (Photograph by Mia Farrow)

As the father of two daughters, I find the accounts of rape simply overwhelming; for all too often they are gang-rapes of girls over many hours—and in front of their families, who are forced to watch what is often a fatal brutalizing of young bodies. Indeed, these accounts are so horrific that I can barely force myself to read them. They—of the thousands of dispatches and news stories I’ve read about Darfur—create the greatest sense of both sorrow and rage. And though it is a dismaying—and personally costly—way to gain strength, I’ve found throughout my Sudan career that such rage energizes, compels, and will not allow me to end a day in which I’ve set myself a particular task. I should say as well that the vast and impotent UN presence in Darfur, which refuses to report meaningfully on this terrible scourge of rape, is also the cause of a perversely energizing rage.

The purpose of all Khartoum’s actions—chronicled fitfully in the early months, but evermore fully throughout 2003—was to destroy these African tribal groups “as such,” to use the key definitional phrase from the 1948 UN Genocide Convention. Innumerable reports, countless interviews and dispatches from the ground, satellite and aerial overflights—all made clear what was happening. I found it extraordinary to write a brief account of all this and have it given the title “Unnoticed Genocide”: how “unnoticed”? How could this most basic inference not be drawn? Reports from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, intrepid journalists, and humanitarians on the ground made clear that “war” in Darfur amounted to widespread, systematic, ethnically-targeted violence—and yet no one had made the claim that this was genocide, which was then at its very height, though indeed largely unnoticed.

Despite later legal sophistry and confusion about the meaning of “genocidal intent,” Darfur would not long remain “unnoticed,” and from 2004 through 2008 Darfur became an extraordinary cause for American and international civil advocacy. Moreover, during this period both the UN General Assembly and Security Council formally and unanimously endorsed the international “responsibility to protect” civilians attacked from without, or indeed by their own government. As events would reveal, Sir Kiernan Prendergast—UN Undersecretary for Political Affairs at the time—was cynically right to declare, if with dismaying equanimity, that no one took such fine-sounding words seriously. This is clear in an interview from a 2007 Frontline/CBC documentary (“On Our Watch“), directed by Neil Docherty and still the best we have on Darfur.

And yet the cause of Darfur persisted. Newspapers devoted significant column inches and opinion page space to an exceedingly remote region that a decade earlier virtually no one could have identified on a map. In this country, student groups, human rights advocates, Jewish organizations and synagogues, celebrities, even political figures made of Darfur a cause like no other in recent American foreign policy advocacy, apartheid-era South Africa notwithstanding.

But as quickly as the movement built, it dissipated. Though not organizationally affiliated, I was certainly working with a number of Darfur advocacy groups, and continuing to publish extensively on the region and participate in advocacy planning. And yet even with this “insider’s” vantage, I cannot explain to those who would later ask, “Whatever happened to Darfur? Are things better there now?” I could only groan inwardly in despair given what I knew was occurring on a daily basis in this tortured land. The reasons for the collapse of the Darfur advocacy movement are many and some are complex; I won’t pretend to understand how things came to such an abrupt halt. Certainly it must be said, however, that without seeing any change in international policies—or on the ground—political weariness among activists became palpable and perhaps inevitable, certainly something Khartoum had long banked on.

Moreover, the move from the Bush administration to the Obama administration was generally a disaster for greater Sudan. Obama had said great and stirring things about Darfur during the 2008 campaign, and even earlier during his Senate years. Hopes were high among the various constituencies that both worked on Darfur and supported Obama. But those hopes were badly misplaced, and Obama’s first action was to repay a campaign debt by appointing retired Air Force Major General Scott Gration as special envoy for Sudan—a giant step, in Gration’s mind, toward his much desired appointment to the ambassadorship in Nairobi. But for Sudan, the appointment—by all accounts—was an utter catastrophe.

Gration had no diplomatic skills or experience, was familiar with none of the relevant languages, and completely failed to understand the nature of the regime in Khartoum. Hearts sank when he declared that countries are like kids: they need, he said in a notorious interview with The Washington Post (September 2009), to be rewarded with “gold stars” and “happy faces.” Gration was speaking here of “rewarding” a regime comprising numerous serial génocidaires; in fact, President Omar al-Bashir has been indicted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and multiple counts of genocide. His Defense Minister (and former Minister of the Interior during the worst years of the Darfur genocide) has also been indicted by the ICC. I simply could not comprehend how utterly incompetent Gration was, how he could have been appointed to such an important and singularly challenging diplomatic post. Mine was a response felt by a great many people working in a wide range of capacities in Sudan. If there was a low point in my work on Darfur and Sudan generally, it came with Gration’s appointment.

Sizing up the new administration and its presidential envoy for Sudan, Khartoum felt emboldened by the weakening U.S. diplomatic posture and the almost total lack of pressure from the Europeans, the African Union, and the UN. In March 2009 the regime shamelessly expelled thirteen of the most important humanitarian organizations working in Darfur—roughly half the total relief capacity at the time. The most recent report at the time from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated that 2.7 million people were displaced into camps—and this did not include the refugees in eastern Chad or displaced persons not in camps. The estimate for “conflict-affected persons”—in need of some form of assistance—was 4.7 million. Despite this tremendous need for humanitarian aid, Gration, then Senator John Kerry, and others in the Obama administration prevaricated—as did the Europeans—and the expulsions were accepted. This ruthless, wholesale set of expulsions sent a clear message to remaining humanitarians: “don’t speak out about what you see or you will join those expelled.” And there have indeed been subsequent expulsions, threats of expulsions, as well as deliberate efforts to make insecurity intolerable for aid workers.

By 2008 Khartoum had also been convinced the UN was not serious about protecting civilians in Darfur, a conclusion made inevitable by deployment of a UN/African Union “hybrid” force known as UNAMID. The force remains badly equipped, is without remotely adequate air transport or protective force, has many troops that don’t meet minimum UN peacekeeping standards, and has lost more than fifty of their numbers in firefights. The force has been relentlessly abused and obstructed by Khartoum’s military and security forces, despite the Status of Forces Agreement (January 2008) guaranteeing complete freedom of movement. Moreover, Khartoum’s militia forces have been clearly implicated in several of the deadliest attacks on UNAMID. In the end, as I had argued long and strenuously, the force designed to protect civilians and humanitarians in Darfur became badly demoralized and unwilling to undertake even those protection tasks of which it is capable.

UNAMID—in “inaction,” and failing to protect unarmed civilians near Kutum, North Darfur

Although the primary animus of Khartoum’s military assault and campaign of genocidal attrition was directed against the non-Arab/African populations, who make up the overwhelming majority of those killed and attempting to survive in displaced persons camps, violence was becoming more widespread, with ever greater involvement by Arab tribes fighting among themselves in the wake of the massive demographic shift that had occurred in Darfur, indeed defined Khartoum’s strategy. In their 2005 book on Darfur, Julie Flint and Alex de Waal report (as have others):

The ultimate objective in Darfur is spelled out in an August 2004 directive from [Janjaweed paramount leader Musa] Hilal’s headquarters: “change the demography” of Darfur and “empty it of African tribes.” Confirming the control of [Khartoum’s] Military Intelligence over the Darfur file, the directive is addressed to no fewer than three intelligence services—the Intelligence and Security Department, Military Intelligence and National Security, and the ultra-secret “Constructive Security,” or Amn al Ijabi. (Darfur: A Short History of a Long War, 2005)

The situation had become complexly violent and destructive, yet nearly always serving Khartoum’s purposes in one way or another that in 2007 Human Rights Watch appropriately called violence in Darfur “chaos by design.” Looking at the origins of the conflict, as well as the consequences of continuing insecurity, the ongoing epidemic of rape, obstruction of humanitarian aid, and the continuing massive displacement of African populations, I felt that we needed a new term for what was still ethnically-targeted violence and destruction, amidst rapidly growing chaos, yet still serving Khartoum’s original purposes. My phrase, for this and the title for another piece in The Washington Post (April 2008), was “genocide by attrition.”

This attrition among African populations did not exclude extreme hardship, illness, and death among Arab populations caught in the chaos; and Arab inter-tribal fighting continues to be extremely intense in various places, with thousands of total casualties. And we hear almost nothing about the more than 350,000 Darfuri refugees in eastern Chad who continue to live in appalling circumstances, yet fear to return to their lands and homes because of rampant insecurity. But we should be clear that those internally displaced, whether registered or not, are overwhelmingly from non-Arab or African tribal groups. Destruction still has a decisive ethnic inflection, and yet because there has been no virtually no international news access to Darfur for years, this fact has become obscured in hazy UN reports and even misleading news accounts. Even more troubling, we’ve had very little global humanitarian data during this period and there is much that portends catastrophe in the near future. Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) figures for Darfur have not been released by the UN for years—because Khartoum has dictated that they be not. And yet GAM data are some of the most important we have in assessing a humanitarian crisis.

In February 2004, I concluded my Washington Post op-ed on Darfur with the following warning:

There can be no reasonable skepticism about Khartoum’s use of these militias to ‘destroy, in whole or in part, ethnic or racial groups’—in short, to commit genocide. Khartoum has so far refused to rein in its Arab militias; has refused to enter into meaningful peace talks with the insurgency groups; and, most disturbingly, has refused to grant unrestricted humanitarian access. The international community has been slow to react to Darfur’s catastrophe and has yet to move with sufficient urgency and commitment. A credible peace forum must be rapidly created. Immediate plans for humanitarian intervention should begin. The alternative is to allow tens of thousands of civilians to die in the weeks and months ahead in what will be continuing genocidal destruction.

Painfully little of this requires updating, other than the mortality estimate. For mortality studies conducted up until late 2009 suggest that at least 400,000 people have died (my own extensive research, culminating in a 2010 summary of statistical evidence and using additional data, suggests a figure closer to 500,000). News reporting uses the UN figure of 300,000 but this only emphasizes the UN’s perverse habit of under-reporting Darfur’s realities. The figure was very crudely, indeed extemporaneously calculated by UN humanitarian chief John Holmes in April 2008—over six years ago.

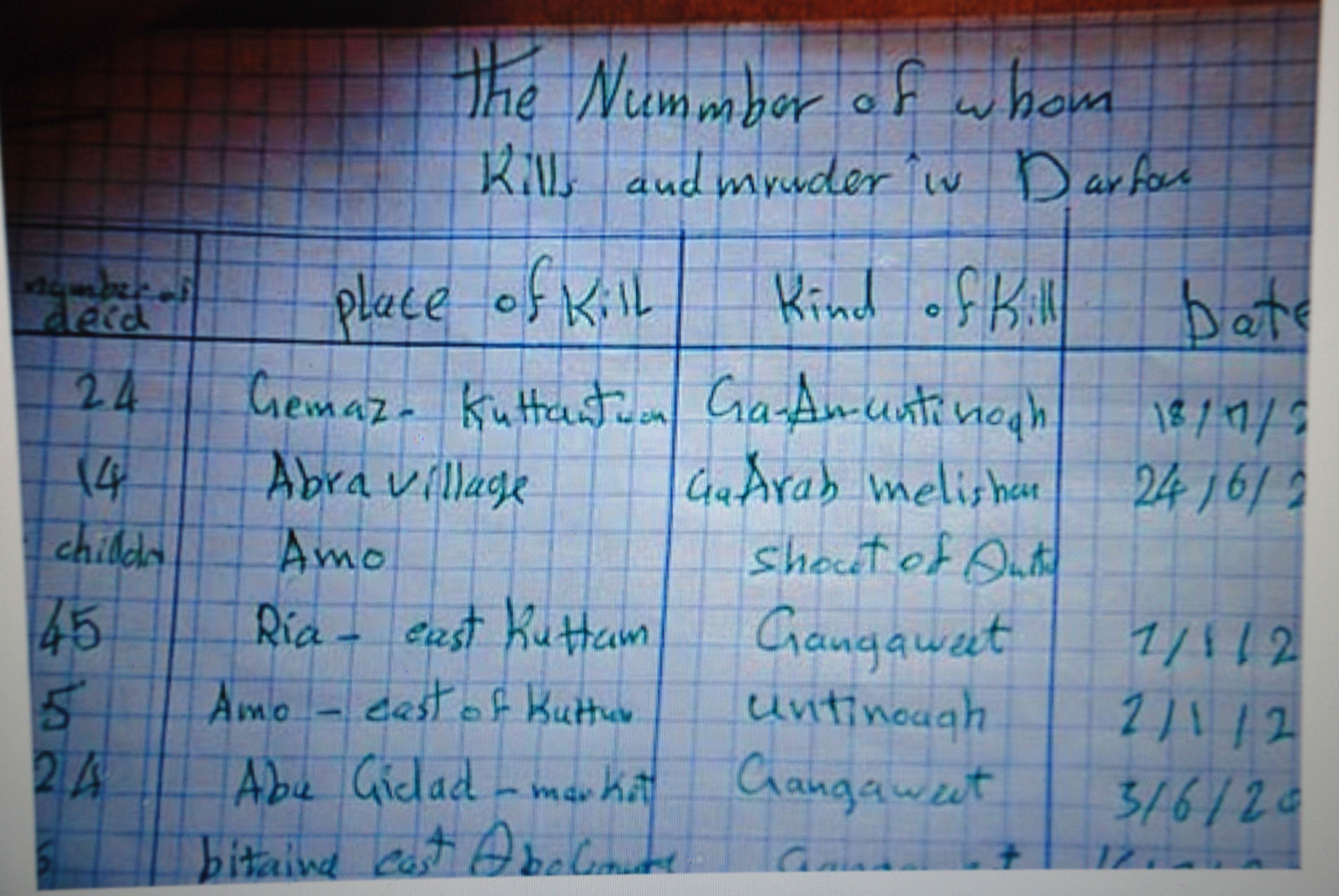

Darfuri refugees try to reconstruct mortality they witnessed in Darfur, with any details possible

Even so, we may be sure that excess global mortality is clearly many times what I predicted in 2004, and a great deal higher than the UN figure of 300,000 promulgated six years ago. And the dying continues, the victims vastly disproportionately African. The displaced and the refugees are also overwhelmingly from African tribal groups. Those who have lost their lands, their families, their homes, their way of life: these, too, are overwhelming from the African populations. In the end the debate about whether all this was, or is, genocide has come to seem pointless. People of particular ethnicity and tribal affiliation are targeted and killed on that basis. The ambition was to “change the demography” of Darfur and “empty it of African tribes.” That ambition has been realized. We should recall here that human displacement, the large-scale emptying of civilians in the extremely difficult climate of Darfur, is often tantamount to a death sentence. Only self-reporting by Darfuris allows us to estimate this population, if all too crudely. But we cannot pretend that such human destructive has been and continues to be anything other than massive. And of course the families and villages that perished in their entirety have no reporting presence anywhere.

Rape, denial of humanitarian access, appropriation of land and livelihoods, murder, deadly displacement, the intimidation UN peacekeeping efforts, and relentless, indiscriminate aerial bombardment of purely civilian targets are quite various means; but however chaotically, they serve the same end. And knowing this, and having been chosen, I can’t give up on the people of Sudan; I will not acquiesce before Khartoum’s genocidal ambitions. There is a grim and wearying familiarity to this work, as well as my work to highlight genocide in the Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile states—again three years in the making with the potential for massive human destruction. In May 2011—after months of arduous and painstaking work, and considerable research assistance—I published a monograph on Khartoum’s most savagely continuous method of war: indiscriminate bombing of civilians and humanitarians (“They Bombed Everything that Moved”: Aerial military attacks on civilians and humanitarians in Sudan, 1999 – 2011). No one had previously attempted to collate the vast data on such attacks, from a wide range of sources, even as the number of confirmed aerial attacks on civilians and humanitarians is now measured in the thousands. This is without precedent or comparable barbarism in the history of aerial warfare, Syria notwithstanding.

Since 1989, the Antonov cargo plane, retrofitted as a “bomber,” has been the direct source of many thousand of civilian deaths, and indirectly—by means of destroying agricultural production and generating mass flight by civilians—hundreds of thousands.

And South Sudan, to which my first five years were largely devoted, has become a source of unending heartbreak as the young nation continues to tear itself apart in vicious ethnic violence growing out of a political dispute (December 2013) that should have been forestalled long ago. I write relatively little on South Sudan now—mainly to highlight the impending famine, and culpability where it can clearly be assigned. The forces of violence have been too fully loosed, and there is no sign of diplomatic progress or sufficient humanitarian resources to avert famine. I contemplate contemporary South Sudan with the deepest and most painful anguish.

I have tried here to write something autobiographical, but in the end I find it impossible to talk about myself, only of what I’ve written and what continues to define the lives of millions of people in greater Sudan. My own life seems distinctly uninteresting, marked by a ceaseless exertion of the same energies, confronting the same distant suffering, with no change for the better that I might point to. My medical fate has remained precarious throughout the past ten years, with many difficult challenges, and several brushes with mortality. Chronicling my own problems, however, would seem to have a ghastly inappropriateness, given the suffering and destruction in Sudan. I have come as close to fatalism as my spirit allows me, and this means that—as I have all along—I write about the moment, what is occurring now, providing as much background as I dare (many of my analyses run to as many as 10,000 words, and most are in the range of 5,000 words).

The Sudan Tribune publishes a great deal of what I write, as do other Sudanese websites. I’ve also had a good deal of my work translated into Arabic at the urging of Sudanese friends, gaining a further audience. I’ve published some twenty pieces in The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, and The Wall Street Journal—many scores more on-line in Dissent Magazine, The New Republic, and The Guardian. Yet more work has appeared in other venues, including academic journals and collections of scholarly essays on Sudan. But aside from the success of the early divestment campaign directed against Talisman Energy, as well as my part in the success of using China’s hosting of the 2008 Summer Olympics as a means of highlighting Beijing’s complicity in Darfur’s genocide, I’m not sure that I have done anything but shout into a void of indifference. There are many exceptions, of course, many people who care deeply about greater Sudan and work hard to effect changes for the better. As I’ve said earlier, I have a great many dear friends in the worldwide community of Sudanese and friends of Sudan. But at present emergency humanitarian relief seems the only arena in which there are opportunities for success, and that success is highly limited—and in Darfur is diminished daily by a dysfunctional United Nations presence.

I now know all too well why the Greeks considered Cassandra’s gift of foresight a curse—for part of the curse was that nobody would believe her. But even so, I will continue to work to forestall what I see as growing catastrophe. I will, if nothing else, attempt to leave an archival record of all that the world chose to ignore of human suffering and destruction in greater Sudan. I am convinced that history, if not the present feckless international community, will judge these years more fully because of what I have written. Without at least this much to believe in I could not write at all.

September 2014

[Over the years there have been a number of profiles of my work, some more successful than others; they may be found at: http://sudanreeves.org/category/profiles-of-eric-reeves-work/]